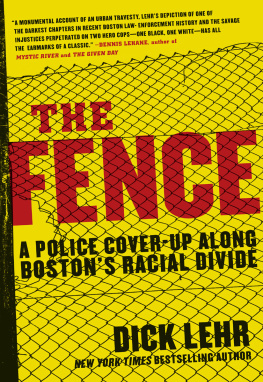

Contents

January 25, 1995

Two Cops and a Drug Dealer

Mike Cox

Robert Smut Brown

Kenny Conley

The Troubled Boston PD

Mikes Early Police Career

Closing Time at the Cortees

The Murder and the Chase

The Dead End

True Blue

8-Boy

No Official Complaint

Can I Talk to My Lawyer?

Dave, I Know You Know Something

Cox v. Boston Police Department

Justice Denied, Then the Trial

The White Guy at the Fence

The Perjury Trap

A Federal Miscarriage of Justice

On His Own

The Trial

Court Cases

Books; Articles and Special Reports

Boston Police Department Rules and Regulations; Boston Police Department Internal Investigations; Boston Police Department Labor Arbitration Proceedings; Suffolk County District Attorneys Office; United States Attorneys Office, District of Massachusetts

January 25, 1995

W hen Kimberly Cox was awakened by the telephone ringing in the middle of the night, the fourth-year medical student had been sleeping hard. Shed slept through the Boston police and ambulance sirens blaring an hour earlier on Blue Hill Avenue two blocks from her home. She was likely used to the discordant sounds; the wail of sirens was not unfamiliar in Dorchester, where she and her family lived, one of the many black families making up the neighborhood.

When the phone rang, she was alone in bed. Her first thought was that her husband, Michael, was calling. Michael was usually home by 2 A.M .; if he was going to be later he would call. Then Kimberly noticed the clock: It read 3:30.

She picked up the receiver.

Mrs. Cox?

Kimberly did not recognize the voice.

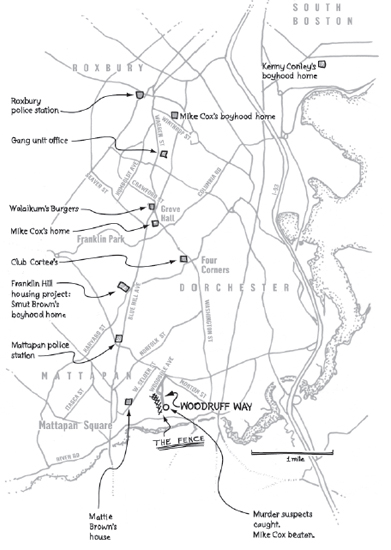

The caller identified himself as Joe Teahan, an officer with the Boston Police Department. Kimberly worked to clear her head. The name meant nothing to her. In fact, Teahan was a white officer who worked with her husband in the departments elite anti-gang unit, composed of officers working primarily in street clothes, who targeted the street gangs of Roxbury and Dorchester. The gang units supervisor had instructed Teahan to call Mikes wife. Just dont scare her, the sergeant had said.

Kimberly listened as the voice told her Mike had been in an accident.

What kind of accident?

Hes alive but hurt. Hes on his way to Boston City Hospital.

Kimberly was up and standing by the bed. She was nervous all over. She dressed quickly. Teahan said they would send a car to get her. But it wasnt that simple. Fast asleep in their bedrooms were her boys, six-year-old Mike Jr. and Nick, whose fifth birthday was still fresh on everyones mind. She told Teahan shed call him back after figuring out the logistics. She hung up and hurriedly dialed her mother-in-law. Kimberly was thinking Bertha Cox could stay with her sons. But when Bertha arrived a few minutes later, she insisted on going along with Kimberly to the hospital. This led to more telephone calls to other family members to ask them to hurry to 52 Supple Road, where Michael and Kimberly and their boys lived in the second-floor apartment of the two-family home owned by one of Michaels sisters.

It took nearly an hour for Kimberly to sort it all out. Thats when Joe Teahan and his partner, Gary Ryan, pulled up in front of the red-brick house. The two officers had first met as classmates in the police academy and had worked side-by-side for most of their four years on the force. They could see that fellow officer Mike Cox was living in the middle of it all. Walking a block in any direction landed you on a street where guns and drugs were the name of the game. In fact, for Mike and the dozen or so gang unit officers on a special operation that night, the trouble had begun only three blocks away.

Kimberly and Bertha Cox came down the brick front steps, hurried across the cement walkway of the tiny front yard, and climbed into the backseat of the cruiser. The two officers stuck to the script. They told Kimberly that Mike had head injuries. They said he likely slipped on a patch of ice, hit his head, and split it open pretty good. Gary Ryan did not share what hed thought when he first saw Mike on the ground, his head so bloodied and swollen, it looked like a gunshot wound. The sergeant had said not to alarm her. Little else was said during the short drive to the hospital about a mile away.

The two women were taken to the emergency room entrance. They rushed through a double set of automatic doors. The entry-ways linoleum floor was covered with a carpet rolled out in winter-time to absorb wet snow and slush. Nurses steered them through the trauma units two heavy wooden doors that swung outward.