Published by La Trobe University Press in conjunction with Black Inc.

Level 1, 221 Drummond Street

Carlton VIC 3053, Australia

www.blackincbooks.com

www.latrobeuniversitypress.com.au

La Trobe University plays an integral role in Australias public intellectual life, and is recognised globally for its research excellence and commitment to ideas and debate. La Trobe University Press publishes books of high intellectual quality, aimed at general readers. Titles range across the humanities and sciences, and are written by distinguished and innovative scholars. La Trobe University Press books are produced in conjunction with Black Inc., an independent Australian publishing house. The members of the LTUP Editorial Board are Vice-Chancellors Fellows Emeritus Professor Robert Manne and Dr Elizabeth Finkel, and Morry Schwartz and Chris Feik of Black Inc.

Copyright Barbara Minchinton 2021

Barbara Minchinton asserts her right to be known as the author of this work.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

9781760642419 (paperback)

9781743821886 (ebook)

Cover design by Regine Abos

Text design and typesetting by Dennis Grauel

Cover photo of Viennese sex worker (c. 1865) by Imagno / Getty Images

Author photo by Viv Mellina

Dedicated to all the sex workers who have ever suffered from stigma, shame or discrimination on account of their job

INTRODUCTION

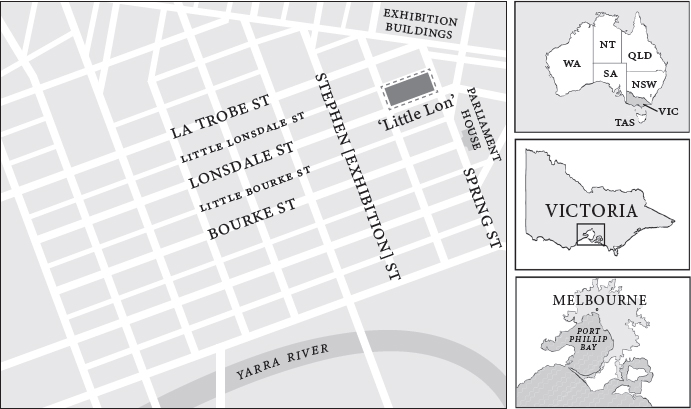

IN THE 1880S, LITTLE LON WAS MELBOURNES premier sex-work precinct. The name came from the narrow street at its core Little Lonsdale Street but the brothels were spread over a number of blocks, with the most expensive establishments located on the main streets and the cheaper ones in the back lanes. Little Lon was convenient to the men from parliament, the treasury and the government offices in the north-east corner of Melbournes street grid, and also to various entertainment venues, such as the theatres and the exhibition buildings. It housed hundreds of women employed at all levels of the industry. At a time when most working-class women were restricted to factory, shop or domestic work, and middle-class women were confined to home duties, sex workers were contributing a substantial amount to Melbournes economy.

The sex industry in Melbourne is alive and well today, but between the current industry and that of the nineteenth century, there is one important difference: all of the well-known brothels in Little Lon were run by women, and most of the women who werent working in the expensive establishments worked independently or with groups of friends. It was a female-dominated economy, and the women had far more autonomy than most respectable women of the time.

Touring nineteenth-century sex-work districts such as Little Lon is a common tourist excursion now, but questions like do you know any sex workers? or have you ever been in a brothel? can still be conversation stoppers. The stigma that was accorded to sex workers in the nineteenth century is still with us today, and as a result, the history of sex workers and brothels is largely told by uncritically repeating stories found in the nineteenth-century tabloid press.

Looking west down Little Lonsdale Street from Spring Street, 187075: many of these houses were brothels in the nineteenth century.

History as I know it should at least begin with facts, and then strive for truth and understanding, but tabloid history prefers titillation to truth, and values sales above respect for its subjects, breathing sensationalism and the colourful language of denigration. It tells stories without checking the facts, allowing Madame Brussels, Melbournes most famous brothel owner, to be given the wrong maiden name, and her smooth-talking enemies to be quoted without their lies being challenged. Even the modern-day Madame Brussells Tour of Little Lon spells her name wrong. People misspelled it in her own day, too, but back then it was a matter of poor education, not poor history. Women like Madame Brussels deserve better.

As a history of sex work in nineteenth-century Melbourne, this book aims to dismantle the myths and counter misinformation and deliberate distortions about the sex workers. It begins from the premise that womens lives matter, and pleads for less tabloid history and more respect for female historical figures in general. The #MeToo movement has shown how women are silenced, and their experiences are suppressed and ridiculed. This matters in history as much as in Hollywood. Too many historical female figures have been treated as badly as contemporary ones especially women who ran brothels or sold sex for a living.

Location of Little Lon, in inner-city Melbourne

#MeToo has revealed some of the mechanisms of power that have been used against women, but every industry has its unique patterns, and within those patterns every woman has her own story. By telling the stories of individual women in Melbournes nineteenth-century sex industry, I hope to heighten understanding of and respect for the lives of all sex workers. And by using more life histories and fewer coy labels like women of unstated, but no doubt ancient, occupation (as one Melbourne historian described them), I hope to restore at least some dignity to the historical women of the sex industry and reduce the stigma attached to the work today.how unworthy the individuals may have appeared to others in their own time, by understanding the conditions of their lives, we understand more about the world around them, and more about where our own social attitudes have come from.

This book is divided into four sections. The first section describes and explains the legal and social setting for the provision of sexual services in Victoria in the nineteenth century, including how the business worked and how it was able to thrive in a cultural framework that paradoxically disapproved of yet enabled it. Sex work was not technically illegal for most of the nineteenth century, but it was not considered respectable or acceptable either, so it lived in a kind of half-light, where its violent and criminal elements were regularly reported in the newspapers and the rest was left in the shadows. It is here that the power of men and their attitudes towards women can be seen in action: in parliament and the police force, and in the pulpits and newspapers, the men who circumscribed womens opportunities in life condemned those women who then made what respectable people regarded as poor choices. At the same time, the business of sex work was tolerated in the community because it generated profits for all sorts of other businesses, which then had a vested interest in keeping the industry going. The experiences of historical sex workers are used throughout these chapters as examples.

The second section describes sex workers as a group: how many were there, where were they born, what kind of backgrounds did they have? It describes their child-bearing histories and their methods of contraception, the risks they faced in terms of sexually transmitted infections and abortion. It then introduces some of the other people who lived in Little Lon. How did the sex workers fit into the broader community? Were they regarded as wicked women or unfortunate victims of circumstance? Were they seen as entrepreneurs or outcasts? By examining some of the practical day-to-day situations they faced, we can gain a more nuanced picture of the possibilities and choices that were available to them.