Table of Contents

Copyright 2011 by Laura Coelho, Christopher Dick, and Isa Hackett

Introduction copyright 2011 by Jonathan Lethem and Pamela Jackson

Afterword copyright 2011 by Richard Doyle

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce

selections from this book, write to Permissions,

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dick, Philip K.

The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick / edited by Pamela Jackson and Jonathan Lethem ;

Erik Davis, annotations editor.

p. cm.

Summary: "Preserved in typed and hand-written notes and journal entries,

letters and story sketches, Philip K. Dick's Exegesis is the magnificent and

imaginative final work of an author who dedicated his life to questioning the

nature of reality and perception, the malleability of space and time, and the

relationship between the human and the divine. The Exegesis of Philip K.

Dick will make this tantalizing work available to the public for the first time

in an annotated two-volume abridgement. Edited and introduced by Pamela

Jackson and Jonathan Lethem, this will be the definitive presentation of Dick's

brilliant, and epic, final work." Provided by publisher.

ISBN 978-0-547-54925-5 (hardback)

1. Dick, Philip K.Philosophy. 2. Dick, Philip K.Notebooks, sketchbooks, etc.

I. Jackson, Pamela (Pamela Renee) II. Lethem, Jonathan. III. Davis, Erik. IV. Title.

PS 3554. I 3 Z 46 2011

818'.5407dc23 2011028561

Book design by Melissa Lotfy

Printed in the United States of America

DOC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

An excerpt originally appeared in Playboy magazine.

IN MEMORIAM

PHILIP K. DICK

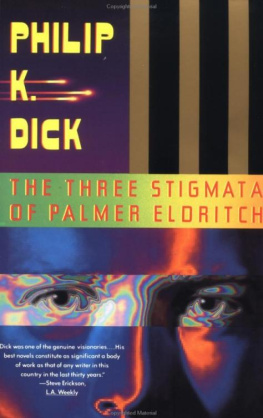

"Tomorrow morning," he decided, "I'll begin clearing away the sand of fifty

thousand centuries for my first vegetable garden. That's the initial step."

Philip K. Dick, The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch

What best can I do? Exactly what I've done. My voice for the voiceless.

Philip K. Dick, The Exegesis

Introduction

The beautiful and imperishable comes into existence due to the suffering of individual perishable creatures who themselves are not beautiful, and must be reshaped to form a template from which the beautiful is printed (forged, extracted, converted). This is the terrible law of the universe. This is the basic law; it is a fact. Also, it is a fact that the suffering of the individual animal is so great that it arouses an ultimate and absolute abhorrence and pity in us when we are confronted by it. This is the essence of tragedy: the collision of two absolutes. Absolute suffering leads tois the means toabsolute beauty. Neither absolute should be subordinated to the other. But this is not how it is: the suffering is subordinated to the value of the art produced. Thus the essence of horror underlies our realization of the bedrock nature of the universe.

This passage was written by the American novelist Philip K. Dick in 1980. Taken alone, the handful of lines might seem to be an extract from a lucid and elegant fugue on metaphysics and ontologyan inquiry, in other words, into matters of being and the purposes of consciousness, suffering, and existence itself. This particular passage would not strike anyone versed in philosophical or theological discourse as violently original, apart from an intriguing sequence of metaphorical slippagesprinted, forged, extracted, convertedand the almost subliminal conflation of "the universe" with a work of art.

What makes the passage unusual is the context in which it arose and the other kinds of writing that surround it. Despite a tone of conclusiveness, the passage represents a single inkling, passing in the night, among many thousands in the vast compilation of accounts of his own visionary experiences and insights that Dick committed to paper between 1974 and 1982. The topicsapart from suffering, pity, the nature of the universe, and the essence of tragedyinclude three-eyed aliens; robots made of DNA; ancient and suppressed Christian cults that in their essential beliefs forecasted the deep truths of Marxist theory; time-travel; radios that continue playing after being unplugged; and the true nature of the universe as revealed in the writings of the ancient philosopher Parmenides, in The Ti betan Book of the Dead, in Julian Jaynes's The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, and in Robert Altman's film Three Women.

The majority of these writings, that is to say, are neither familiar nor wholly lucid nor, largely, elegantnor were they intended, for the most part, for publication. Even when Dick, who was an autodidact if ever there was one, recapitulates some chestnut of philosophical or theological speculation, his own philosophical and theological writings remain unprecedented in their riotous urgency, their metaphorical verve, their self-satirizing charisma, and their lonely intimacy (as well as in their infuriating repetitiveness, stubbornness, insecurity, and elusiveness). They are unprecedented, in other words, because Philip K. Dick is Philip K. Dick, one of the more brilliant and unusual minds to make itself known to the twentieth century even before this (mostly) unpublished trove now comes to light.

Dick came to call this writing his "Exegesis." The process of its production was frantic, obsessive, and, it may be fair to say, involuntary. The creation of the Exegesis was an act of human survival in the face of a life-altering crisis both intellectual and emotional: the crisis of revelation. No matter how resistant we may find ourselves to this ancient and unfashionable notion, to approach the Exegesis from any angle at all a reader must first accept that the subject is revelation, a revelation that came to the person of Philip K. Dick in February and March of 1974 and subsequently demanded, for the remainder of Dick's days on earth, to be understood. Its pages represent Dick's passionate commitment to explicating the glimpse with which he had been awarded or cursednot for the sake of his own psyche, nor for the cause of the salvation of humankind, but precisely because those two concerns seemed to him to be one and the same.

The attempt eventually came to cover over eight thousand sheets of paper, largely handwritten. Dick often wrote through the night, running an idea through its paces over as many as a hundred sheets during a sleepless night or in a series of nights. These feats of superhuman writing are astonishing to contemplate; they impressed even an established graphomaniacal writer like Dick, who had once written seven novels in a single year. The fundamental themes of the Exegesis come as no surprise. The body of work that established Dick's reputationhis forty-odd realist and surrealist novels written between 1952 and his death in 1982concerns itself with questions like "What is it to be human?" and "What is the nature of the universe?" These metaphysical, ethical, and ontological themes enmesh his work, even from its very beginnings in domestic melodrama, science fiction adventure, and humor, in an atmosphere of philosophical inquiry.

Dick increasingly came to view his earlier writingsspecifically his science fiction novels of the 1960sas an intricate and unconscious precursor to his visionary insights. Thus, he began to use them, as much as any ancient text or the Encyclopedia Britannica, as a source for his investigations. Never, to our knowledge, has a novelist borne down with such eccentric concentration on his own oeuvre, seeking to crack its code as if his life depended on it. The writing in these pages represents, perhaps above all, a laboratory of

Next page