The

S USPICIONS

of

MR W HICHER

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Queen of Whale Cay

The

SUSPICIONS

of

MR WHICHER

or THE MURDER at ROAD HILL HOUSE

KATE SUMMERSCALE

First published in Great Britain 2008

Copyright & Kate Summerscale

This electronic edition published 2009 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

The right of Kate Summerscale to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 36 Soho Square, London W1D 3QY

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 978-1-40880-158-1

www.bloomsbury.com/katesummerscale

Visit www.bloomsbury.com to find out more about our authors and their books.

You will find extracts, authors interviews, author events and you can sign up for newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers.

To my sister, Juliet

'Do you feel an uncomfortable heat at the pit of your

stomach, sir? and a nasty thumping at the top of your head?

Ah! not yet? It will lay hold of you... I call it the

detective-fever'

From The Moonstone (1868) by Wilkie Collins

CONTENTS

This is the story of a murder committed in an English country house in 1860, perhaps the most disturbing murder of its time. The search for the killer threatened the career of one of the first and greatest detectives, inspired a 'detective-fever' throughout England, and set the course of detective fiction. For the family of the victim, it was a murder of unusual horror, which threw suspicion on almost everyone within the house. For the country as a whole, the murder at Road Hill became a kind of myth - a dark fable about the Victorian family and the dangers of detection.

A detective was a recent invention. The first fictional sleuth, Auguste Dupin, appeared in Edgar Allan Poe's 'The Murders in the rue Morgue' in 1841, and the first real detectives in the English-speaking world were appointed by the London Metropolitan Police the next year. The officer who investigated the murder at Road Hill House - Detective-Inspector Jonathan Whicher of Scotland Yard - was one of the eight men who formed this fledgling force.

The Road Hill case turned everyone detective. It riveted the people of England, hundreds of whom wrote to the newspapers, to the Home Secretary and to Scotland Yard with their solutions. It helped shape the fiction of the 1860s and beyond, most obviously Wilkie Collins' The Moonstone , which was described by T.S. Eliot as the first and best of all English detective novels. Whicher was the inspiration for that story's cryptic Sergeant Cuff, who has influenced nearly every detective hero since. Elements of the case surfaced in Charles Dickens' last, unfinished novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood . And although Henry James's terrifying novella The Turn of the Screw was not directly inspired by the Road Hill murder - James said he based it on an anecdote told to him by the Archbishop of Canterbury - it was alive with the eerie doubts and slippages of the case: a governess who might be a force for good or evil, the enigmatic children in her charge, a country house steeped in secrets.

A Victorian detective was a secular substitute for a prophet or a priest. In a newly uncertain world, he offered science, conviction, stories that could organise chaos. He turned brutal crimes - the vestiges of the beast in man - into intellectual puzzles. But after the investigation at Road Hill the image of the detective darkened. Many felt that Whicher's inquiries culminated in a violation of the middle-class home, an assault on privacy, a crime to match the murder he had been sent to solve. He exposed the corruptions within the house-hold: sexual transgression, emotional cruelty, scheming servants, wayward children, insanity, jealousy, loneliness and loathing. The scene he uncovered aroused fear (and excitement) at the thought of what might be hiding behind the closed doors of other respectable houses. His conclusions helped to create an era of voyeurism and suspicion, in which the detective was a shadowy figure, a demon as well as a demi-god.

Everything we know about Road Hill House is determined by the murder that took place there on 30 June 1860. The police and magistrates turned up hundreds of details of the building's interior - handles, latches, footprints, nightclothes, carpets, hotplates - and of its inhabitants' habits. Even the interior of the victim's body was exposed to the public with an unflinching, forensic candour that now seems startling.

Because each piece of information that has come down to us was given in answer to an investigator's question, each is the mark of a suspicion. We know who called at the house on 29 June because one of the callers might have been the killer. We know when the house's lantern was fixed because it might have illuminated the path to the scene of the murder. We know how the lawn was cut because a scythe might have served as the weapon. The resulting portrait of life in Road Hill House is hungrily attentive, but it is also incomplete: the investigation into the killing was like a torch swung round onto sudden movements, into corners and up stairwells. Everyday domestic events were lit with possible meanings. The ordinary was made sinister. The method of the murder seeped into the gathering detail, in the witnesses' repeated references to hard and soft surfaces, such as knives and cloths, and to openings and closings, incisions and bolts.

For as long as the crime went unsolved, the inhabitants of Road Hill House were cast variously as suspects, conspirators, victims. The whole of the secret that Whicher guessed at did not emerge until many years after all of them had died.

This book is modelled on the country-house murder mystery, the form that the Road Hill case inspired, and uses some of the devices of detective fiction. The content, though, aims to be factual. The main sources are the government and police files on the murder, which are held in the National Archives at Kew, south-west London, and the books, pamphlets, essays and newspaper pieces published about the case in the 1860s, which can be found in the British Library. Other sources include maps, railway timetables, medical textbooks, social histories and police memoirs. Some descriptions of buildings and landscapes are from personal observation. Accounts of the weather conditions are from press reports, and the dialogue is from testimony given in court.

In the later stages of the story the characters disperse - notably to London, the city of the detectives, and to Australia, a land of exiles - but most of the action of the book takes place in an English village over one month in the summer of 1860.

AT ROAD HILL HOUSE

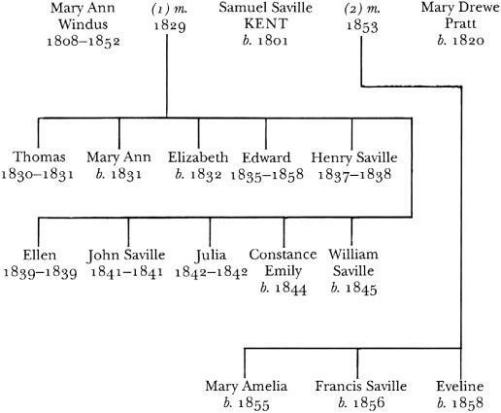

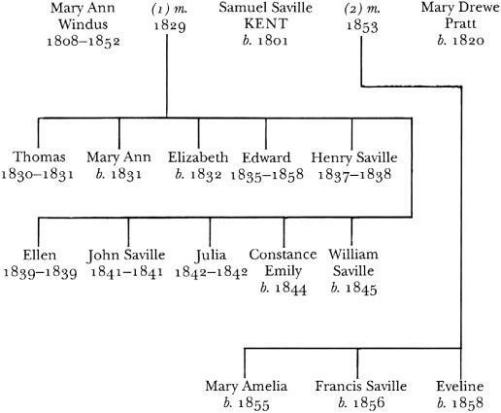

Samuel Kent, sub-inspector of factories, aged 59 in June 1860

Mary Kent, nee Pratt, Samuel's second wife, 40

Mary Ann Kent, daughter of Samuel Kent's first marriage, 29

Elizabeth Kent, daughter of Samuel Kent's first marriage, 28

Next page