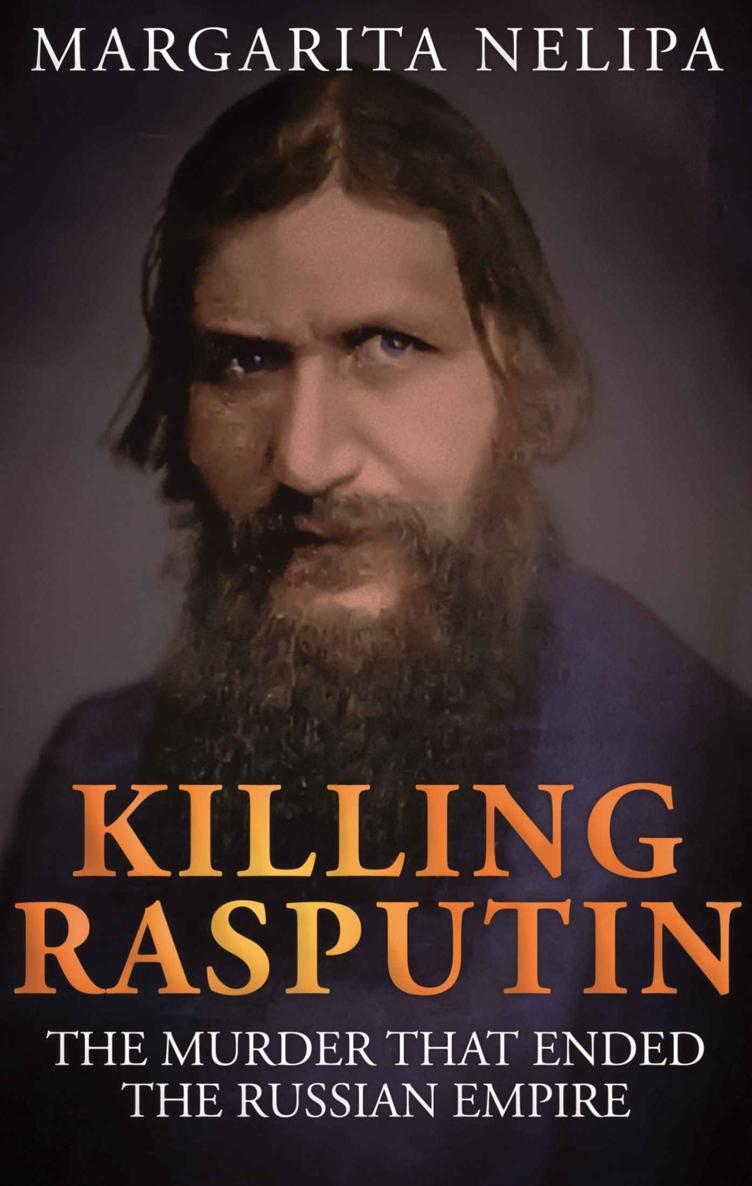

KILLING RASPUTIN

The Murder That Ended

The Russian Empire

Margarita Nelipa

KILLING RASPUTIN published by:

WILDBLUE PRESS

P.O. Box 102440

Denver, Colorado 80250

Publisher Disclaimer: Any opinions, statements of fact or fiction, descriptions, dialogue, and citations found in this book were provided by the author, and are solely those of the author. The publisher makes no claim as to their veracity or accuracy, and assumes no liability for the content.

Copyright 2017 by Margarita Nelipa

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of the Publisher, excepting brief quotes used in reviews.

WILDBLUE PRESS is registered at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Offices.

ISBN 978-1-942266-68-6 Trade Paperback

ISBN 978-1-942266-65-5 eBook

Interior Formatting/Book Cover Design by Elijah Toten

www.totencreative.com

Table of Contents

Notes on Sources

My disbelief that a British secret agent was implicated in murdering Grigorii Rasputin gave me the determination to study all the original material related to this murder case, then test that disclosure against the book To Kill Rasputin .

Prior to 1924, a few publications appeared in print before the Soviet censors sealed access to its archives. The first book published on the subject of Rasputins murder was the purported diary penned by Vladimir Purishkevich, who took part in Rasputins murder. His book appeared in 1918 in Kiev during the Civil War in Southern Russia. During 1917, when the Provisional Government was in power, material that had been previously subject to censorship was published. Parts of the secret investigation that was conducted by the District Court and the gendarmes appeared in the journal Byloye ( Past Times ). Other associated material was published in special issue booklets, newspapers Russkaya Volya ( Russian Will ), Rech ( Speech ), and Birzheviye Vedomosti ( Stock Exchange Record ), to mention just a few.

Alexander Blok (poet and lawyer) wrote the second book. That publication, of which pertinent details appear in this book, refuted all accusations construed against Grigorii Rasputin.

After the Bolsheviks came to power, the Commission of Inquirys work ceased; the effect of any valuable information that might have been brought before the panel was silenced. In the same way, Rudnevs published conclusions did not accord with the Bolshevik political objectives, which meant his expos was suppressed in the Soviet Union. After Vladimir Lenin died in January 1924, access to all government archives and libraries was curtailed. That action ensured that private research stopped. As a result, any major studies relating to Rasputin and the imperial era appeared abroad in cities where migrs had relocated. Those migr authors may be categorized as being either favorable, uncommitted, or antagonists of Rasputin and the imperial regime. On the other hand, because they offered diverse impressions about Rasputins character and what conditions might have led to his murder, their publications, with their intrinsic biases, added to the complexity of evaluating the truth about the historic and forensic questions concerning Rasputins murder.

Before the Soviet government tightened control over its archives, it published multi-volume compendiums, titled Krasnii Arkhiv ( The Red Archives ) from 1922 until 1941, as well as Padeniye Tsarskogo Regima ( The Fall of the Tsarist Regime ) from 1924 through 1927. Though the first series uncovered a collection of letters written by Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich in 1928, few Soviet historians had the opportunity to conduct independent research regarding the Delo Rasputina ( The Rasputin Case ).

To maintain government control, all proposed publications required approval by its censors, who themselves were monitored by a network of security agencies such as the NKVD and its later identity, the KGB. Excluding the series of Soviet encyclopedias and occasional journal articles that touched on Rasputins death, only a few biographic books saw the light of day towards the end of the Soviet era. One such example was Mark Kasvinovs Dvadtsat tri Stupeni Vniz, a 1989 book whose title translates as Twenty-three Steps Down .political objective.

With the collapse of the Soviet government and easing of political censorship, Russian playwright and historian Edvard Radzinsky became one of the first who was able to examine the concealed archival documents concerning Nikolai II and his reign. Radzinskys account of the imperial familys murder appeared in 1992. Radzinsky noted that Grigorii Rasputins autopsy report was held in the archives until the 1930s, but during his search, that document was missing. During the early 1990s, a journal maintained by Rasputin (more akin to personal reflections than a diary of events) was found in the archives of the former Senate and Synodal building. Much later, Radzinsky discovered a folder at the Political History Museum (located in the former residence of the imperial ballerina Mathilde Kschessinskaya). It was labelled Delo Rasputina , Case No. 573, and titled Sledstviye po delu ob Ischeznovenii Grigoriya Efimovicha Rasputina (Investigation in the matter of the disappearance of Grigorii Efimovich Rasputin). That folder contained police photographs taken during the secret investigation conducted during Nikolai IIs reign. The sight of those images piqued Radzinskys interest to continue his research into Rasputins life and death in an attempt to understand some truths that have eluded historians.

Radzinsky also gained permission to access the Yusupov family archive that, at the time, was held at the Political History Museum. It contained correspondence between Felix Yusupov and his mother, Zinaida, as well as letters Felix had written to his wife Irina. That correspondence revealed how the plot to murder Rasputin had developed and also exposed the socialites loathing for Rasputin. During his visit to Paris, Radzinsky met Mstislav Rostropovich (the famous cellist and conductor), who, as agreed earlier in Moscow, handed him a folder. The folder contained original documents amounting to five hundred pages from the 1917 Extraordinary Commission of Inquiry. The papers were hand-signed by those who had submitted their testimonies before the presiding commissioner, Nikolai Muravyev. Returning the file to Russia, Radzinsky (and Rostropovich) ensured it was placed with the corresponding files already held in the Russian State Archives in Moscow. Radzinskys efforts saw the release of his second book The Rasputin File in Russia and abroad during 2000.

Other writers showed interest in Rasputin. Ivan Nazhivin, who died in 1940, published his narrative about Rasputin in 1923 in Berlin, and was only made available in Russia in 1995. even though a translation had appeared in France during 1982.

Then in 1990, the Soviets allowed the publication of a book titled Svyatoi Chert ( Holy Devil ) that contained a few testimonies sourced from the 1917 Extraordinary Commission of Inquiry. Once the communist regime dissolved in 1991, Russian historians, using their newly found political freedom, sought out their archives. One significant finding came to light after Artur Chernyshov gained permission in 1991 to search through the Tyumen District State Archives (GATO). He found the records from the Bogoroditskoi Church in Pokrovskoye village, the birthplace of Grigorii Rasputin. That register contained the register of births, deaths, and marriages of the Rasputin family. Chernyshev published some of those pages in 1992, revealing Rasputins date of birth. In 2016, I accessed the same register from GATO and am the first person in the West to provide photographic evidence of Rasputins birth particulars.