Contents

Guide

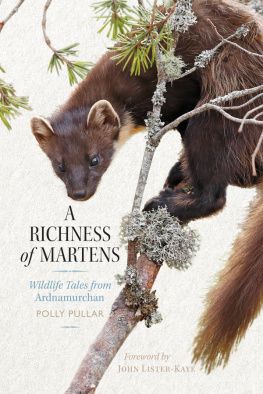

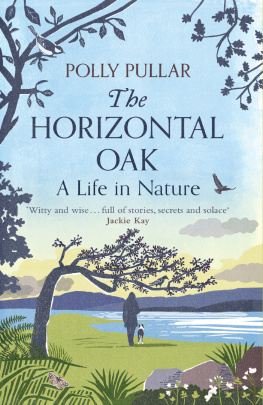

Polly Pullar is a field naturalist, writer and photographer who grew up in Ardnamurchan. She is also a wildlife rehabilitator. She contributes to a wide selection of magazines, including the Scottish Field, Peoples Friend, the Scots Magazine and BBC Wildlife. She is the author of a number of books including, A Drop in the Ocean: Lawrence MacEwen and the Isle of Muck, The Red Squirrel A Future in the Forest and co-author of Fauna Scotica: Animals and People in Scotland.

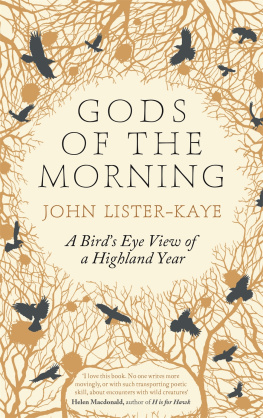

Sir John Lister-Kaye is an acclaimed naturalist, writer and lecturer who is also Director of the Aigas Field Centre in the Scottish Highlands. His books include Natures Child: Encounters with Wonders of the Natural World, At the Waters Edge: A Walk in the Wild and Gods of the Morning: A Birds Eye View of the Highland Year, which was awarded the inaugural Writers Prize by the Richard Jefferies Society in 2016.

First published in 2018 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

Copyright Polly Pullar 2018

Foreword copyright John Lister-Kaye 2018

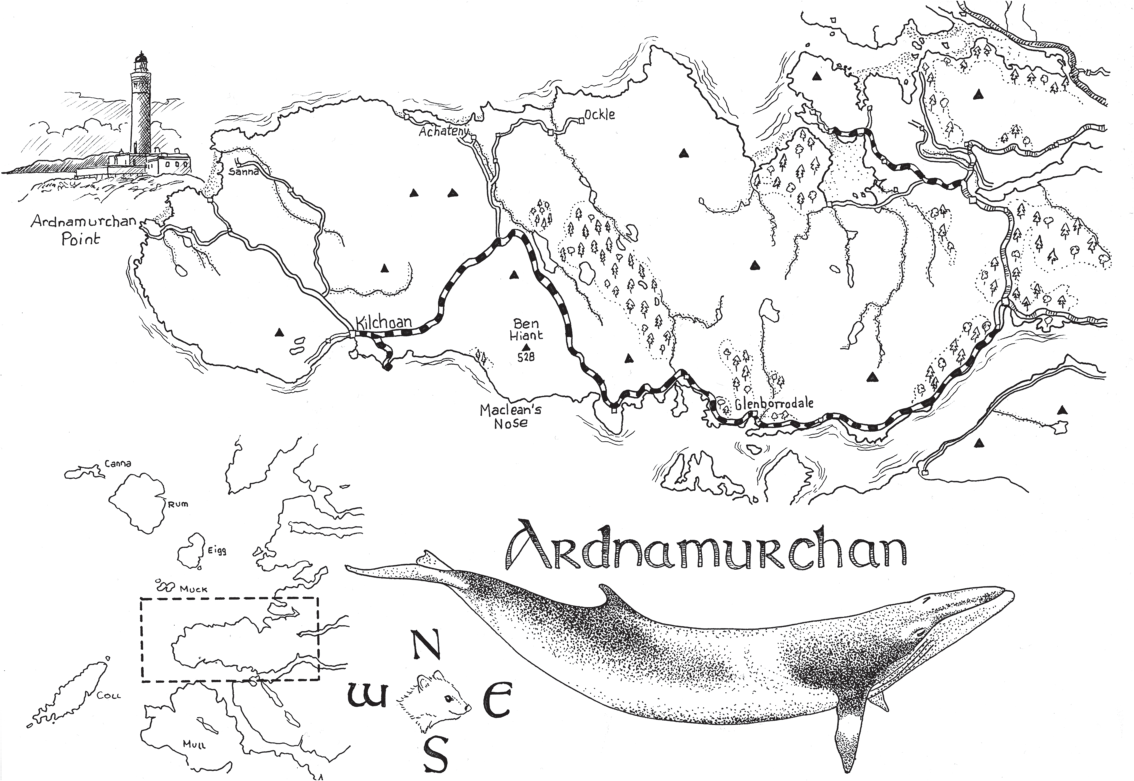

Line illustrations copyright Sharon Tingey 2018

ISBN 978 178885 070 4

The right of Polly Pullar to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Designed and typeset by Initial Typesetting Services, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by Gutenberg Press, Malta

For Freddy and Iomhair,

and Les and Chriss family Tim, Kathryn, Lizzie,

Chas and Struan

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

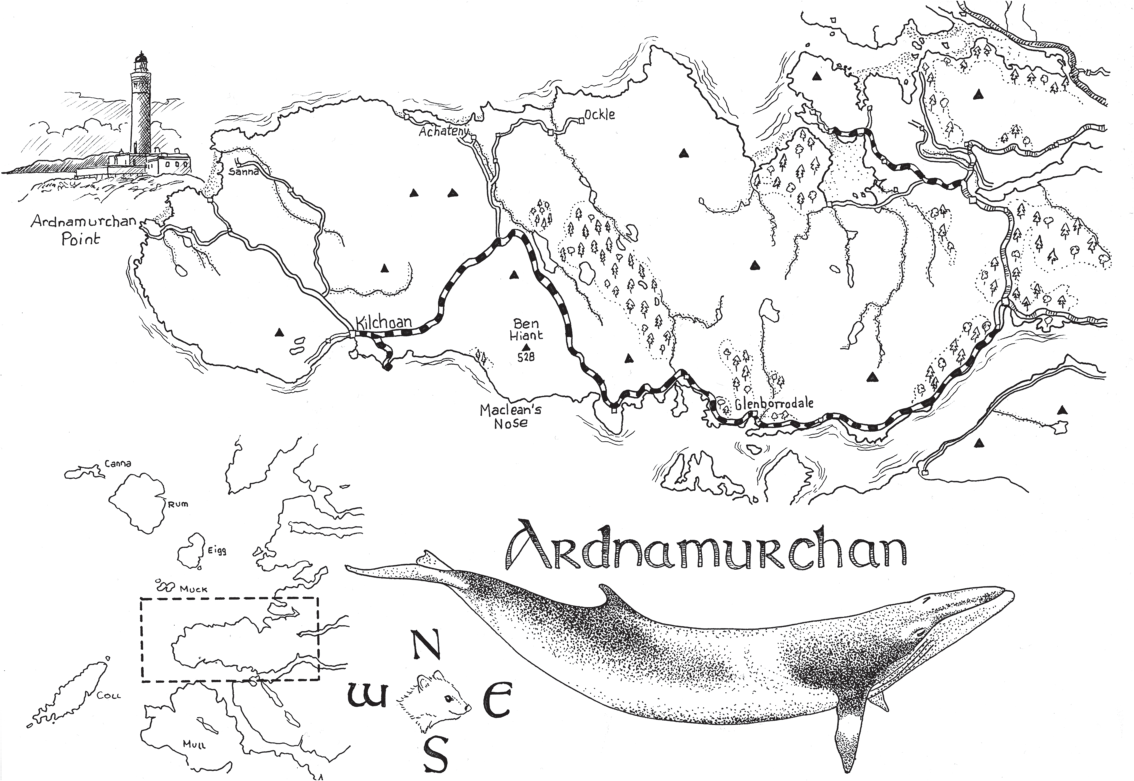

I would like to thank the many people who have helped me, both directly and indirectly, to write this book. Firstly, Sue and Dochie Cameron. Not only did Sue introduce me to Les and Chris Humphreys, but over many years she and Dochie have provided me (and the collies) with a wonderful haven where I can write in peace. I would also like to thank Dochie for lugging in a table on each of my visits to Ockle for use as an all-important desk, and both him and his brother Dougie for dealing with water, electrics and various other domestic snags caused by the weather, or the mice!

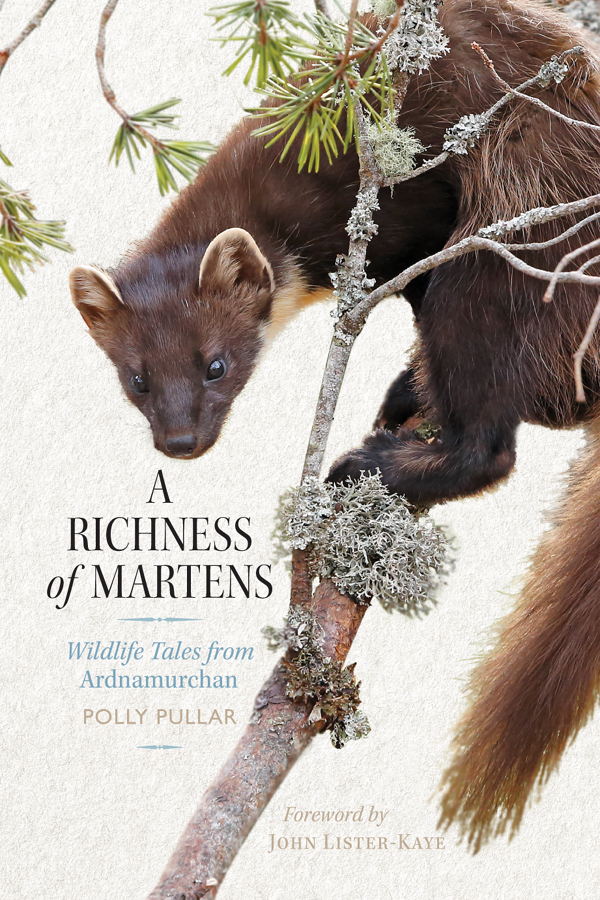

Thanks also to my son Freddy and my partner Iomhair for unstinting support and understanding. To John and Lucy Lister-Kaye, whose work at the world-renowned Aigas Field Centre provides constant inspiration, and in particular to John for the lovely piece he has written to open my story. To Sharon Tingey for her sensitive illustrations and patience with an ever-changing remit. To wildlife photographer Neil McIntyre for the books front cover photograph. To Rob and Becky Coope for their input and valuable friendship. To Jim Crumley, wildlife kindred spirit with whom I often discuss our shared concerns for the future of the natural world. To Colin Seddon and Romain Pizzi, whose tireless wildlife work is inspirational and makes so much difference. To magazine editors Angela Gilchrist, Robert Wight and Richard Bath for giving me endless scope to write about what I love best. To Evelyn Veitch, who cares so beautifully for our burgeoning menagerie during my absences from home. To Dr Debbie Shann, who will understand why. Special thanks to Kevin and Jayne Ramage, and Sally and Dorothy of the Watermill Bookshop, Aberfeldy, for continual support and enthusiasm with literary ventures various. Special thanks also to Andrew Simmons of Birlinn, who is always such a pleasure to work with, and copy-editor Helen Bleck, who has also been a joy as well as an invaluable help. And of course to my publisher, Hugh Andrew, and the rest of the team at Birlinn.

None of this would have come about without the extraordinary dedicated input and patience of Les and Chris Humphreys themselves, who have put up with endless queries and cajoling from me, and sifted through reams of video footage and diaries to confirm information. They have been delightful to work with, and I want to thank them for all they have done and for trusting me with their extraordinary story.

And, finally, Les and Chris would like to thank Sue and Dochie, and Liz and Sandy for all their help and support over the years.

Polly Pullar

May 2018

FOREWORD

The pine marten a personal view

There is blood on the snow

and a trickle of rowan berry juice

on his bib where the pine marten

stands for a moment like a man.

from The Pine Marten,

by David Wheatley

Just a memory now, fading but still there. That first glimpse, that splash down into realisation that such a creature still existed. Id like to be able to say that it was just so, in such-and-such a place, precise and named. A moment so electric and unforgettable that even after all these years I could still tell you when the year, the month, the day. Id like to boast that it spun me into instant awareness or understanding, or love or obsession, or something that its permanently branded. But no, Id be lying. It wasnt like that at all. It was a moment fogged with doubt, even disbelief could it be... ? Was that a... ? Have I just seen... or am I fooling myself? Perhaps it was a just a cat.

It was so rare back then, rarer than a wildcat and as rare a sighting as an osprey that now-much-cherished, cream and mocha fish-eagle gamekeepers had blasted to the brink of legend because ospreys had the temerity to eat salmon and trout. That was the way of things in those days, a relentless, focused persecution of any raptor and any carnivore, a tyranny almost never challenged. And no one seemed to care. The marten had gone the same way. After centuries of being hunted by Highlanders for their glossy, mink-like fur, when Victorian gentry refashioned the Scottish Highlands into a preserve for red deer, grouse and salmon, and gamekeepers were appointed as armed, over-zealous warlords to patrol and terrorise their vast upland estates, all predators were outlawed. Martens were poisoned, shot and taken with that most vicious of cruel weaponry, the tooth-jawed gin trap. A singular and determined extirpation was the only goal. That is why they became so rare. They were clinging on just by a claw and a whisker, and then only in the remotest mountain wilds.

So not so surprising that I couldnt believe my eyes, couldnt be sure that I had seen right. But it was. A furry dash across a twilit, single-track road somewhere up a glen and I cant even remember exactly which glen. And then nothing. It had vanished into an ocean of impenetrable broom and gorse. I stopped the car, reversed back, waited, got out, ran forward, ran back, willed it to show again. Nothing. It had gone. But I knew in the marrow of my bones that I had glimpsed one of Britains rarest mammals Martes martes, a pine marten, the most agile and beautiful of the British mustelids, the weasel family. That second-long sighting had hoiked it back from literary obscurity. No longer was it just a name on a page or a blurry photograph in a book, as remote and impersonal as an ad on a hoarding. I had seen it in the flesh for myself. It had lived and moved and, for the blink of an eye, it had shared with me its agile, lissom, Bournville being.