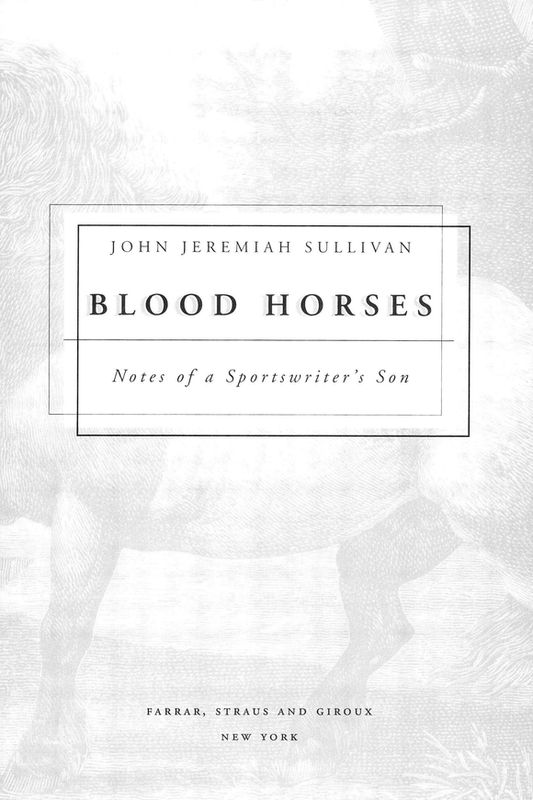

It was in the month of May, three years ago, by a hospital bed in Columbus, Ohio, where my father was recovering from what was supposed to have been a quintuple bypass operation but became, on the surgeons actually seeing the heart, a sextuple. His face, my fathers face, was pale. He was thinner than I had seen him in years. A stuffed bear that the nurses had loaned him lay crooked in his lap; they told him to hug it whenever he stood or sat down, to keep the stitches in his chest from tearing. I complimented him on the bear when I walked in, and he gave me one of his looks, dropping his jaw and crossing his eyes as he rolled them back in their sockets. It was a look he assumed in all kinds of situations but that always meant the same thing: Can you believe this?

Riverside Methodist Hospital (the river being the Olentangy): my family had a tidy little history there, or at least my father and I had one. It was to Riverside that I had been rushed from a Little League football game when I was twelve, both of my lower right leg bones broken at the shin in such a way that when the whistle was blown and I sat up on the field, after my first time carrying the ball all season, I looked down to find my toes pointing a perfect 180 degrees from the direction they should have been pointing in, at which sight I went into mild shock on the grass at the fifty-yard line and lay back to admire the clouds. Only the referees face obstructed my view. He kept saying, Watch your language, son, which seemed comical, since as far as I knew I had not said a word.

I seem to remember, or may have deduced, that my father walked in slowly from the sidelines then with the exceptionally calm demeanor he showed during emergencies, and put his hand on my arm, and said something encouraging, doubtless a little shocked himself at the disposition of my foota little regretful too, it could be, since he, a professional sportswriter who had been a superb all-around athlete into his twenties and a Little League coach at various times, must have known that I should never have been on the field at all. Running back was the only viable position for me, in fact, given that when the coach had tried me at other places on the line, I had tended nonetheless to move away from the other players. My lone resource was my speed; I still had a prepubescent track runners build and was the fastest player on the team. The coach had noticed that I tended to win the sprints and thought he saw an opportunity. But what both of us failed to understand was that a running back must not only outrun the guardstypically an option on only the most flawlessly executed playsbut often force his way past them, knock them aside. Such was never going to happen.

In fairness, the coach had many other things to worry about. Our team, which had no name, lacked both talent and what he called go. In the car headed home from our first two games, I could tell by the way my father avoided all mention of what had taken place on the field that we were patheticnot Bad News Bears pathetic, for we never cut up or wanted it or gave our all. At practice a lot of the other players displayed an indifference to the coachs advice that suggested they might have been there on community service.

The coachs son, Kyle, was our starting quarterback. When practice was not going Kyles way, that is, when he was either not on the field, having been taken off in favor of the second-stringer, who was excellent, or when he was on the field and throwing poorly, Kyle would begin to cry. He cried not childish tears, which might have made me wonder about his life at home with the coach and even feel for him a little, but bitter tears, too bitter by far for a twelve-year-old. Kyle would then do a singular thing: he would fling down his helmet and run, about forty yards, to the coachs car, a beige Cadillac El Dorado, which was always parked in the adjacent soccer field. He would get into the car, start the engine, roll down all four windows, andstill crying, I presumed, maybe even sobbing now in the privacy of his fathers automobileplay Aerosmith tapes at volumes beyond what the El Dorados system was designed to sustain. The speakers made crunching sounds. The coach would put up a show of ignoring these antics for five or ten minutes, shouting more loudly at us, as if to imply that such things happened in the sport of football. But before long Kyle, exasperated, would resort to the horn, first honking it and then holding it down. Then he would hold his fist out the drivers-side window, middle finger extended. The coach would leave at that point and walk, very slowly, to the car. While the rest of us stood on the field, he and Kyle would talk. Soon the engine would go silent. When the two of them returned, practice resumed, with Kyle at quarterback.

None of this seemed remarkable to me at the time. We were new to Columbus, having just moved there from Louisville (our house had been right across the river, in the knobs above New Albany, Indiana), and I needed friends. So I watched it all happen with a kind of dumb, animal acceptance, sensing that it could come to no good. And suddenly it was that final Saturday, and Kyle had given me the ball, and something very brief and violent had happened, and I was watching a tall, brawny man-child bolt up and away from my body, as though he had woken up next to a rattlesnake. I can still see his eyes as they took in my leg. He was black, and he had an afro that sprung outward when he ripped off his helmet. He looked genuinely confused about how easily I had broken. As the paramedics were loading me onto the stretcher, he came over and said he was sorry.

At Riverside they set my leg wrong. An X ray taken two weeks later revealed that I would walk with a limp for the rest of my life if the leg were not rebroken and reset. For this I was sent to a doctor named Moyer, a specialist whom other hospitals would fly in to sew farmers hands back on, that sort of thing. He was kind and reassuring. But for reasons I have never been able to fit back together, I was not put all the way under for the resetting procedure. They gave me shots of a tranquilizer, a fairly weak one, to judge by how acutely conscious I was when Dr. Moyer gripped my calf with one hand and my heel with the other and said, John, the bones have already started to knit back together a little bit, so this is probably going to hurt. My father was outside smoking in the parking lot at that moment, and said later he could hear my screams quite clearly. That was my first month in Ohio.

Two years after the injury had healed, I was upstairs in my bedroom at our house on the northwest side of Columbus when I heard a single, fading Oh! from the first-floor hallway. My father and I were the only ones home at the time, and I took the staircase in a bound, terrified. Turning the corner, I almost tripped over his head. He was on his back on the floor, unconscious, stretched out halfway into the hall, his feet and legs extending into the bathroom. Blood was everywhere, but although I felt all over his head I couldnt find a source. I got him onto his feet and onto the couch and called the paramedics, who poked at him and said that his blood pressure was all over the place. So they manhandled him onto a stretcher and took him to Riverside.

It turned out that he had simply passed out while pissing, something, we were told, that happens to men in their forties (he was at the time forty-five). The blood had all gushed from his nose, which he had smashed against the sink while falling. Still, the incident scared him enough to make him try again to quit smokingto make him want to quit, anyway, one of countless doomed resolutions.