Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd

Level 1, 221 Drummond Street

Carlton VIC 3053, Australia

www.blackincbooks.com

Introduction and selection Benjamin Law 2019

Benjamin Law asserts his moral rights in the collection.

Individual stories retained by the authors, who assert their rights to be known as the author of their work.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

9781760640866 (paperback)

9781743821084 (ebook)

Cover by Grace Lee

Text design and typesetting by Tristan Main

Introduction

Benjamin Law

Some things I wish Id had, growing up queer in Australia:

clothes that fit

less acne

wavy hair like the local hot white surfer boys

queer role models

stories that spoke to me

gay porn.

Eventually Id figure out how to access the first three things by shopping in Asian clothing outlets, getting a prescription for Roaccutane, and paying good money for a bad Korean man-perm I dont particularly want to discuss right now, please respect my privacy. But those last three things queer people, stories and depictions of queer sex proved much harder to find, and I craved them with a desperation that bordered on hunger. Growing up in pre-dial-up-internet Queensland, the last mainland Australian state to decriminalise homosexuality, any scrap of queer connection or recognition was a hard thing to come by.

So what did I have? Well, there was the H volume of our familys set of Encyclopdia Britannica. As a kid, when I was sure no one was around, Id fervently flip to the entry on homosexuality, feeling sick, my heart thumping. Though it couldnt have been more than one or two paragraphs long, the entry represented the entirety of all knowledge available to me at the time about being gay, beyond snickering schoolyard jokes about AIDS and anal sex, which I weakly laughed along with.

As a teenager, there was our household copy of Everything a Teenage Boy Should Know the popular coming-of-age sex-education tome every parent seemed to give Australian kids born in the 1970s and 1980s, written by Sydney doctor John F. Knight. In Chapter 14, titled Unnatural Sex, Knight wrote of gay sex:

The method most commonly attributed to males indulging in this form of sexual gratification is intercourse (if such a word can be used in this context) via the back passage. Most normal people would regard this form of indulgence as less than attractive, and indeed downright repulsive.

Lovely thing for a twelve-year-old to read. Truly. But by then, puberty was hitting hard, and not even Dr Knight calling gay sex repulsive could stop me from scouring TV Week every Monday for art-house movies on SBS that were rated MA, featuring S (sex scenes), N (nudity) and A (adult themes), and setting the VHS timer accordingly. The A was especially important: adult themes combined with sex and nudity usually meant queer stuff. Without A it was mostly just heterosexual sex, and who wanted that? While SBS movies rated MA (A, S, N) werent exactly the piping-hot gay porn that I craved, watching them throughout the late 1990s meant I was thoroughly familiar with the collected works of Pedro Almodvar, Todd Haynes and Gregg Araki by the age of fifteen. One benefit of being a repressed gay teen in the suburbs: you come out literate in art-house cinema auteurs.

The internet was a slow revolution. It was only in my final years of high school that my parents riddled with divorce guilt caved and bought us a Hewlett-Packard desktop computer. It was state-of-the-art, with a whopping sixteen-gigabyte (!) hard drive, a base roughly the size of a small microwave and a modem built inside the computer. We were living in the future. Needless to say, the first thing I did when I got online in private was to look up gay porn on AltaVista. As one single explicit gay jpeg of two white meatheads going at it in jockstraps loaded frame by painful frame I watched with horror as the monitor was infested with pop-up porn advertisements from hell. As footsteps approached, it was a mad sweaty scramble to simultaneously hide the plague-like pop-ups and my popped-up boner, the whole exercise feeling like I was being punished before Id got any reward.

*

On reflection, its odd that I grew up without meeting any other openly queer people, and with so little exposure to stories with which I could identify. As Oliver Reeson writes in their essay about being non-binary:

When I look back on my own life, I feel the weight of not realising earlier who I was, of being scared to tell the whole story. And yet, how could I realise I was a non-binary person when I did not even know of the concept until I was already an adult? How could I have grown up as a non-binary person when it was not a story I had ever heard?

As a reader, I look for two things in other peoples stories. The first is the kind of self-recognition Reeson talks about. For queer people its especially important, because while other forms of prejudice like racism can make you feel just as alone and isolated, ethnic minorities like me go home to families and communities who share our backgrounds and experiences, and affirm who we are. Queer kids growing up typically dont have that. I didnt. That feeling of belonging of understanding you are not alone and not insane is a core human need. If we cant get that from the people around us, we need stories.

The second thing I look for in stories is the opposite of selfrecognition: experiences completely outside my own personal framework. As much as queer people share experiences of marginalisation, fear and facing baseless assumptions about who we are, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and/or non-binary people also have their own discrete experiences and histories. Our capacity to stay curious and listen to each others stories is paramount. Embracing difference rather than relying on simplistic platitudes like were all the same is how we learn to forge respect. In any case, sameness is boring. Sameness is the opposite of diversity. And sameness has never been a prerequisite for queer equality.

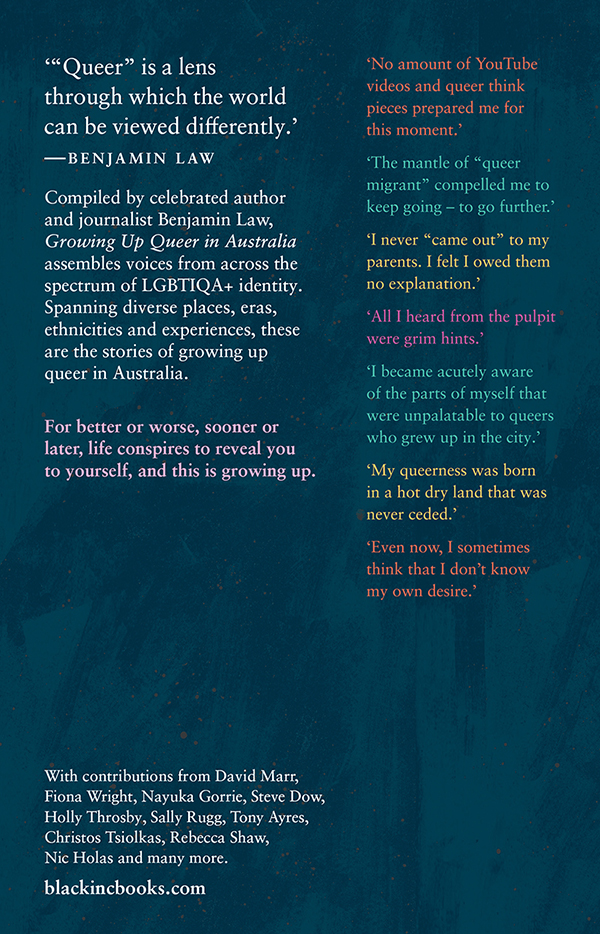

Yes: weve chosen to go with queer in the title of this anthology. We couldve called it Growing Up LGBTIQA+. Personally, I dont mind the unwieldiness of that acronym I like how it makes us vigilant about who might be left out but it wouldve made life slightly hellish for booksellers trying to search for it. That said, I acknowledge that there is a sting associated with the word queer especially for those from older generations, against whom queer was used as a slur and a weapon. Balanced against that, though, there is also a proud and rich history of defiantly reclaiming the word queer for ourselves. LGBTIQA+ people from racial minorities began to identify as queer in response to parts of the gay and lesbian community becoming more conservative, assimilationist and palatable. Queer is not just an identity, but a lens through which the world can be viewed differently. Its a noun, an adjective and perhaps most importantly a verb. To queer something is to subvert, interrogate and flip which all these stories do in their own way.