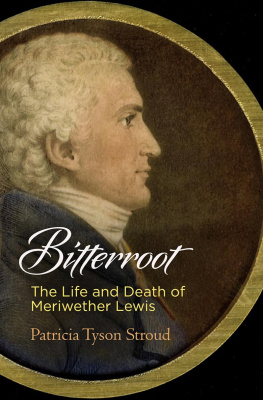

Bitterroot

Bitterroot

The Life and Death

of Meriwether Lewis

Patricia Tyson Stroud

Copyright 2018 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of

review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any

form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Stroud, Patricia Tyson, author.

Title: Bitterroot : the life and death of Meriwether Lewis / Patricia Tyson Stroud.

Description: 1st edition. | Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017026853 | ISBN 978-0-8122-4984-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Lewis, Meriwether, 17741809. | ExplorersWest (U.S.)Biography. | Lewis and Clark Expedition (18041806) | West (U.S.)Discovery and exploration. | West (U.S.)Description and travel.

Classification: LCC F592.7.L42 S77 2018 | DDC 917.8042092 [B] dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017026853

Frontispiece: Bitterroot (Lewisia rediviva). Plate from Curtiss Botanical

Magazine, volume 89 (1863). W. Fitsch, artist, del, et lith., call no.

QK1C9. Ewell Sale Stewart Library, courtesy of the Academy of Natural

Sciences of Drexel University.

Endpapers: Map of Lewis and Clarks track across the western portion of

North America from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, by order

of the Executive of the United States, 18046. Copied by Samuel Lewis

from the original drawing of William Clark. Library of Congress,

Geography and Map Reading Room, no. G4126.S12 2003.L42.

to Bob Peck

My long-time friend and fellow traveler

in the history of natural history

I do not believe there was ever an honest er man in Louisiana nor one who had pureor motives than Govr. Lewis.

William Clark

Letter to Jonathan Clark,

St. Louis, 26 August 1809

On the whole, the result confirms me in my first opinion that he was the fittest person in the world for such an expedition.

Thomas Jefferson

Letter to William Hamilton,

Washington, D.C., 22 March 1807

The unchanging Man of history is wonderfully adaptable both by his power of endurance and in his capacity for detachment. The fact seems to be that the play of his destiny is too great for his fears and too mysterious for his understanding.

Joseph Conrad

Contents

Color plates follow

The original spelling of Lewis and Clark and others in the expedition journals has been retained to give a better picture and understanding of the writers. Also, Jeffersons idiosyncratic grammar of not using capitals in the beginning of sentences and spelling the possessive its as its has been kept in quotation from his original letters from archives. Lewis used the same construction of its, probably picked up when, as Jeffersons secretary, he copied many documents for him. However, I have left alone the published versions of Jeffersons and Lewiss letters. Donald Jacksons editing of the collected letters relating to the expedition is a principal case in point.

In the quotations, words inserted between lines are in roman type, in angle brackets, while struck-out words are in italics and angle brackets.

A beautiful rose-colored flower with a nauseously distasteful root, the appropriately named bitterroot adorns the Rocky Mountains in late spring and early summer. The plant gives its name to the Bitterroot Mountains, that portion of the Rockies that was most difficult for the Lewis and Clark expedition to cross, both on the way west and the way back, and takes its Latin designation, Lewisia rediviva, from one of the leaders of that expedition, and the man who first brought this new genus to the attention of Western science. But who was this Meriwether Lewis?

He was a particularly interesting man: honorable, courageous, and intelligent, with an inquiring mind and a subtle sense of humor, sometimes playful with family and close friends. Often introspective, he could be strongly moved by events and express himself eloquently in writing about his emotional reactions. He had a remarkable grasp of natural science and especially botanydespite being largely self-taughtand inspired faith, respect, love, and yes, occasional dislike on the part of those who knew him. He was, admittedly, self-conscious, a bit arrogant, inflexible, and at times unwilling to control a hot temper, which rendered him vulnerable to presumed insult. His response to certain situations could be overly dramatic, but he was honest and true to the principles he believed in, and deeply loyal to those he loved and admired. He died young, but his accomplishments in his short life were impressive, and his resolve in the face of physical hardship and intellectual and emotional challenges was great.

And yet, how many times over the years I have been writing this biography have I met with the response, Meriwether Lewiswasnt he the one who committed suicide?

That Lewis died a violent death is incontrovertible, though the facts surrounding his demise are far from clear. The story of his suicide was circulated early on, as were accounts of his mental instability, alcoholism, and depression. Over the years, and especially of late, the narrative of a weak and troubled alcoholic depressive has dominated historiographic accounts, biographies, and films. Having failed as the governor of the Louisiana Territory, burdened by debt, and perhaps crazed by malaria, this version goes, Lewis shot himself in despair on his way east from St. Louis. But how do we reconcile this figure with the healthy, undaunted, resilient leader of the 18046 expedition? And what if Lewis did not suffer from depression or alcoholism at all? The cause of Lewiss death will probably remain a mystery after more than two hundred years as we can never know Lewis, sadly, but the nature and behavior of the man as documented in this book strongly suggest that he did not take his own life.

The seeds of denigrating historiography are embedded in a short biography that Thomas Jefferson wrote for the truncated 1814 edition of the Lewis and Clark Journals, published five years after Lewiss death in October 1809.

Shortly after Lewiss death, Jefferson had received a letter from the man who set off with Lewis from the fort where he stayed briefly on his way east, announcing Lewiss unwitnessed suicide and explaining that en route the governor had exhibited symptoms of a deranged mind. Jefferson quoted this phrase in his biography without having instigated an investigation of any kind into the circumstances of Lewiss death. The implication is therefore that this aberration was responsible for his suicide.