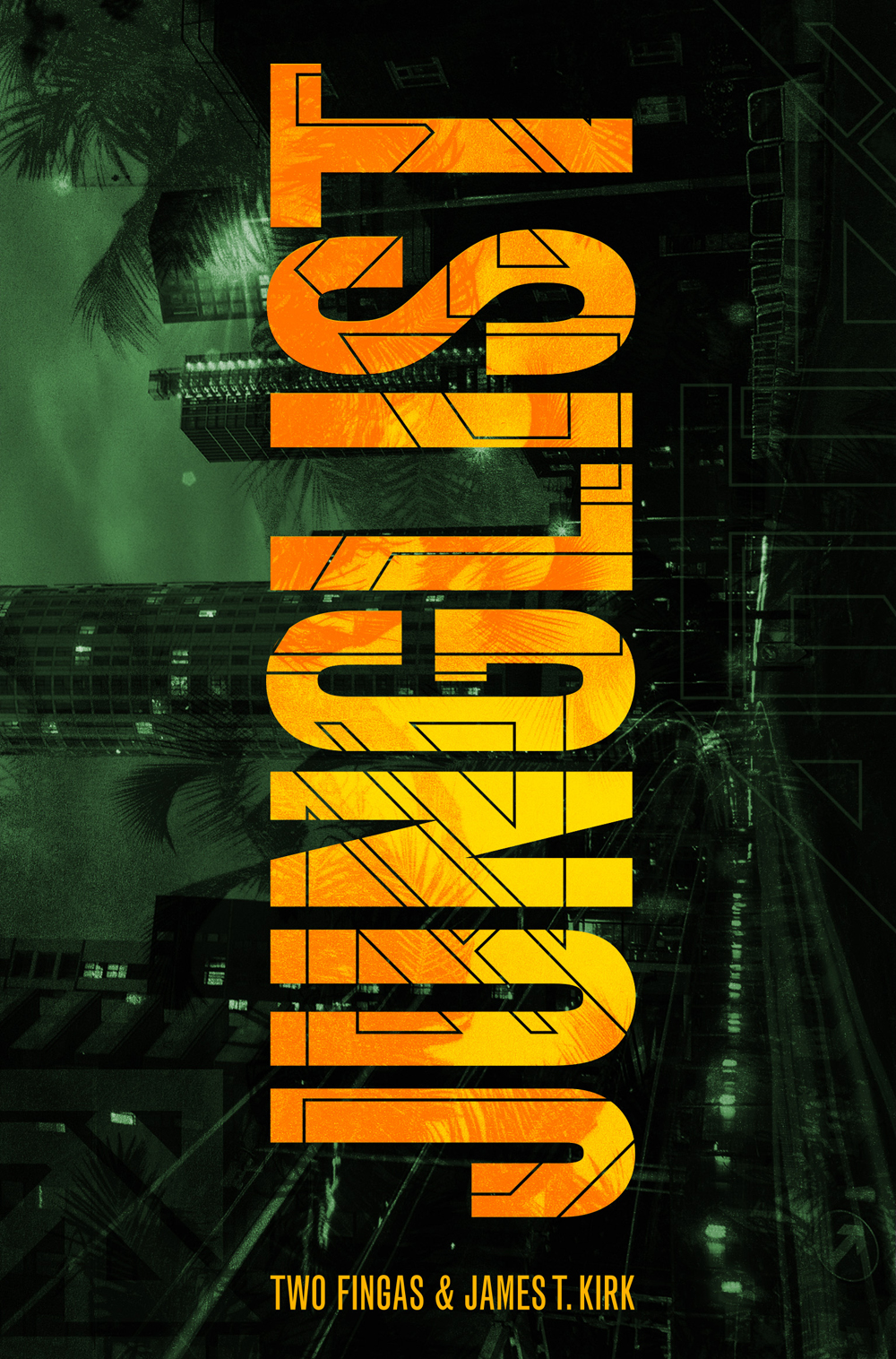

Two Fingas James T. Kirk - Junglist

Here you can read online Two Fingas James T. Kirk - Junglist full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Repeater Books, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Junglist

- Author:

- Publisher:Repeater Books

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Junglist: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Junglist" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Junglist — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Junglist" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Published by Repeater Books

An imprint of Watkins Media Ltd

Unit 11 Shepperton House

89-93 Shepperton Road

London

N1 3DF

United Kingdom

www.repeaterbooks.com

A Repeater Books paperback original 2021

Distributed in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York.

Copyright Andrew Green & Eddie Otchere 2021

Andrew Green & Eddie Otchere assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work.

Introduction copyright Sukhdev Sandhu 2021

Typesetting and design: Frederik Jehle

Front cover design: ptplondon.com

ISBN: 9781913462505

Ebook ISBN: 9781913462512

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

CONTENTS

BY SUKHDEV SANDHU

INTRODUCTION: THE INTENSE NOW

You could see it in people, you could see it in their eyes. Those ravers were at the edge at their lives, they werent running ahead or falling behind, they were just right there and the tunes meant everything. Burial

Andrew Green and Eddie Otchere (aka Two Fingas and James T. Kirk) came of age at a strange, indeterminate time. It was the early 1990s, post-Thatcher and post-Berlin Wall a period of fudge and inertia, of recession and housing market collapse, of Britain being forced to leave the European Exchange Rate Mechanism. The Greater London Council had been abolished in 1986 and the city still had no mayor. Tourists were in short supply; bombs the IRA attacked the Baltic Exchange, Bishopsgate, even Downing Street were not.

Green and Otchere were from council estates south of the Thames in Vauxhall. The MI5 building had yet to go up in the neighbourhood and it was hard to imagine that the US embassy would one day move there. Where they lived squatters were common. The fires that often broke out would have caused even more devastation than they did if the highrise walling wasnt so stuffed with asbestos. Turning sixteen, the two teenagers, both creative and independently minded, headed across town to Hammersmith and West London College. There they bonded over a shared love of comics, basketball, kung-fu movies. Music too.

Green had been a hip-hop and happy hardcore fan. Increasingly he was getting into Jungle. He viewed the club nights he attended as extensions of the house parties of his youth: front rooms cleared of all furniture, huge sound systems, alcohol served in plastic cups, dim lighting, lots of motion. He found Jungle intimate and immersive a sometimes demonized music to which young kids, in darkened spaces the size of chill-out zones, were still figuring out how to dance. It was a music that was impossibly accelerationist. Its rhythms thrillingly alien. Its darkness radiant.

Otchere, a photographer with a keen eye for social semiotics, had noticed that the white racist kids that I went to school with came back from their summer holidays not racist anymore. I was trying to figure out what the fuck happened. Jungle offered a partial answer:

The rave culture we as Black kids in south London started to experience in the Nineties began four years earlier with those white kids. We saw how much fun they were having and brought it into our own circles. By just dancing together, by mimicking each others body movements, by being under the same roof, listening to the same music, feeling the same high, taking the same pills: in that magic moment the moodiness was gone.

Jungle had its own subaltern economy. White-label 12-inch records were produced on the cheap, pressed up by tiny independents, spun at clubs and by pirates, sometimes sold from the boots of cars. Cash in hand. Not a word to the taxman. DIY creativity at its most kinetic and entrepreneurial. Some of that energy was channelled into publishing. Deadmeat, a novel about a Black cyber-vigilante stalking the streets of London, was initially sold at clubs by its author Q. Better known is The X-Press, an imprint set up by Dotun Adebayo and Steve Pope in 1992, which published Victor Headleys Yardie and Donald Gorgons Cop Killer. These books were often accused of glorifying violence and of being no-brow trash, but their hefty sales were hard to ignore.

One individual paying particular attention was Jake Lingwood, a twenty-something editor at Allen and Unwin. He had a passion for mod and, as a teenager, had started the zine Smarter Than U, which he named after a song on the Undertones 1978 Teenage Kicks EP. Excited by the energy of the London club scene, he decided to commission a series of novel-length documentations that would allow outsiders to peek into social worlds they might otherwise have felt too intimidated to actually visit or join. He named it Backstreets, and was soon casting about for writers prepared to bash out vaguely workable prose in a couple of months and for an advance of a few thousand pounds.

By this time, Green and Otchere had figured out, as canny youngsters tend to, that the best way to get free records and tickets swag was by writing for magazines. They were penning film reviews for Black lifestyle journal Touch; Otchere was also taking photos for it and had contributed cover images for X-Press titles. Hed even shot something for one of the first Backstreets novels. If in retrospect it seems obvious that Lingwood would ask him to write a drum n bass-themed volume and that he would ring his friend to suggest they collaborate on it initially there were some tricky issues to resolve. Neither of them were particularly interested in literary fiction (a term I despise, says Green today); the word-length was 50,000 (about 48,000 longer than anything either of them had ever written before); Green was now up country studying film at Northumbria University. Otchere says hed never even read a full-length novel up to that point, preferring instead the wordplay and poetry of the sleevenotes on Sun Ra LPs.

Still, they said yes. Green remembers thinking, Fuck it, why not? I was eighteen or nineteen full of young person confidence. He had felt a weird sense of dislocation in Newcastle; writing about London was a chance to take stock of his upbringing and the music that had rewired him. The book would be a quota-quickie like youthsploitation novels such as Wolf Mankowitzs Expresso Bongo (1958) and Richard Allens Skinhead (1970) (the latter a key reference point for Lingwood), but also like those pulp fictions historically churned out by the comic and science-fiction writers Green adored. He could stay anonymous like a graffer or an underground producer issuing multiple releases under different pseudonyms. He and Otchere could even use the excuse of writing it as a way to get on guestlists and jump the queues at otherwise rammed clubs. Research!

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Junglist»

Look at similar books to Junglist. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Junglist and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.