This book contains really stupid advice. Please dont follow it.

It was 1983. I was in Canberra for the weekend and my friend Philip was serving a meal. Hed bought himself a pasta machine and was creating spaghetti for four. The kitchen was in disarray. Hed used every pan in the house and splashed every wall with tomato sauce. As the mixture bubbled away, he discussed his latest passion. Hed discovered that certain wineries sold port in bulkpackaged in 12-litre plastic bladders which you then bottled yourself.

Philip rummaged around in his pantry then turned to face me, holding aloft two schooners of port. Herehave some, he exclaimed, pushing the glass into my hand.

I took the glass and studied it against the light. I didnt know port was meant to have a head, I said.

Take no notice, replied Phil. Its fresh from the bladder.

I hoped he meant a bladder of the plastic kind. I took a sip.

Tastes good, I lied.

He leant down conspiratorially. Actually, its a headache in a bottle. But at 20 cents a glass

Philip served up the meal and I helped him carry the bowls into the living room. Our girlfriends were sitting at the table, waiting to be fed. Gillian, Phils partner of a few years, studied history; Debra, my more recent girlfriend, was trying to make it as a playwright. The two liked nothing better than raving to each other about the books they were reading.

Philip swung back to the kitchen and returned with two more schooners, placing them with a flourish in front of the women.

Debra lifted her glass and held it against the light. I didnt know port was meant to have a head, she said.

Its fresh from the bladder, Phil repeated, with the tone of a proud sommelier.

We got stuck into the food and drink, and Philip and I joined the discussion. Neither of us had read the novel in question but, in this group, total ignorance did not appear a barrier to expressing a firm opinion. We drained our port schooners and Phil poured another round.

Phil had not only made the meal, hed also made the table at which we sat. It was beautifully constructed, from Huon pine, with a pale, silky surface. I was hardly a craftsman but even I could comprehend the skill involved in its dovetail joints and bevelled edges and I complimented Philip on his achievement. With his second port in hand, Phil enthused about the table, the art of woodwork and how he loved the feeling of making something with his hands.

He put on an LPone of the stack of Bob Dylan records he played almost constantlyand the four of us danced to the music. The women were wearing jeans and Indian cotton tops. I found them both spectacularly attractive. I wanted us all to be friends forever.

Philip and I decanted another bottle of port and managed to spill a good measure over our feet. Thats for later, I confided. Ill be able to suck that out of my boot on the way home.

I went back to dancing while Philip took a breather, sitting back at his handmade table, running his fingers idly over the surface. One day, he mused, Id like to build something bigger. A lot bigger. No, a LOT bigger. He wrapped his knuckles hard against the wood. Like a house, he added. We could just buy a block of land, you know, the four of us, and have a go.

I laughed. Well, snorted really. The girls laughed. The idea was absurd. We all ignored it and kept dancing.

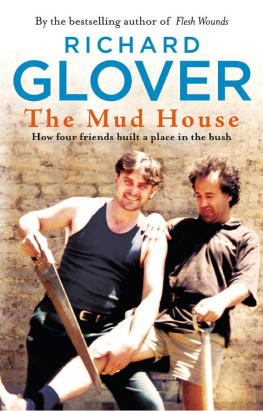

Six months later I was in a car, sitting beside Philip, bumping down a dirt track somewhere in the bush north of Sydney. We were trying to buy a block of rural land on which we could build a house from scratch, using our own labour. It was an absurd proposition. Even as I navigated down the bush track, I couldnt believe I had agreed to something so unlikely. I didnt have the skills to change a light bulb. I had trouble differentiating a chisel from a screwdriver. I had never used a circular saw. There was no way I could take part in building a house.

Philip was my best friend, but we were a study in opposites. He was stocky, with a barrel chest, dark skin and curly, black hair. At school hed been a champion weightlifter, and his body was still compact and muscly. He was a dedicated law student, but read fiction voraciouslysetting himself the challenge of reading every new Australian novel. He had a certainty about him, a self-confidence that I envied.

I was paler, thinner, more neurotic, my shoulders drooping apologetically forward like a letter r. I thought of myself as a bit frayed, as if I could unravel at any time. I found it hard to be in the moment; always feeling as if I was watching myself, and passing judgement on my own behaviour. It was as if my brain was not in my own body but perpetually hovering above ita mordant, blackhearted crow.

Id never been a practical, hands-on sort of guy; more the wan, bookish type. From the age of 12 or 13, my main hobby had been the local youth theatre club. Much of my adolescence had been spent lying on my back pretending I was a melting ice-cream, or running in circles, my arms flapping, embodying the spirit of the North Wind. (Youd have been impressed; I was the spitting image.)

At school they had tried, and failed, to make a man of me. Forced into the rugby union team, the coach would scream from the sidelines: Glover, pick up the ball, run with it.

Cant, sir, Id yell back. Might get hurt, sir.

At athletics theyd try to get me to jog with the others around the field. Well, Id say, since youll all be back so soon, would you mind terribly if I just waited here?

Id even scribbled ballet on my school sports formtaking advantage of a loophole which allowed boys to fulfil their sport commitments with out-of-school activities. The school authorities had in mind such manly pursuits as yachting, fencing and mountaineering, yet, for two terms, they let me off twice a week to attend the Belconnen Ballet Centre, where I produced some of the worst performances ever seen in the history of modern dance.

It is good to have a boy in the class, the teacher had observed, contemplating her troupe of 29 girls and one boy. But it would be marvellous if you were strong enough to lift your partner more than an inch off the ground.

At age 15, I even got into a serious schoolyard fight. Of course, it was over a novel. As I sat on the grass reading during lunch hour, some scoundrel stomped on my booka treasured copy of PG Wodehouses Right Ho, Jeeves. Dash it all, man, I protested, jumping to my feet. You cant step on another chaps book. In my choice of words, I may have been overly influenced by my reading material; the phrase dash it all was not particularly common in the mid-70s Australian schoolyard. It certainly brought a look of festive merriment into the eyes of the lad who, thus encouraged, was about to become my assailant.

If Id been reading Ernest Hemingway or Dashiell Hammett I may have won the bloody, scrappy fight that followed; instead, I had to take comfort that my reputation as a bookish weirdo had been confirmed.

The school doubled its efforts to make a man of me, forcing me to do a course in woodwork. In this class, tasks were allotted according to the skill level of the student. While my schoolmates built tongue-and-groove scale models of the Eiffel Tower, I busied myself with the breadboardthe optimistic name for the rectangle of wood given to the slow boys.

Its not that difficult, Glover.

Alas, sir, I find it so.

After a year of breadboard studies, they moved me on to more complex tasks, such as the pencil box with the slide-on lid. Here at least there was room to move. If the lid wouldnt fit into the groove first time, you could make the observation: It will loosen up over time. Then, when the teacher wasnt looking, you could approach it with a hammer and attempt to make it see reason.