CLIMBING IVY PRESS

Hingham, MA USA

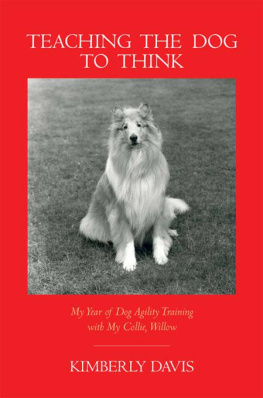

Copyright 2011 Kimberly Davis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission of the author.

ISBN-10: 0983449201

ISBN-13: 9780983449201

eBook ISBN: 978-0-9834492-3-2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011925010

Climbing Ivy Press, Hingham, MA

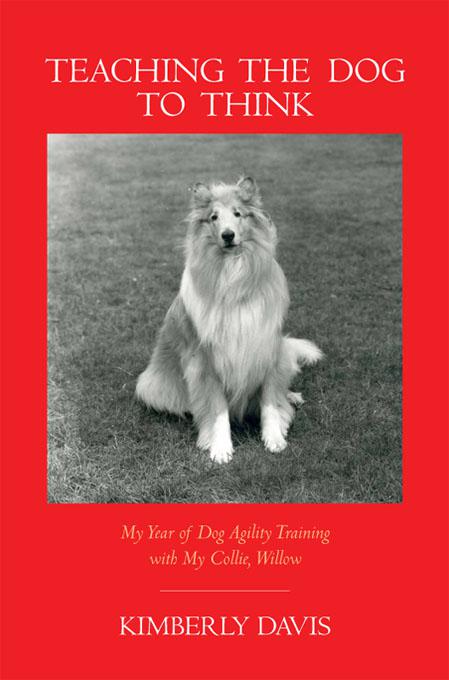

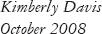

Front cover photograph used by permission of Jonathan Simmons.

Copyright 2000 Jonathan Simmons.

Author photograph used by permission of Trudy Tucker.

Copyright 2004 Trudy Tucker.

For permissions and reprints, please contact:

Climbing Ivy Press, P.O. Box 199, Hingham, MA 02043.

For Steve and Daniel

Contents

E ight years ago, when I began taking dog agility classes with my collie Willow, I had no idea that for a time agility training would come to take over my life. As far as I was concerned, I was just signing up for more obedience classes with the unruly family dog. During that period, I was on an extended hiatus from practicing law, a career I had left a few years earlier to care for my dying mother and my young son. My mother had recently passed on, though, and my son had reached an age where he was in school part of the day, leaving me suddenlyand for the first time in my adult lifewith free time on my hands, time that I used to pursue my MFA in creative writing and to take up dog agility. Little did I know that agility training would turn out to have a profound effect upon me. I am still working out in my own mind all that I took from the training. Certainly agility has dramatically changed the way I look at animals. When I started, I think that I viewed the family pets mainly as infantile creaturesas wayward simpletons I needed to boss and control in order to make them more docile, tractable, and pleasant to be around. No real interchange with them was required or even especially desirable. I now see the family petsand particularly my dogsvery differently. I understand them as fully matured and fledged individual personalities with their own needs and desiresdesires that we humans can harness to get more out of them than would ever be possible through the old forced training methods I used to use. But that is not the only thing that I took from agility. In addition to revealing things about the animals in my care, the training also showed me a great deal about myself, especially about my interpersonal relationships and how I conducted myself in the worldand particularly the shortcomings in the way I was parenting my son, Daniel. Through the training I gained valuable lessons about how to get others to do what you want, about teaching and learning and building skills, and about fostering creativity. I have, for the most part, disguised the identities of the agility trainers with whom Willow and I worked to protect their privacy, but they know who they are. To these talented teachers, I am deeply indebted. They have enriched my life and deepened my understanding of dogs and of humans in more ways than I can count. My hope is that this little book will serve as something of a valentine to these calm, sane, and remarkable people from whom I have learned so much.

|

Motivation is the art of getting people to do what

you want them to do because they want to do it.

Dwight D. Eisenhower

T his story has its beginning on an evening in mid-September, 2000. I had arrived with my dog just before dark at the equestrian arena in Plymouth, Massachusetts, where our first agility class would be held. Not yet aware that there was parking behind the arena, I had left our car up by the road, and we now made our way on foot down the long sloping gravel drive toward the big blue dome-shaped building. At the time, I had very little information about agility. I knew only that it was the newest rage in dog sports in the United States, and that it involved a course of varying obstacles through which the dogs raced, performing jumps, tunnels, seesaws, and balance beams. Years later, as I write this, you can catch at least a glimpse of agility nearly any night on Animal Planet, but at the time we began our training I had only read about this burgeoning sport of dog antics in magazines, and seen a demonstration or two at dog shows. It looked like fun to me, and having already done a little obedience training, I had decided to give it a try with my yearling collie, Willow.

And so we crunched down the long gravel driveway, my dog and me, through the gathering dusk to the arena. It was, as I recall, still summer warm that evening, tiny insects raining upon my bare arms, and the fading light growing misty over scrubby pines. We were not far from the ocean, and the air smelled strongly of salt. As we walked, Willow strained at the end of his taut webbed leash, his neck clicking the links of his choke collar and his nose twitching with the musky, exciting scent of hot horse on the hoof. I had gotten this dog as a puppy from a highly recommended breeder in Danbury, Connecticut, and dancing this way at the end of his lead he lookedat the timeevery bit the specimen of a lovely purebred collie.

Now when I say that Willow was (and is) a purebred collie, I dont mean the picture thatafter some recent childrens moviesvaults to a lot of peoples minds: of a small nervous piebald dog crouched before a bunch of sheep, riveting them with his gaze. That would be the border collie. That is not Willow. Willow is what people used to think of as a collie back in the glory days of Hollywood when the word meant Lassie and Lad and other such leggy, blond canines. Willow is what these days is called a rough collie, and he is firmly in that Lassie Come Home line. He was thenand though older, remains todaya tall, elegant, golden dog with a deep white chest and tiny almond-shaped eyes set into a long flat head. With slightly crossed eyes, you might think, were you to look at him straight on, for he has that highly bred cast of British royalty. But he was, and is, handsome anywayand back then he was extremely pleasing to look at, especially in motionwith his high-stepping show-ring gait. He was that night, in short, a gorgeous exemplar of his kind. He was everything that the American Kennel Club might have dreamed up for a young purebred collie. But at a year old, he was also a boisterous youngster, and deeply unruly despite months of Puppy Kindergarten classes. And he had always wanted to chase and bring down a full-sized horse. He just never knew it until that moment when he actually saw one for the first time.

A big caramel-colored thoroughbred had come sidestepping out of the mouth of the arena and directly across the gravel path in front of us. Willows reaction was immediate and enthusiastic. He reared back on his hind legs and lunged forward at the skittish equine, exerting maximum pressure on his choke collar and leash, and nearly yanking me off my feet. I am a small, book-oriented woman, and even with the choke collar he and I were nearly an even match. In the same moment as he jerked forward, Willow also gathered into that deep white chest of his a great gasp of air that was released as shrill, rapid-fire barking ending in something resembling a howl as the choke collar throttled his windpipe with a zipping noise. Struggling to reassert my authority over my hysterical charge, while not actually strangling him, I grasped my hand through the flat, webbed collar he also wore, and snapped the leash onto this kinder restraint from which his dog tags swung like a necklace. Willow bounced on his forepaws, still barking shrilly at the horse, but I had him now, and I led him firmly by the collar around the corner of the building and into the corrugated-aluminum arena.

Next page