The Great Rebuildings of Tudor and Stuart England

The Great Rebuildings of Tudor and Stuart England

Revolutions in architectural taste

Colin Platt

University of Southampton

(c) Colin Platt, 1994

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

First published in 1994 by Routledge

Reprinted 2004

by Routledge,

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Transferred to Digital Printing 2005

The name of Routledge is a registered trade mark used by Routledge with the consent of the owner.

ISBN:

1-85728-315-5 HB

1-85728-316-3 PB

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Platt, Colin.

The great rebuildings of Tudor and Stuart England : revolutions in architectural taste / Colin Platt.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-85728-315-5 (HB) : $65.00. ISBN 1-85728-316-3 (PB) $21.95

1. Architecture, DomesticEngland. 2. Architecture. RenaissanceEngland. 3. Architecture, Modern17th, 18th centuriesEngland. I. Title.

NA965.P83 1994

728.094209081dc20

94-32050

CIP

Typeset in Bembo.

Contents

T he Great Rebuilding of Tudor and Stuart England, as Professor Hoskins first described it, has not survived the test of later criticism. And it has long been clear that a one-off Great Rebuilding, however generously defined, never happened. Even the term Great Rebuilding can be seriously misleading, for it focuses too much attention on a capriciously surviving housing stock, to the loss of other evidence of changing tastes. Yet the fact remains that the disposable wealth of English property-holders of every known degree from the gentry and nobility of Lawrence Stones well-known books to the more modest yeomen farmers of Hoskinss seminal article was rising very rapidly during Elizabeths reign, and that the quality of their housing rose with it. Hoskins used a broad brush. But those widespread contemporary improvements to which his study drew attention the flooring-over of medieval open halls, the insertion of stairs and chimneys, the glazing of windows and the accumulation of household goods all commonly happened when he said they did, between 1570 and 1640. If something looks like a duck and sounds like a duck, common sense dictates, it probably is a duck. By that measure at least, Professor Hoskinss original Great Rebuilding is still persuasive.

Hoskins never wrote about a second Great Rebuilding. Instead, he stopped his own Rebuilding when the Civil War began, and clearly viewed that costly struggle as a watershed. So indeed it proved to be for the many formerly prosperous landowning families who had built before the war, but who found themselves impoverished by the conflict. Those were the post-war rebuilders, unable to afford better, who turned most readily to new-style compact boxes as a remedy. Even so, it was less the Civil War which promoted such developments than the reopening of continental Europe to English travellers. He that will know much out of this great Book, the World, must read much in it, wrote Richard Lassels, author of a popular Voyage of Italy (1670). The urban terrace, the compact villa and the double-pile house each the direct ancestor of houses we build today were all learnt abroad by Grand Tour travellers.

Travel abroad would certainly have meant less, had it not been for changing attitudes in the homeland. Traditional hospitality, already on the wane in late-medieval England, continued its decline throughout this period. The once extended English family became nuclear. But while social historians have long debated these changes, very few have looked to architecture as a source. Their neglect is my opportunity. To quote Lassels again: Well; if others have written upon this subject, why may not I? They did the best they could, I believe: but they drew not up the Ladder after them.

It was Roger North who once said that he that hath no relish of the grandure and joy of building is a stupid ox. On change, he was equally direct. Here ended the antique order of housing, said North of his youth, writing of the reign of Charles II. It was a half-truth only, restricted to gentry-builders such as himself. And the new order of housing, which North announced, took its time trickling downwards through the classes. Nevertheless, the way we live now has more in common with the life-style of Roger Norths generation than he himself admitted sharing with his father. It was the second Great Rebuilding, far more than the first, which departed from the past and broke new ground.

I also break new ground in giving special prominence to that Rebuilding in my book. But I owe an obvious debt to earlier writers on this subject, not least to Professor Hoskins who began it all. Another debt is to John Harris, whose collected contemporary views of English country houses, in The artist and the country house (1985), taught me more about the expectations of Restoration gentry-builders than any written source save Roger North. My third debt is to Claire Donovan, who gave me Harriss book with so much else.

Southampton 1994

The First Great Rebuilding

Then down with old houses and new set in their places

W hen W. G. Hoskins, back in 1953, identified a revolution in housing in late Tudor and Stuart England, calling it the Great Rebuilding, he found general support for his thesis. Indeed, the material evidence of an improved housing stock from the reign of Elizabeth I is still there for everybody to see. But like many of the most significant historical insights R. H. Tawneys precisely contemporary rise of the gentry was another And that, with reservations, remains the case.

Most of those reservations concern individual localities, where major rebuildings occurred both earlier and later than Hoskinss model. In parts of rural Wales, for example, substantial late-medieval farmhouses required little remodelling until the mid-seventeenth century at the earliest.

Plainly, an accumulated surplus on the land was what enabled remodellings to take place. But that was never the only reason for new building. Indeed, so individual were the circumstances of even major rebuildings, occurring at so many different periods, that one of the most effective critics of the single Great Rebuilding thesis has counselled its abandonment altogether. Instead of a thesis of a Great Rebuilding at some specific period, Machin wrote in 1977, we require a theory of building history which will explain (with regional variations in timing) the medieval preference for impermanent building, the emergence of permanent vernacular building in the fifteenth century, its extension and the successive rebuildings of vernacular houses from the late sixteenth to the early eighteenth century, and the replacement of vernacular by polite or pattern-book architecture from the mid-eighteenth century. No solid achievement nor lasting worth promoted the rebuilding of Elizabethan Southampton, as insubstantial as a paradise of fools.

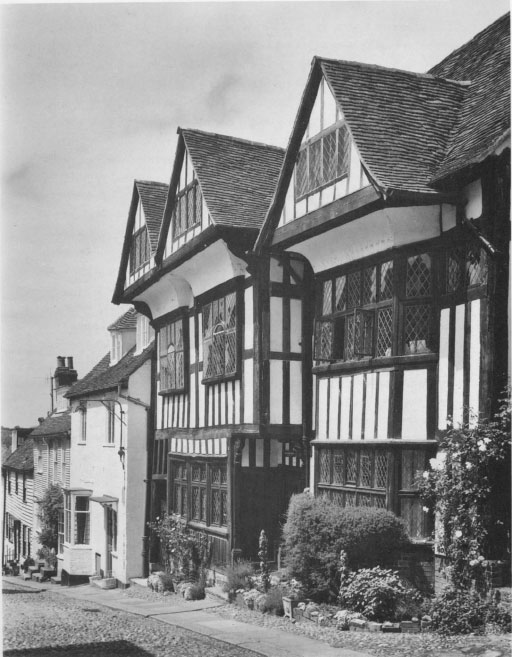

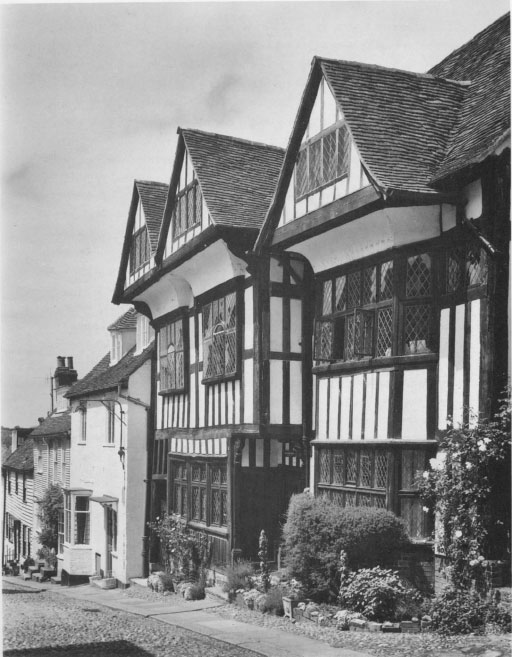

Dated 1576, this substantial merchants house in Mermaid Street (Rye) is typical of many Elizabethan rebuildings in towns all over the country, for the houses where the fathers dwelt could not content their children.