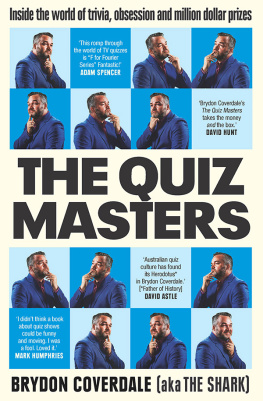

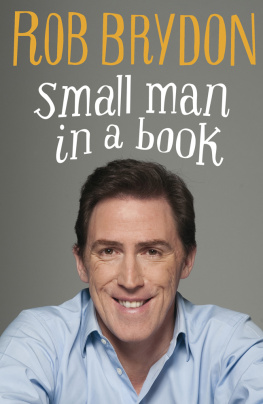

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Brydon Coverdale appeared on several quiz and game shows as a contestant, winning $300,000 on Million Dollar Minute before being cast as The Shark on Channel Sevens The Chase Australia, where contestants must beat Brydon to win their cash prize. He has also worked as a writer for pub trivia and currently writes a bylined daily quiz in the Herald Sun, the Daily Telegraph, The Courier Mail and The Advertiser, as well as a weekly quiz in one of Australias biggest rural newspapers, The Weekly Times. Away from quizzing, he spent eleven years as a cricket journalist for ESPNcricinfo, the worlds leading cricket website, travelling the world to cover Australias national team. He lives in Melbourne and is married with three children.

Copyright Brydon Coverdale, 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

pp. 196198: Grateful acknowledgement is given for permission to quote from A Thinking Reed by Barry Jones, copyright 2006. Used by permission of Allen & Unwin. All rights reserved.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone:(61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web:www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76106 550 7

eISBN 978 1 76106 388 6

Index by Puddingburn Publishing Services

Set by Bookhouse, Sydney

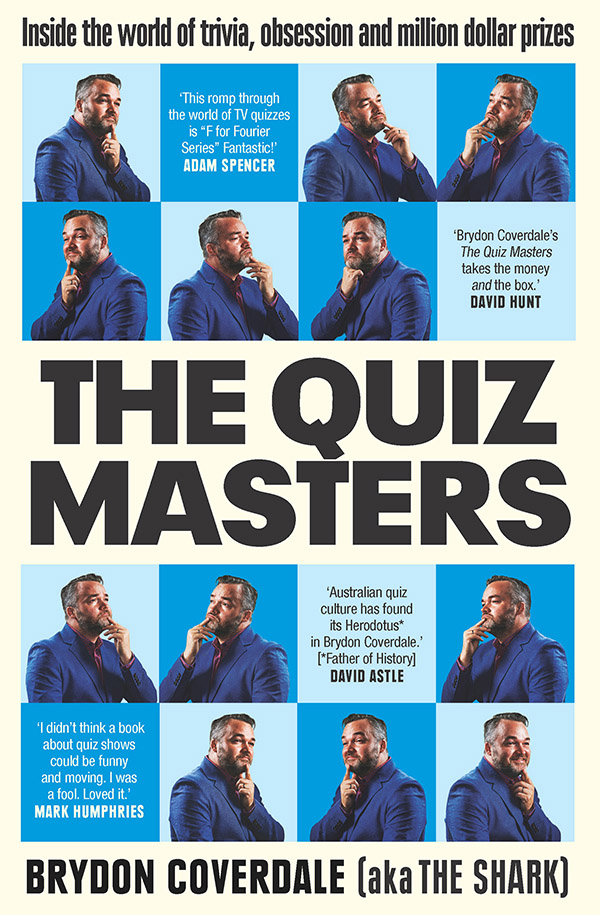

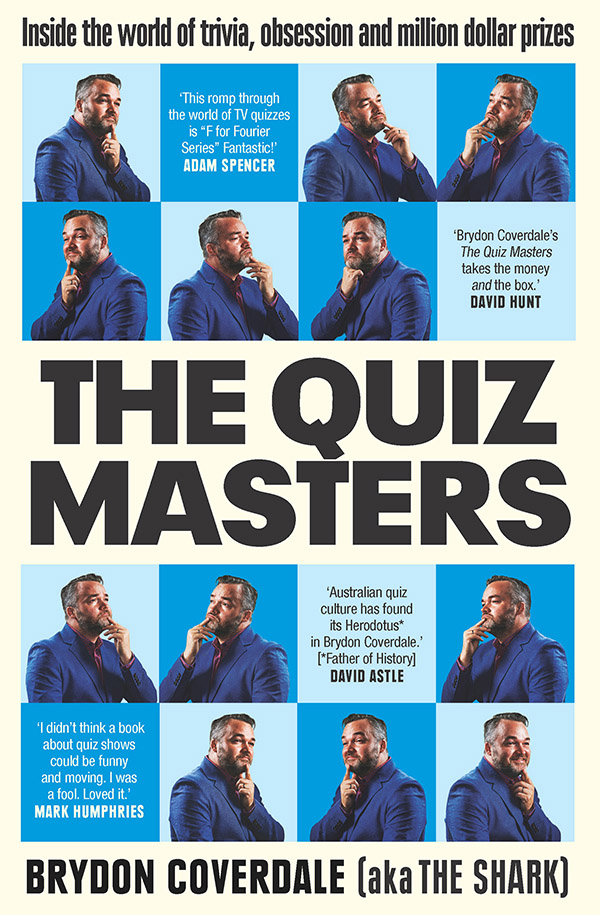

Cover design: Design by Committee

Front cover images: Fred Kroh

FOR ZOE, MY CARRY-OVER CHAMPION

AND FOR HEIDI, FLETCHER AND AVERY, OUR THREE MAJOR PRIZES

FOUR QUESTIONS. THIRTEEN SECONDS. FORTY-EIGHT THOUSAND DOLLARS. I can do this, but Ill have to be bloody fast. Come on, Brydon. Focus. Listen. Speed. Jump in when I can.

And your time restarts now.

The confectionery name nougat is from which (This must be about languages, I have to jump in and take the punt.)

Correct.

In which Sydney park is the Archibald Fountain? (Ugh, Im from Melbourne; guess whatever Sydney park I can name.)

Correct.

The film Darkest Hour stars Kristin Scott who? (Easy, theres only one actress with those names.)

Correct.

In which ocean is (Two seconds left, do I jump in and guess Pacific, its the biggest ocean with the most islands? No, I can spare one more second.) South Georgia Island? (Thank God I waited.)

Ooooohhh! Hes got it, team! Oh, team, it does not get closer than that! Im really sorry to say goodbye to that $48,000. You have been a terrific team

Four good, hard-working people have just seen their cash prize$12,000 eachvanish before their eyes. Had I stabbed at Centennial Park instead of Hyde Park, the money would have been theirs. If I had jumped in on the percentage guessthe Pacific Oceanfor the final question, they would have been laughing. Instead, their winnings have disappeared on a remote island in the South Atlantic. The contestants are devastated; I have done my job.

Perhaps running those two thoughts together is misleading. My job is not to devastate people, per se, but its a common side effect. As a chaser on the television quiz show The Chase Australia, my task is to stand between contestants and their prize money, to either beat them and stop them winning a cent, or to make them really earn their cash if they are good enough to defeat me. The role frequently leaves me with mixed feelings. Viewers may be surprised to learn that chasers even have feelings. Much like professional sportspeople, we are fiercely competitive and hate losing, but when we are beaten there is a silver lining: the ecstatic contestants on the winning team have just experienced the highlight of their year. It may even have been a life-changing moment. Good on them, I always think, while simultaneously kicking myself for not knowing what sport Ryan Broekhoff plays. The flip side is that, more often than not, the contestants go away disappointed, and I always feel for them. Why? Because Ive been there before. Many, many times.

Years ago, well before The Chase, I read the popular science book Outliers, in which the author Malcolm Gladwell analyses the factors that contribute to success. Gladwell makes frequent references to the 10,000-hour rule, the concept that virtually anyone can reach the elite level in any skill if they put in 10,000 hours of practice. I saw his examplesmusicians, sportspeople, entrepreneursand wondered why I had wasted my time doing a bit of this and a bit of that. I was a fairly good cricket writer, having spent a decade as a correspondent for ESPNcricinfo, but anyone who works in the same field for ten years should become an expert. Outside work, I was a jack-of-some-trades and master of none. It never occurred to me that quizzing was a skill that I had spent thousands of hours honingperhaps not 10,000, but well on the way. If that seems like a remarkable lack of self-awareness, I should explain that much of my quiz practice had taken place organically, over nearly three decades. When professional cricketers bat or bowl in the nets, they are clearly refining specific skills for an identifiable purpose. A pianist is obviously practising when they sit down at the piano. I didnt set out to become a professional quizzer. As far as I knew, no such job existed. But all those hours I came home from school and flicked through atlases and encyclopedias, memorised lists of prime ministers and capital cities, obsessively watched Sale of the Century and Who Wants To Be a Millionaire?, trained myself to go on those shows and win money, and wrote thousands of my own trivia questions, turned me into one.

Im often asked what got me so interested in trivia. The glib answer is that, as the youngest of four children, I was always trying to prove that I was just as good as my older siblings whenever we played Trivial Pursuit. There is some truth to that, but the real explanation is that I have always been intensely competitive at games and sports, and deeply curious about the world around me. Combine those two traits and what do you have? An obsession with quizzing, a sport for the brain.

Sometimes I wonder what my grandfather would make of my job. Ned Pollard, my mothers father, was a rugged Aussie bloke who grew up the eldest of eight children with not much money, fought in World War II and drove an Army truck that was blown up by a German mine in the North African desert, came home to a Soldier Settler block, cut down timber and split fence posts and built a dairy farm from scratch, lost a finger in a machinery accident, milked cows twice a day for most of his life and worked his body bloody hard until his heart gave up while he was carting hay in his late seventies. And here is his grandson sitting on his backside in an air-conditioned studio, in a tailored blue suit, hair slicked back like a sleazy Mob lawyer, showing off by recalling what famous singer launched the House of Dereon fashion label. I hardly know what to make of this absurd situation myself.

Next page