A DAVID FICKLING BOOK

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright 2010 by Andrew Mulligan

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by David Fickling Books, an imprint of Random House Childrens Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

David Fickling Books and the colophon are trademarks of David Fickling.

Visit us on the Web! www.randomhouse.com/teens

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at www.randomhouse.com/teachers

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mulligan, Andy.

Trash / Andy Mulligan. 1st American ed.

p. cm.

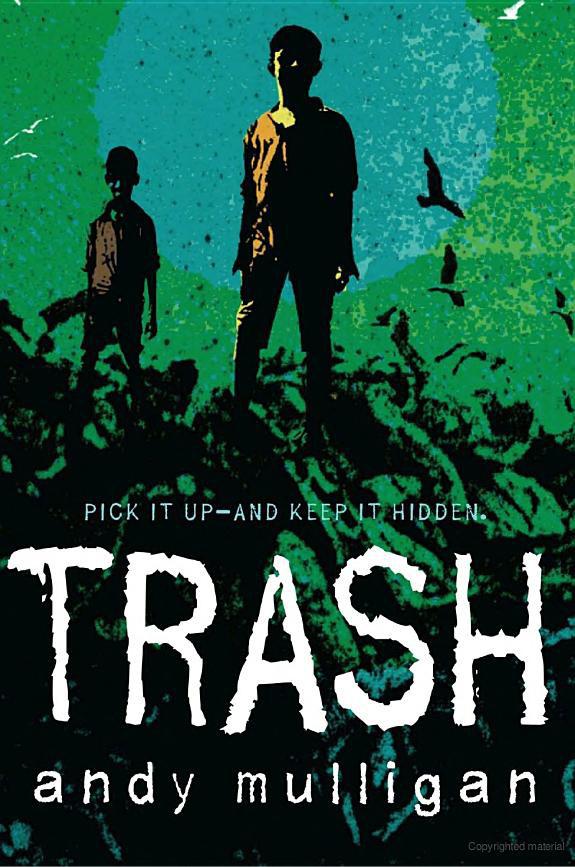

Summary: Fourteen-year-olds Raphael and Gardo team up with a younger boy, Rat, to figure out the mysteries surrounding a bag Raphael finds during their daily life of sorting through trash in a third-world countrys dump.

eISBN: 978-0-375-89843-3

[1. Mystery and detective stories. 2. PovertyFiction. 3. Refuse and refuse disposalFiction. 4. Developing countriesFiction. 5. Political corruptionFiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.M918454Tr 2010

[Fic]dc22

2010015940

Random House Childrens Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

Contents

PART ONE

1

My name is Raphael Fernndez and I am a dumpsite boy.

People say to me, I guess you just never know what youll find, sifting through rubbish! Today could be your lucky day. I say to them, Friend, I think I know what I find. And I know what everyone finds, because I know what weve been finding for all the years Ive been working, which is eleven years. Its the one word: stuppa, which means and Im sorry if I offend its our word for human muck. I dont want to upset anyone, thats not my business here. But theres a lot of things hard to come by in our sweet city, and one of the things too many people dont have is toilets and running water. So when they have to go, they do it where they can. Most of those people live in boxes, and the boxes are stacked up tall and high. So, when you use the toilet, you do it on a piece of paper, and you wrap it up and put it in the trash. The trash bags come together. All over the city, trash bags get loaded onto carts, and from carts onto trucks or even trains youd be amazed at how much trash this city makes. Piles and piles of it, and it all ends up here with us. The trucks and trains never stop, and nor do we. Crawl and crawl, and sort and sort.

Its a place they call Behala, and its rubbish-town. Three years ago it was Smoky Mountain, but Smoky Mountain got so bad they closed it down and shifted us along the road. The piles stack up and I mean Himalayas: you could climb for ever, and many people do up and down, into the valleys. The mountains go right from the docks to the marshes, one whole long world of steaming trash. I am one of the rubbish boys, picking through the stuff this city throws away.

But you must find interesting things? someone said to me. Sometimes, no?

We get visitors, you see. Its mainly foreigners visiting the Mission School, which they set up years ago and just about stays open. I always smile, and I say, Sometimes, sir! Sometimes, maam!

What I really mean is, No, never because what we mainly find is stupp.

What you got there? I say to Gardo.

What dyou think, boy? says Gardo.

And I know. The interesting parcel that looked like something nice wrapped up? What a surprise! Its stupp, and Gardos picking his way on, wiping his hands on his shirt and hoping to find something we can sell. All day, sun or rain, over the hills we go.

You want to come see? Well, you can smell Behala long before you see it. It must be about two hundred football pitches big, or maybe a thousand basketball courts I dont know: it seems to go on for ever. Nor do I know how much of it is stupp, but on a bad day it seems like most of it, and to spend your life wading through it, breathing it, sleeping beside it well maybe one day youll find something nice. Oh yes.

Then one day I did.

I was a trash boy since I was old enough to move without help and pick things up. That was what? three years old, and I was sorting.

Let me tell you what were looking for.

Plastic, because plastic can be turned into cash, fast by the kilo. White plastic is best, and that goes in one pile; blue in the next.

Paper, if its white and clean that means if we can clean it and dry it. Cardboard also.

Tin cans anything metal. Glass, if its a bottle. Cloth or rags of any kind that means the occasional T-shirt, a pair of pants, a bit of sack that wrapped something up. The kids round here, half the stuff we wear is what we found, but most we pile up, weigh and sell. You should see me, dressed to kill. I wear a pair of hacked-off jeans and a too-big T-shirt that I can roll up onto my head when the sun gets bad. I dont wear shoes one, because I dont have any, and two, because you need to feel with your feet. The Mission School had a big push on getting us boots, but most of the kids sold them on. The trash is soft, and our feet are hard as hooves.

Rubber is good. Just last week we got a freak delivery of old tyres from somewhere. Snapped up in minutes, they were, the men getting in first and driving us off. A half-good tyre can fetch half a dollar, and a dead tyre holds down the roof of your house. We get the fast food too, and thats a little business in itself. It doesnt come near me and Gardo, it goes down the far end, and about a hundred kids sort out the straws, the cups and the chicken bones. Everything turned, cleaned and bagged up cycled down to the weighers, weighed and sold. Onto the trucks that take it back to the city, round it goes. On a good day Ill make two hundred pesos. On a bad, maybe fifty? So you live day to day and hope you dont get sick. Your life is the hook you carry, there in your hand, turning the trash.

Whats that you got, Gardo?

Stupp. What about you?

Turn over the paper. Stupp.

I have to say, though: Im a trash boy with style. I work with Gardo most of the time, and between us we move fast. Some of the little kids and the old people just poke and poke, like everythings got to be turned over but among the stupp, I can pull out the paper and plastic fast, so I dont do so bad. Gardos my partner, and we always work together. He looks after me.

2

So where do we start?

My unlucky-lucky day, the day the world turned upside down? That was a Thursday. Me and Gardo were up by one of the crane-belts. These things are huge, on twelve big wheels that go up and down the hills. They take in the trash and push it up so high you can hardly see it, then tip it out again. They handle the new stuff, and youre not supposed to work there because its dangerous. Youre working under the trash as its raining down, and the guards try to get you away. But if you want to be first in line if you cant get right inside the truck, and that is very dangerous: I knew a boy lost an arm that way then its worth going up by the belt. The trucks unload, the bulldozers roll it all to the belts, and up it comes to you, sitting at the top of the mountain.

Thats where we are, with a view of the sea.

Gardos fourteen, same as me. Hes thin as a whip, with long arms. He was born seven hours ahead of me, onto the same sheet, so people say. Hes not my brother but he might as well be, because he always knows what Im thinking, feeling even what Im about to say. The fact that hes older means he pushes me around now and then, tells me what to do, and most of the time I let him. People say hes too serious, a boy without a smile, and he says, So show me something to smile at. He can be mean, its true but then again hes taken more beatings than me so maybe hes grown up faster. One thing I know is Id want him on my side, always.