Books by William Ferris

Blues from the Delta

Mississippi Black Folklore: A Research Bibliography and Discography

Black Prose Narrative from the Mississippi Delta

Afro-American Folk Arts and Crafts

American Folklore Films and Videotapes: An Index

(coedited with Judy Peiser and Carolyn Lipson)

Images of the South: Visits with Eudora Welty and Walker Evans

Local Color

Folk Music and Modern Sound

(coedited with Sue Hart)

Encyclopedia of Southern Culture

(coedited with Charles Reagan Wilson)

You Live and Learn. Then You Die and Forget It All: Ray Lums Tales of Horses, Mules and Men

(Republished as Mule Trader: Ray Lums Tales of Horses, Mules and Men)

http:// www.upress.state.ms.us

Published 1998 by University Press of Mississippi

First published 1992 by Anchor Books, Doubleday

Copyright 1992 by William Ferris

Foreword Copyright 1992 by Eudora Welty

Reprinted by the permission of Russell & Volkening as agents for the author

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Print-on-Demand Edition

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Ferris, William R. Mule trader: Ray Lums tales of horses, mules and men/by William Ferris; with a forward by Eudora Welty.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p.).

Originally published: You live and learn, then you die and forget it all.

New York: Anchor Books, 1992.

Banner Books.

ISBN: 978-1-57806-086-6

1. Southern StatesSocial life and customs1865- 2. Lum, Ray, 1891-1976. 3. AuctioneersSouthern StatesBiography. 4. Lum, Ray, 1891-1976.

I. Lum, Ray, 1891-1976. II. Ferris, William R. You live and learn, then you die and forget it all. III. Title.

F216.F47 1998

975dc21

98-28245

CIP

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

Foreword

Eudora Welty

R ay Lum was a Mississippi mule trader and a remarkable man. William Ferris has brought this book into being in the only possible wayby ear. Thats the way Ray Lum had been telling it to him. Mr. Lum was above all a talker, listening to the way his tale went, keeping the ring true as he proceeded. His life as a mule trader and auctioneer, his stock in trade, his private well-being, his reputationall were gathered in, all would find expression in his tales. They speak to the source of his pleasure in the world, and in this, all tale tellers everywhere are the same.

Ray Lum could afford to be, and he was, a spendthrift: with so many tales to tell, surely hed be delightedtemptedto tell them all, and why not? All the tales were his to tell; and all of them were true: not one would falsify the teller. They were all always available to him, carried around like currency loose in a rich travelers pocket.

Thus we meet Ray Lum in the well-attuned company of his friend Bill Ferris: Ray Lum, a man born and bred to the practice of the country monologue.

Not all that long ago in any country pasture in America, standing contentedly motionless under a shade tree, a mule is exactly what you expected to see. At least you didnt expect not to see a mule. Today, your coming upon a mule in our landscape would be as rare as catching a glimpse of a distant cousin of his in the equus family, the zebra, trotting down the Interstate.

The mule is a sterile hybrid of a female horse and a male ass. (The hybrid offspring of a male horse and a female ass is a hinny.) The mule has a long head. The long face is somehow familiar; it might remind you of Disraeli. But the expression flickering along that lengthy graying countenance might be that of a cardsharp. William Faulkner has said that a mule would never allow himself to be driven through an opening unless he knew what was on the other side.

As Ray Lum knew, the strength and endurance of mules were put to use in the earliest days of settling the Delta in the state of Mississippi. Penetrating the wilderness of forest and canebrake (bear-ridden and panther-ridden) to hack out the first raw farmland, clearing and draining it, eventually planting it and harvesting it, could not have been accomplished without the mule. Mules worked in time to lay the railroads across America; they opened up the West. Eventually listed for shipment over the country were sugar mules, rice and cotton mules, levee mules, mine mules, railroad mules, mountaineer pack mules, all marketed by class according to need. Great numbers were destined for small barns, particularly in the South, where men such as Ray Lum made their livelihoods visiting from barn to barn, holding auction, buying and selling mules.

Mules should not be forgotten. They go back a long enough way they have a history. The mule was named in earliest times by the Greeks, medieval bestiaries say. Mulus was their word for millstone, which the animal was put under the yoke to draw in a circle for grinding. (This, in fact, is what we may catch him doing today if we find him on some farm in a remote part of the American South, where the mule still grinds cane to make syrup for the farmers table.)

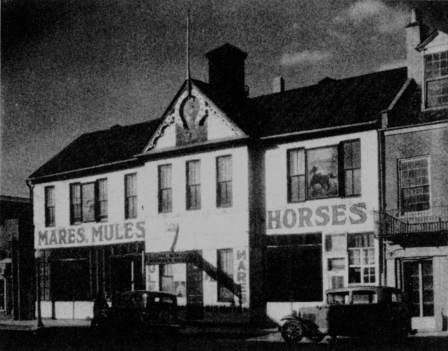

Yellowed panoramic photographs still hang in city halls and county courthouses here and there, showing mules lined up, crowded collar to collar, every pair of long ears crossed with the pair on either side, posed at the head of Main Street: a team at the start of some ambitious project, about to hear the holler to begin. The date would have been seventy-five to a hundred years ago.

All over the country mules were put to work at the building of dams, railroad tunnels, bridges. They also moved like an army upon the scenes of disastertornado destruction, forest fires, earthquake. During the Great Mississippi River Flood of 1927, Ray Lums barns and lots provided mules that labored to move thousands of endangered herds; and Ray Lums mules took part afterward in the building of the first Mississippi River levees.

The equal to, and the answer to, emergency, the mule was ready for the frontier, for war, for disaster, and for better times. So he labored his life away. (And the mules lifetime is twice as long as that of the horse, so we are told.)

Almost up until the peak of Ray Lums career, the mule was an integral part of American life. He was a taken-for-granted source of national strength, unbeatable for working in the cause, and in the name, and in the achievement, of progress.

But progress, attained, came in on its own terms. It rode in with the tractor. The mules career was over.

Mules have known battlefields for centuries back. A smartly barbered mule is portrayed in embroidery on the Bayeux Tapestry, the mount of a member of Williams Court. This mule must have taken part in the coming Battle of Hastingsof course on the winning side. Back even farther, mules are figures in story and fable.