Legends and Romances of Brittany

Lewis Spence

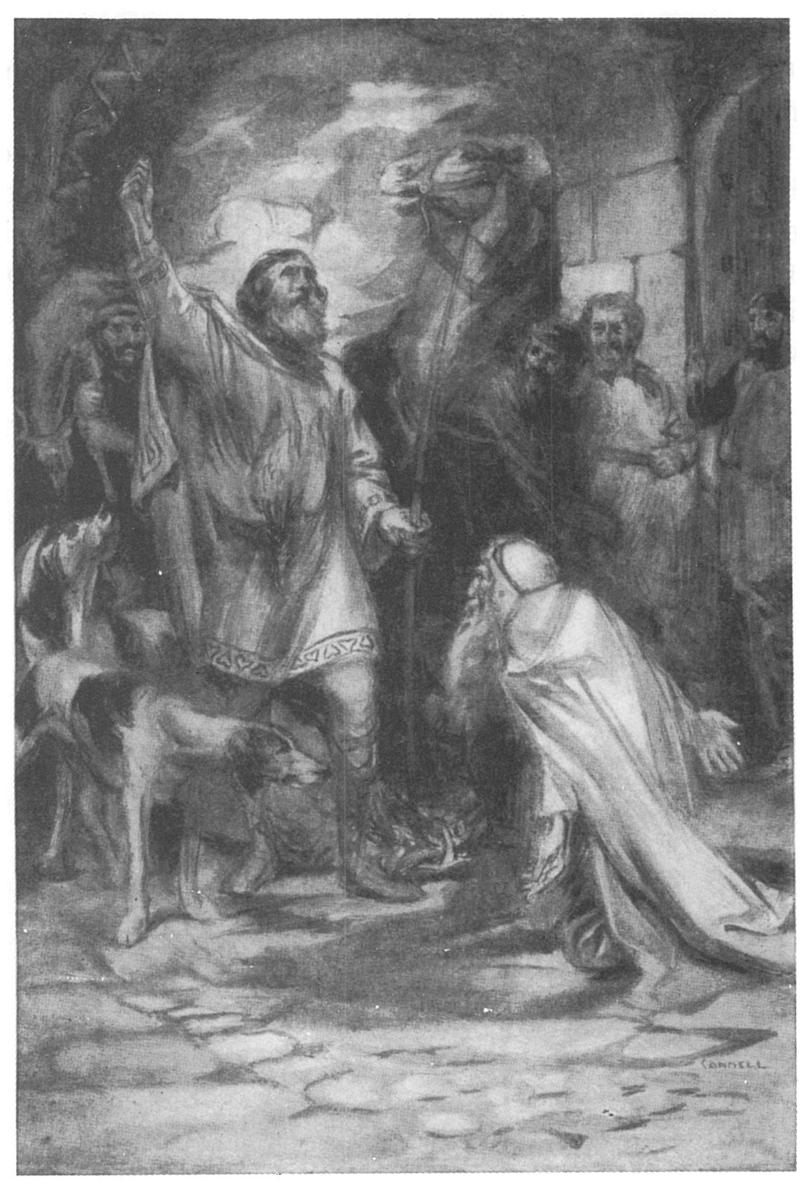

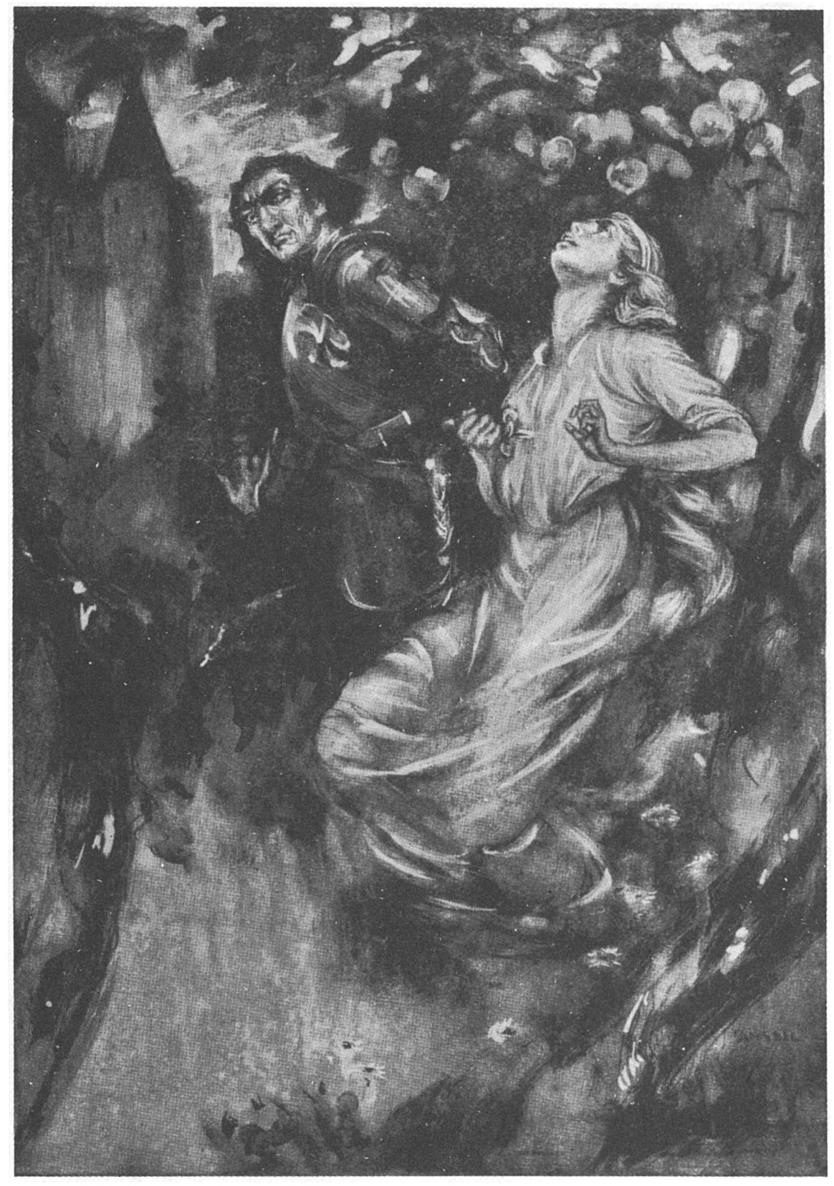

W. Otway canneil

Published in Canada by General Publishing Company, Ltd., 30 Lesmill Road, Don Mills, Toronto, Ontario.

Published in the United Kingdom by Constable and Company, Ltd., 3 The Lanchesters, 162-164 Fulham Palace Road, London W6 9ER.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 1997, is a republication of the work originally published by Frederick A. Stokes Company, New York, n.d. Several of the plates have been repositioned, and eight illustrations that appeared in color in the original edition are reprinted here in black and white. In addition, the original color frontispiece depicting Graelent and the Fairy-Woman has been moved to the front cover, so that this edition begins on page 3.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Spence, Lewis, 1874-1955.

Legends and romances of Brittany / Lewis Spence; illustrated by W. Otway Cannell.

p. cm.

Includes index.

9780486312880

1. LegendsFranceBrittany. 2. FolkloreFranceBrittany. 3. Brittany (France)Antiquities. I. Title.

DC611.B85S6 1997

398.209441dc21

96-54004

CIP

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501

PREFACE

A LTHOUGH the folk-tales and legends of Brittany have received ample attention from native scholars and collectors, they have not as yet been presented in a popular manner to English-speaking readers. The probable reasons for what would appear to be an otherwise incomprehensible omission on the part of those British writers who make a popular use of legendary material are that many Breton folk-tales strikingly resemble those of other countries, that from a variety of considerations some of them are unsuitable for presentation in an English dress, and that most of the folk-tales proper certainly possess a strong family likeness to one another.

But it is not the folk-tale alone which goes to make up the romantic literary output of a people; their ballads, the heroic tales which they have woven around passages in their national history, their legends (employing the term in its proper sense), along with the more literary attempts of their romance-weavers, their beliefs regarding the supernatural, the tales which cluster around their ancient homes and castlesall of these, although capable of separate classification, are akin to folk-lore, and I have not, therefore, hesitated to use what in my discretion I consider the best out of immense stores of material as being much more suited to supply British readers with a comprehensive view of Breton story. Thus, I have included chapters on the lore which cleaves to the ancient stone monuments of the country, along with some account of the monuments themselves. The Arthurian matter especially connected with Brittany I have relegated to a separate chapter, and I have considered it only fitting to include such of the lais of that rare and human songstress Marie de France as deal with the Breton land. The legends of those sainted men to whom Brittany owes so much will be found in a separate chapter, in collecting the matter for which I have obtained the kindest assistance from Miss Helen Macleod Scott, who has the preservation of the Celtic spirit so much at heart. I have also included chapters on the interesting theme of the black art in Brittany, as well as on the several species of fays and demons which haunt its moors and forests; nor will the heroic tales of its great warriors and champions be found wanting. To assist the reader to obtain the atmosphere of Brittany and in order that he may read these tales without feeling that he is perusing matter relating to a race of which he is otherwise ignorant, I have afforded him a slight sketch of the Breton environment and historical development, and in an attempt to lighten his passage through the volume I have here and there told a tale in verse, sometimes translated, sometimes original.

As regards the folk-tales proper, by which I mean stories collected from the peasantry, I have made a selection from the works of Gaidoz, Sbillot, and Luzel. In no sense are these translations; they are rather adaptations. The profound inequality between Breton folk-tales is, of course, very marked in a collection of any magnitude, but as this volume is not intended to be exhaustive I have had no difficulty in selecting material of real interest. Most of these tales were collected by Breton folk-lorists in the eighties of the last century, and the native shrewdness and common sense which characterize much of the editors comments upon the stories so carefully gathered from peasants and fishermen make them deeply interesting.

It is with a sense of shortcoming that I offer the reader this volume on a great subject, but should it succeed in stimulating interest in Breton story, and in directing students to a field in which their research is certain to be richly rewarded, I shall not regret the labour and time which I have devoted to my task.

L. S.

Table of Contents

THE DEATH OF MARGUERITE IN THE CASTLE OF TROGOFF

CHAPTER I: THE LAND, THE PEOPLE AND THEIR STORY

T HE romantic region which we are about to traverse in search of the treasures of legend was in ancient times known as Armorica, a Latinized form of the Celtic name, Armor (On the Sea). The Brittany of to-day corresponds to the departments of Finistre, Ctes-du-Nord, Morbihan, Ille-et-Vilaine, and Loire-Infrieure. A popular division of the country is that which partitions it into Upper, or Eastern, and Lower, or Western, Brittany, and these tracts together have an area of some 13,130 square miles.

Such parts of Brittany as are near to the sea-coast present marked differences to the inland regions, where raised plateaux are covered with dreary and unproductive moorland. These plateaux, again, rise into small ranges of hills, not of any great height, but, from their wild and rugged appearance, giving the impression of an altitude much loftier than they possess. The coast-line is ragged, indented, and inhospitable, lined with deep reefs and broken by the estuaries of brawling rivers. In the southern portion the district known as the Emerald Coast presents an almost subtropical appearance; the air is mild and the whole region pleasant and fruitful. But with this exception Brittany is a country of bleak shores and grey seas, barren moorland and dreary horizons, such a land as legend loves, such a region, cut off and isolated from the highways of humanity, as the discarded genii of ancient faiths might seek as a last stronghold.

Regarding the origin of the race which peoples this secluded peninsula there are no wide differences of opinion. If we take the word Celt as describing any branch of the many divergent races which came under the influence of one particular type of culture, the true originators of which were absorbed among the folk they governed and instructed before the historic era, then the Bretons are Celts indeed, speaking the tongue known as Celtic for want of a more specific name, exhibiting marked signs of the possession of Celtic customs, and having those racial characteristics which the science of anthropology until recently laid down as certain indications of Celtic relationshipthe short, round skull, swarthy complexion, and blue or grey eyes. It is to be borne in mind, however, that the title Celtic is shared by the Bretons with the fair or rufous Highlander of Scotland, the dark Welshman, and the long-headed Irishman. But the Bretons exhibit such special characteristics as would warrant the new anthropology in labelling them the descendants of that Alpine race which existed in Central Europe in Neolithic times, and which, perhaps, possessed distant Mongoloid affinities. This people spread into nearly all parts of Europe, and later in some regions acquired Celtic speech and custom from a Celtic aristocracy.