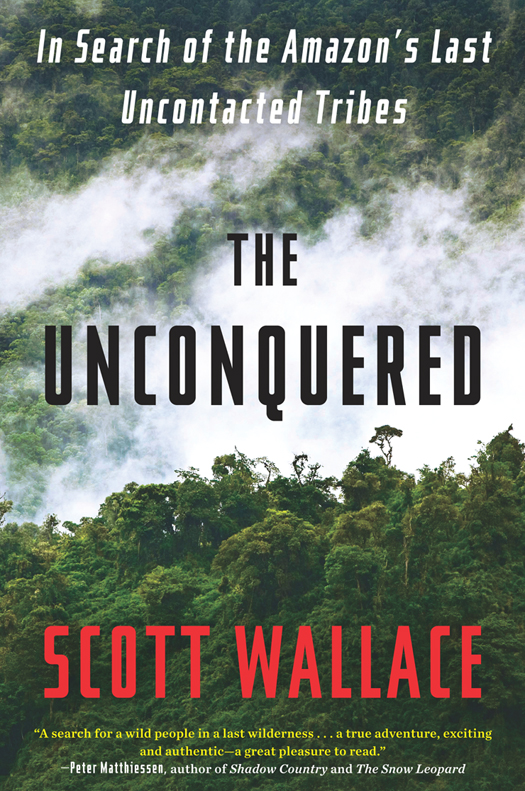

Copyright 2011 by Scott Wallace

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the

Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wallace Scott.

The unconquered : in search of the Amazons last uncontacted tribes / Scott Wallace.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Indians of South AmericaAmazon River RegionSocial life and customs. 2. Wallace, ScottTravelAmazon River Region. 3. Amazon River RegionDescription and

travel. I. Title.

F2519.1.A6W35 2011

981.1dc22

2011006717

eISBN: 978-0-307-46298-5

Photograph insert 2011 by Scott Wallace unless otherwise noted.

Photograph on 2011 by Scott Wallace

Jacket design by Jennifer OConnor

Jacket photograph by Arctic-Images/Workbook Stock/Getty Images

v3.1

For Mackenzie, Aaron, and Ian,

and my parents,

Robert and Flora Wallace,

who would have been proud

to hold this in their hands

Poor Aru, he had no way of knowing that the whites were not a tribe like ours or like others that occupy a single riverbank, or two at most. He didnt know that they were the first of a whole world of people, an inexhaustible anthill, occupying the entire earth, insatiably swarming over the globe. In the following years, more and more started arriving. They continue to surround us to this day. They have already taken possession of the side of sunrise; someday they will take the forests of the sunset. Then we will be reduced to an islet in a sea of whiteness.

From Mara by Darcy Ribeiro,

translated by E. H. Goodland and Thomas Colchie

Contents

Prologue

Deep In, Far Back

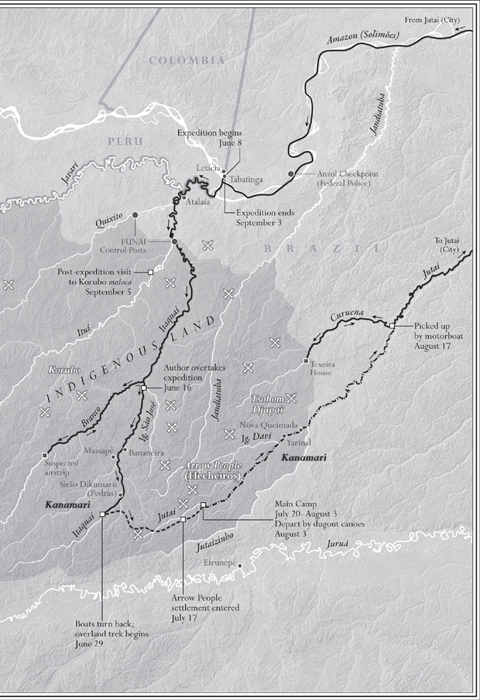

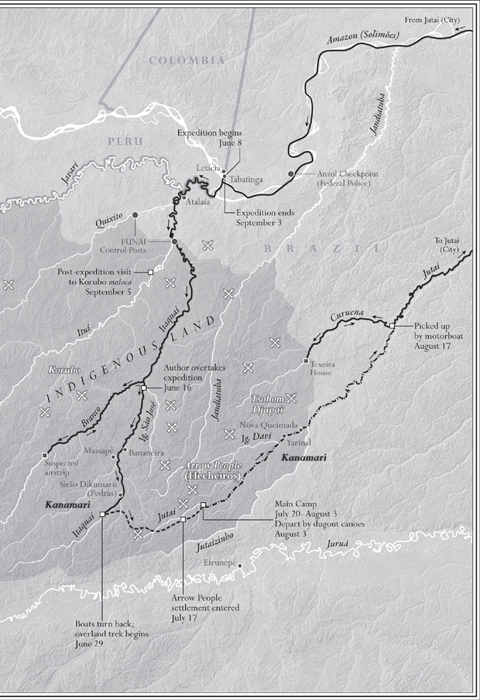

W E FOUND FRESH TRACKS in the morning, footprints in the soggy mud, adult size 8 or 9, and no more than a few hours old. They pointed in the same direction our column was headed, deep into the farthest reaches of the Amazon jungle.

We walked single file through dense foliage and lianas thick as anacondas that dangled 150 feet from the treetops to the jungle floor. Monkeys hooted and chattered somewhere above us, their calls punctuated by the four-note cry of a screaming piha bird in the canopy. I followed close on the heels of Sydney Possuelo, the expedition leader. Were probably the only ones who have ever walked hereus and the Indians, he said. By Indians, he meant not the twenty men from three different tribes who formed the core of our expeditionary force, but rather the mysterious flecheiros, the People of the Arrow. ndios bravos. Wild Indians.

A day earlier our scouts had glimpsed a pair of naked Indians near the river, called out to them, then watched as they fled across a makeshift bridge and vanished into the forest. Now, the most visible evidence of the panic that must have been spreading through their realm lay right here before usnot so much in the footprints themselves as in the long spaces between them, which suggested the full stride of a runner bearing urgent news.

There was no way to know exactly how the tribe would react to our presence. They had little reason to view us as anything other than a hostile, invasive army. And not unreasonably, for despite our best intentions, any direct contact with the Arrow People could be disastrous. The tribe had no immunity to the germs we carried. We were not doctors and carried few medicines. We, too, were in danger; there was little chance for escape in the walled-in jungle, if their curare-tipped arrows began to fly.

Yet, who among usyes, even the purist Possuelodidnt secretly hope for a first contact: that moment on the cutting edge of history when complete and utter strangers from separate universes stand face-to-face, look one another in the eye, and recognize their common humanity? That was how I liked to imagine itsmiles, handshakes, an exchange of giftsa rewriting of the epochal encounters at Roanoke or Tenochtitln. An experience for all time, a tale to recount to wide-eyed children and grandchildren: Come on, Grandpa, tell us about the time you met the wild Indians in the jungle! Wed bedazzle the world with images of the Stone Age savages, appear on the Today show, become celebrity journalists. Maybe Id get a book contract.

Possuelo stopped dead in his tracks. A freshly hacked sapling, dangling by a shred of bark, hung across the path before us. The makeshift gate couldnt have halted a toddler, much less our contingent of nearly three dozen well-armed men. Yet, it bore a messageand a warningthat Possuelo instantly recognized and respected. This is universal language in the jungle, he whispered. It means: Stay out. Go no farther.

We were getting close to their village. Any encounter would mean an abrupt and definitive end to a way of life thousands of years old, which is exactly what we were there to prevent.

We had located the inner sanctum of the Arrow People. Now it was time to back off, if it wasnt already too late.

PART I

Into the Amazon

CHAPTER 1

A Rumor of Savages

T HE CALL THAT LED ME from New York deep into the Amazon came one day in early June from Oliver Payne, a senior editor at National Geographic. I was settling into a summer sublet, a cavernous two-bedroom apartment on the ground floor of a gray granite building on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, having just returned from several months in Brazil, where Id been reporting on environmental devastation in the Amazon. It was that idyllic time of year when winter is a dim memory and the sun glows benevolently before the blast-furnace heat of midsummer. I was looking forward to a summer to recoupto solidify family ties and make life decisions about where I was going to sink roots after bouncing around for so many years. At forty-seven, I felt as rootless as Id been as the newly minted college graduate who boarded a freighter bound for South America what seemed like several lifetimes ago. Since then, my career as a journalist had led me through wars and revolutions in Central America, the rise of criminal gangs in post-Soviet Russia, and most recently, the struggles of native tribes in places as far-flung as the Arctic, the Andes, and the Amazon, where indigenous people were manning the front lines against the advance of bulldozers and drill rigs that signaled the global economys final offensive on the planets shrinking pockets of primordial wilderness. It sounded incredibly romantic when I told people what I did for a living, especially since I usually glossed over the part about the failed marriage, the overdrawn checking account, and the guilt I felt about my three young boys, whom I didnt see nearly enough.