Pagebreaks of the print version

SECRET AGENDA

Watergate, Deep Throat, and the CIA

Jim Hougan

As Ever: For Carolyn, Daisy and Matt;

For Michael Salzberg;

Necnon Diaboli Advocato: R.D.L.

I had this nagging feeling that the Watergate might turn out like the Reichstag fire. You know, forty years from now will people still be asking did the guy set it and was he a German or was he just a crazy Dutchman?

Howard Simons, Washington Post

We witness an attempted coup detat of the U.S. government through well-measured steps by a non-elected coalition of power groups.

Bruce Herschensohn, Nixon aide

Special thanks should be extended to Robert Fink and Jeffrey Goldberg for their research assistance and patient criticism.

Introduction

In the early morning hours of June 17, 1972, five men were arrested in the Watergate headquarters of the Democratic National Committee (DNC). Wearing business suits and surgical gloves, they were in possession of bugging devices and photographic equipment.

Within twenty-four hours, police and FBI agents established links between the arrested men, the Committee to Re-elect the President (CRP) and the Nixon White House. In the meantime a political cover-up had already begun: evidence was shredded and burned, perjury contemplated, and justice obstructed by some of the most important officials in the U.S. government. Despite this, and despite the administrations efforts to depict the break-in as a third-rate burglary unworthy of attention, the story stuck tenaciously to the front pages of liberal newspapers throughout the United States. During that summer and fall, the press, and in particular the Washington Post, pursued the issue in an effort to learn the extent and nature of the administrations dirty tricks, and the identities of those responsible for them.

As the Presidents reelection neared, it became increasingly difficult for those involved to stonewall the press. An employee of one of the arrested men told the FBI that he had monitored some two hundred telephone calls emanating from the DNC, which, he claimed, had been bugged for the first time in May of 1972. With the guidance of an anonymous source, nicknamed Deep Throat, Washington Post reporters rattled the White House with a barrage of front-page articles about secret campaign funds, vicious campaign practices and much more. Soon a Senate select committee was convened to explore the affair, and one of the first witnesses that it heard was a former CIA officer named James McCord. A turncoat in the eyes of his accomplices, McCord was one of the men arrested in the Watergate. Infuriated by the Nixon administrations handling of the affair, and fearful of receiving a draconian sentence, McCord had written a letter to the judge who presided over the criminal case against the original defendants. In that letter, McCord wrote that perjury had been committed, that there were other conspirators who were yet to be named, and that political pressure had been applied to ensure the silence of those under arrest. McCord promised to tell all, and soon afterward so did White House officials such as John Dean. Finally, after a succession of damaging revelations and the enforced resignation of subordinates, the President was hoisted by his own petard: the existence of a secret White House taping system was revealed and, with it, Nixons complicity in the cover-up. On August 8, 1974, he announced his resignation as President of the United States.

Public reaction to that announcement was a mixture of jubilation (on the part of Nixons enemies) and relief (on the part of his friends). For nearly two years the country had been blitzed by the minutiae of Watergate and force-fed the images of increasingly uninteresting men. Was there anyone left who did not consider himself a reluctant expert on the subject? Probably not.

It is against some odds, therefore, that ten years after the affair has been put to rest I offer the reader a new book on what has already been the subject of more than a hundred and fifty books. That I do so is partly the result of an accident. I had intended to write not a book about the Watergate affair but a magazine profile of a private detective named Louis J. Russell. An alcoholic and a womanizer, Russell had been one of the countrys foremost Red hunters during the 1950s while a top staff member of the House Committee on Un-American Activities (the notorious HUAC). In researching the sordid details of Russells life, I soon learned of his employment by McCord and, what is more, of his presence at the Watergate break-in on the night of the arrests. In an attempt to understand what he was doing there on that momentous evening, I studied the break-in with more attentiveness than the authorities themselves had displayed a decade earlier. Because the burglars had been caught in the act, the burglary itself had not seemed to warrant intensive investigation. The best efforts of the press, the Senate and subsequently the special prosecutor were therefore applied to questions of political responsibility and culpability in the cover-up. For that reason, many questions about the break-in had been left unanswerednot the least of which was its purpose.

Eventually I was able to answer some of these questions by interviewing men and women whose evidence had been ignored. These were not, for the most part, White House officials or Cabinet members but lowly workers at the DNC, waitresses and maintenance men at the Watergate, landladies, secretaries, cops, neighbors, desk clerks and security guards. The details they provided led to a picture of the Watergate break-in that was far different from what had been transmitted via television at the time.

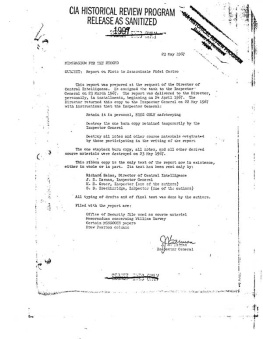

Besides these interviews, I was able to obtain (through the Freedom of Information Act) literally thousands of pages of FBI documents pertaining to Watergate. These included interviews, laboratory reports, summaries, chronologies, air-tels, photographs and telephone records. Most of this materialindeed almost all of itwas never available to the Senates Ervin committee. An internal memorandum of the FBI states that [T]he only information we furnish to that Committee is the opportunity to review FD-302S of interviews conducted during the McCord investigation. Such FD-302s must be specified by the name of the person interviewed and are made available only for review, not copying. In effect, the FBI investigation of the Watergate affair was off-limits, except on the most restricted basis, to the very committee that sat in judgment of the Nixon administration. Clearly, the Senates conclusionsand American historywould have been radically different if the bureaus findings had been shared more freely at the time.

I was the first outsider, then, to get an inside look at the FBIs Watergate investigation, and what I found was startling. The most fundamental premise of the affair has always been that White House spies bugged the Democrats in their headquarters at the Watergate complexapparently to gain political intelligence. FBI documents, however, and other evidence that was either ignored or overlooked by Senate committees, prosecutors and the press show conclusively that: