Copyright 2007 by David Pitts

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America.

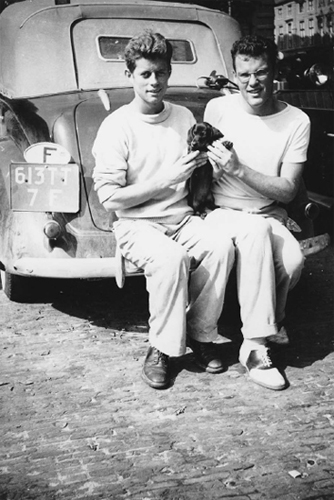

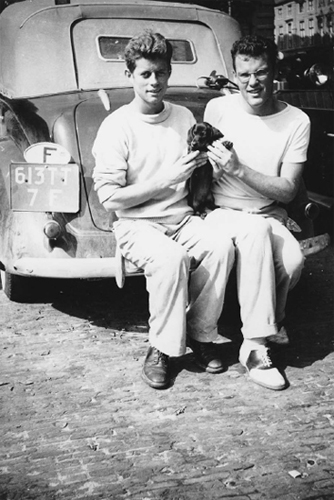

All photographs, except one, appear courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Library and Columbia Point, Boston, Massachusetts. The remaining photograph appears courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation. It is located at the same address.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

First edition Carroll & Graf edition 2007

First Da Capo Press paperback edition 2008

ISBN: 978-0-78673-224-1

Published by Da Capo Press

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

www.dacapopress.com

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchase in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia PA 19103, or call (800) 255-1514, or e-mail

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

For more information and to hear a short phone call between Jack and Lem, please visit www.jackandlem.com.

For my mother, Rachel (19212005)

Who believed in JFK and me

Contents

O n the morning of January 21, 1961, I was in the living room of my parents home in Manchester, England. There was little daytime television in the country then. But I noticed in the newspaper that one of the two networks was showing a videotape of the inaugural address of President John F. Kennedy. Americans had been able to watch it live the day before, but in those days before satellite transmissions, videotape arrived by airplane much delayed. At thirteen, I was interested, but not very interested, in the events across the pond. Probably because I had nothing better to do that day, I switched on the television to watch the new American president.

I recall that as John Kennedy began talking, I was almost instantly riveted by the man and his message. My mother was in the room at the time. Not being similarly persuaded, she switched on the vacuum cleaner, drowning out a section of the presidents speech. Fortunately, I was able to convince her to switch it off, so I was able to hear most of it. I remember saying to her, This guy sounds different, Mom (or maybe it was, This bloke sounds different). In a very real sense, the seed for this book was planted on that day forty-five years ago. In the ensuing four and a half decades, I devoured all the information I could get my hands on about John Kennedy, which included the many television documentaries as well as books and newspaper articles. I was not always impressed with what I eventually learned about him, particularly after a U.S. Senate committee during the mid-1970s detailed the existence of largescale covert operations against Cuba, including sabotage, long after the Bay of Pigs invasion early in his administration ended in failure. Nevertheless, I remained fascinated by the man and his legacy and generally approving of his presidency, particularly in light of the caliber of leaders who followed him.

In fact, Camelot was part of the reason I emigrated right after college. It was the thing to do then, although most Brits who left went to Canada or Australia, not the United States. The British government charitably referred to us as the brain drain. I arrived in the United States in 1969 and have been writing about America in America ever since. When I left full-time journalism in 2003, I knew I would write a John Kennedy book. When I told friends of my intention, however, the general reaction was: not another JFK book? What is to be written that has not already been written? It was a good question, especially since I wanted to write a book about JFKs political legacy, a territory well traveled by scores of other authors. At a minimum, I thought I should tell a story about JFK that had never been told before.

In reading JFK books over the years, I had become aware of a man named Lem Billings, who was identified as John Kennedys best friend from his days at prep school. The two men remained close until JFK was killed in Dallas. A few authors interviewed Lem before his death in 1981, seeking out additional information about JFK. But there was little about Lem himself in the various books, probably because he was not a member of the Kennedy administration. The role he played in John Kennedys life seemed important but was obscure. I was curious. Heres my book, I told myself. Why not explore the friendship between the two men and no doubt uncover Lems hitherto unknown influence on JFKs political philosophy? I was sure Lem was a key player, since I could not conceive of JFK maintaining a close friendship with any man who was not political.

It was not to be. As I began research for the book and started interviewing people whod known them both, I quickly learned that politicsin the conventional sense of that wordplayed only an indirect role in the friendship between John Kennedy and Lem Billings. I discovered that their attachment was much deeper and was rooted not in politics but in fundamental human needs. It flourished despite their differing interests and temperaments, as friendships often do. Everyone close to them witnessed their mysterious bond, although few claim to have fully understood it. For most of JFKs inner political circle, Lem was an enigma.

That is not to say, however, that Lem had no political function in JFKs life. Although he had little interest in policy or the workings of government, Lem played a crucial role in listening to JFK vent during the great events of his presidency, most critically during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. During those thirteen days, Lem encouraged JFK to have confidence in his own instincts rather than to follow the near-unanimous advice he received to mount an invasion of Cuba, an action that we now know would almost assuredly have led to nuclear war. John Kennedys absolute trust in Lem and comfort level in discussing matters with him freely and candidlyin a way he could not do with aides and advisorshelped reassure the president at a time of maximum danger. No one, I learned, could stiffen JFKs resolve and improve his mood, political or otherwise, quite like Lem Billings.

Lems role behind the scenes at the White House in soothing the president and nurturing his self-confidence, which has not been known until now, was not inconsequential for someone close to a leader with his finger on the nuclear button. And it should not be unimportant to historians, even though Lem clearly was not someone to whom JFK routinely turned for detailed advice on politics in the way he did, for example, with Ted Sorensen. Lem Billings played a much larger and more complex role in John Kennedys life than that of political advisor. He was JFKs oldest and best friend. Inevitably, politics was part of their friendship, especially in the later years, but it was far from being the glue that held them together.

Next page