INTRODUCTION

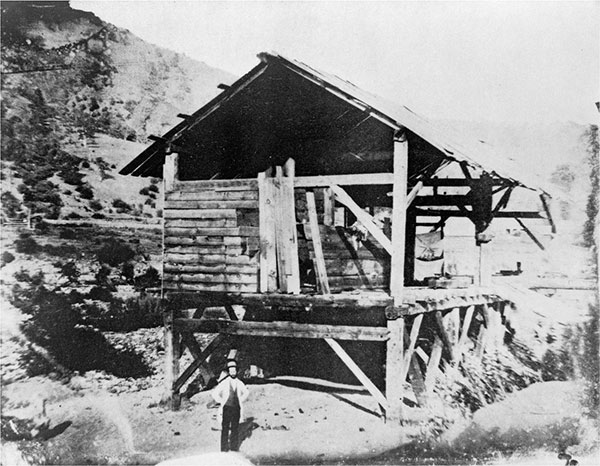

History is replete with stories of multiple disasters, both natural and artificial, that have not only brought death to the masses but also, many times, created panic and distrust among the public in general. On January 24, 1848, gold flakes were discovered by James Wilson Marshall at Sutters Mill in the American River near the base of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. This resulting rush, comprising mostly men eager to travel to California seeking gold, reached its heyday in 1849. By years end, the population of California was estimated to have increased by approximately eighty thousand over the total at the end of the previous year. Some three hundred thousand migrants came not only from the eastern and southern states but also from Latin America, Europe and even Australia. These forty-niners, as they were called, traveled any way that they could.

St. Louis, Missouri, quickly became a major travel hub for those traveling west overland. Due to its central location and large population, it became the last major port for the purchase of goods needed for the long journey. It was the gateway to the west. This rush for gold was relatively short-lived; by 1855, it reached its end.

This rush for gold paralleled another great migration already in progress: the continuing movement of members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from various parts of the country, and Europe, to the Salt Lake Valley. Even though some of the forty-niners followed much the same path the Latter-day Saints were traveling, many of them traveled together only from St. Louis, up the Missouri River, until they parted at such cities as St. Joseph, Independence and Westport, Missouri. Some even traveled the same route to Council Bluffs, Iowa, and on to the Salt Lake Valley. As St. Louis quickly became a gathering place for immigrants of the Church traveling to the Salt Lake Valley, William Clayton, in 1848, wrote The Latter-Day Saints Emigrants Guide to help those journeying west.

Photomechanical reproduction of an 1850(?) daguerreotype by R.H. Vance shows James Marshall standing in front of Sutters sawmill, Coloma, California, where he discovered gold. Printed 1948. Public Domain per Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Guidebooks told the immigrants what supplies they needed to bring in order to survive the months-long journey with few chances to resupply, what types of draft animals to buy, the locations of the best places to camp, and where dangerous places or routes existed. Claytons guide was so popular that non-Mormon immigrants also began to use it, and other publishers plagiarized it.

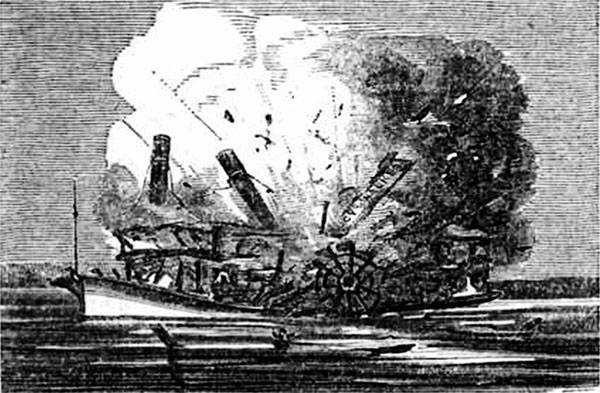

The Missouri River became the preferred route for anyone traveling to the western edges of this country. Unfortunately, river travel was not without its dangers. Steamships regularly sank or exploded on the journey from St. Louis to St. Joseph and beyond. One of the worst steamship explosions happened to the side-wheeler steamboat Saluda, the last hope for Mormons to make a quick departure to Council Bluffs, where they would catch a wagon train to Salt Lake Valley. On the morning of April 9, 1852, as the Saluda left Lexington, Missouri, its boilers exploded, disintegrating over half of the steamer.

The sound of the explosion was so loud that it was heard two miles away. Bodies, baggage and steamer parts were seen flying in all directions. Even the six-hundred-pound safe, along with the ships bell, landed high up on the bank. Those passengers in the lower, or forepart, of the steamer were the ones who died. Those on the deck, or the stern, were numbered among the survivors. At least 28 members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints lost their lives; at least as many were severely injured (there was no exact count of passengers on the boat). In addition to the members of the Church, who made up only about half of the passengers, an additional 47 passengers, along with most of the crew, perished in the\ explosion. Some reports indicated that upward of 135 persons lost their lives.

Luckily, the survivors found refuge and support from the citizens of Lexington. Not only were the travelers nursed back to health, but the locals also raised money for those who were left with nothing and helped find homes for the orphaned children.

Steamboat Saluda river explosion, March 1852. Westerntrips.blogspot.com.

It was this Missouri River, and these journeys, that brought a group of forty-niners and a group of members of the Church of Jesus Christ together in a most unfortunate situation. The deaths attributed to the sideboard steamship James Monroe tend to get overlooked in the discussion of steamship disasters, perhaps because the deaths were not attributed to a ships sinking or exploding, but to a cholera epidemic. Nonetheless, the loss of life was tremendous and is worthy of remembrance.

The story of the James Monroe was widely publicized in the newspapers of the day, with accounts appearing from New Orleans to Boston and in many large and small towns in between. This is a difficult story to accurately tell. Newspapers disagreed with each other, memories faded in later years, name spellings vary and even dates and places are sometimes incorrect. I am hopeful that I can accurately reconstruct the story of the cholera that afflicted so many individuals and families as they passed through the Jefferson City, Missouri area on that fateful day in May 1849.

The names of those who died and those who survived come from multiple sources. Some of the information about who they were has not been found; for others, I have tried my best to piece together their lives in an attempt to bring life to as many as I could. My apologies for what appears to be incorrect English usage or spellings, especially in some of the direct quotes. I have attempted to maintain the original text exactly as it was written.

E.S. Dils, one of the cholera survivors, put it best when he said, I think the horror of the Monroe has no parallel in the history of this country; perhaps not anywhere else.