Contents

Guide

First published by Pitch Publishing, 2020

Pitch Publishing

A2 Yeoman Gate

Yeoman Way

Durrington

BN13 3QZ

www.pitchpublishing.co.uk

Stephen ODonnell, 2020

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the Publisher.

A CIP catalogue record is available for this book from the British Library

Print ISBN 978 1 78531 643 2

eBook ISBN 978 1 78531 734 7

--

Ebook Conversion by www.eBookPartnership.com

Contents

Acknowledgements

T HE author would like to thank the following people for their help during the writing of this book: Tom Boyd, Colm Clancy, Gregor Clark, David Faulds, Tom Grant, Sandy Jamieson, David Kelly, Steve Fitzpatrick and friends, Matthew Leslie, Richard McGinley, Matt McGlone, Ally Palmer, David Potter, Andy Ross, Brendan Sweeney and Alf Young. Additional thanks to the staff of the Mitchell Library in Glasgow and the National Library of Scotland in Edinburgh, and to everyone at Pitch Publishing, especially Jane Camillin. Writing is a solitary activity but a book is always a combined effort, so thanks again guys.

Foreword

A GENERATION ago, British football clubs were British owned. Owners tended to be local butchers, bakers and candlestick makers. Turnstile income was all that mattered and the larger the population of the town, the bigger the club tended to be. Banks didnt lend to football clubs and, consequently, everyone lived within their means.

All of that changed in the 1980s following the elections of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. Both promoted deregulation of financial markets, cultures of easy money and increased corporate activity.

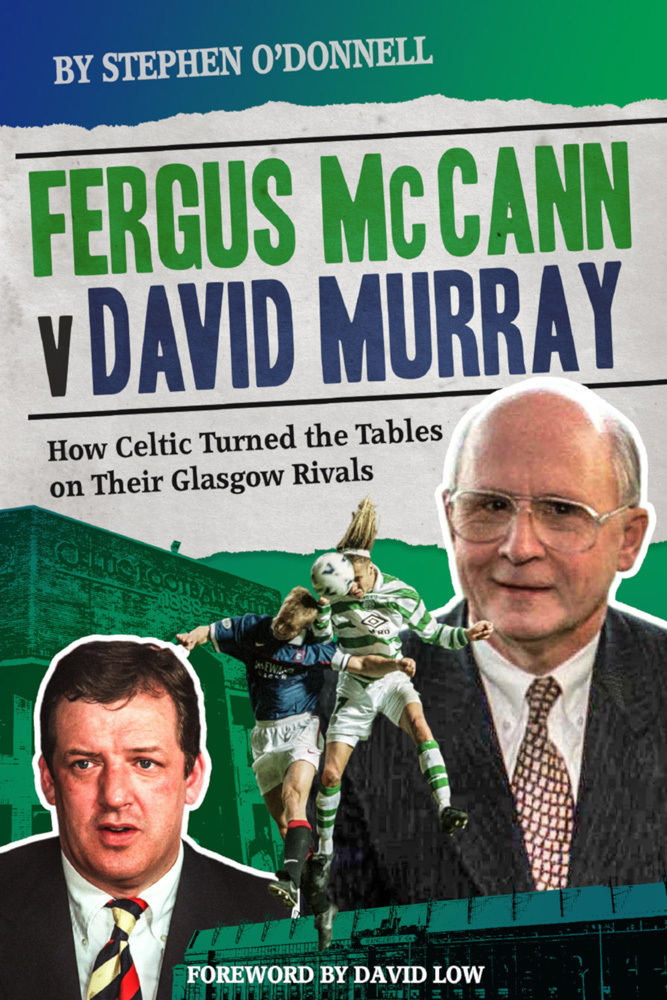

Football clubs started to change hands, and in 1988 David Murray acquired a controlling interest in the old Rangers, which valued the clubs share capital and bank debt at 12.5m. The clubs new parent company, Murray International, was already carrying bank debt of circa 40m, meaning the whole Rangers enterprise was entirely dependent on bank borrowing from the outset and well before it was liquidated 20-odd years later.

Across the city at Celtic, the financial climate change passed unnoticed until it was almost too late. The directors lacked vision, commercial acumen and money, and were eventually forced out after a two-year war of attrition with shareholders and supporters. Fergus McCann arrived and acquired a controlling interest in a deal that valued the club at 13.5m before the share issue to supporters at the end of 1994.

In late 1992, I had flown to Montreal to meet Fergus McCann. The purpose was to try to persuade him to back my plan for removing the Celtic board and to support a substantial capital investment. In his apartment his first words to me were, Hello, Mr Low, who are you, why are you here, and what do you want? I loved that, straight to the point, no bullshit and a characteristic that was not always appreciated during his time in Scotland.

Fergus had always been adamant that any investment he made would go straight to Celtic and that he was not prepared to buy shares from the outgoing directors, given their mismanagement of the clubs affairs. However, on 4 March 1994 he was confronted with that very dilemma; the old board had no choice but to surrender their positions if the club was to avoid receivership, but the change in control would not take place without acquiring their shares. Protracted negotiations ensued over the course of the day and Fergus eventually agreed to set aside some money to buy the directors shares. It was the only time I can recall getting him to change his mind about anything. That deal sealed the change in control. It was a momentous day in Celtics history. The game was over and the rebels had won!

This book deals with two contrasting styles of personality and management: Rangers under the control of the risk-taking and bank-financed David Murray, always living on the edge and pitted against Celtic, now controlled by Fergus McCann, and with a business plan that promoted financial stability, steady improvement and operating within its means.

The Murray model was always going to be popular with fans, as it appeared to provide limitless amounts of money to buy better players, greater football success and never-ending football domination over their oldest rivals. McCanns plan was more difficult to implement and required focus, discipline and patience.

Rangers dominated the 1990s and won nine league titles in a row. Celtic supporters, manipulated by a Rangers-leaning media, became increasingly agitated at the Celtic boards refusal to pursue the risky buy now, pay later policy of their rivals. Despite this, and against the financial odds, Celtic managed to win the league and prevent Rangers from winning its coveted tenth league title in a row. However, that didnt stop a section of the Celtic support booing McCann when he unfurled the league championship flag at the start of the following season.

The other major and often overlooked difference between the two clubs was in the calibre of experience of their boards of directors. Unlike Rangers, Celtic was listed on the London Stock Exchange and had a board of directors that understood the importance of good governance and sound financial practice. These characteristics were important in providing the continuity of management needed after McCanns departure in 1999. McCanns real legacy was a management structure and ownership profile that provided continuity of philosophy to this day.

Under Murray, Rangers fared less well. During his ownership, the Bank of Scotland continued to lend his companies seemingly endless amounts of money, but all that stopped with the financial crash in 2008 and the takeover of Halifax Bank of Scotland by Lloyds TSB the same year. The lending stopped and the club had to start downsizing and paying off bank debt. The whole debt orgy had lasted an exceptional 20 years. Financial profligacy and greed had dominated the sporting landscape, distorted on-field performance and ended with a trail of insolvencies and, in the case of Rangers, liquidation. Extraordinarily, it wasnt the bank debt that finally brought about the death of the club, but unpaid taxes due to Her Majestys Revenue and Customs (HMRC).

The Murray years should have been recognised as exceptional, and the current, more stable financial landscape as the norm. Lessons should have been learned, but that wasnt to be in the case of Rangers. A new club was formed in 2012 with the assets of the liquidated club; it successfully applied for membership of the Scottish Football Association (SFA) and the then Scottish Football League (SFL), but after a difficult birth the new club has inherited the worst financial attributes of the old one and continues to live outwith its means and is financed by directors loans.