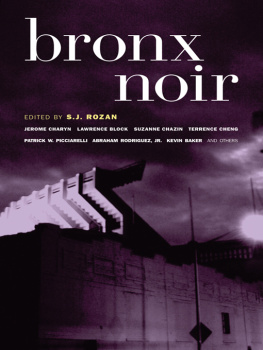

Winter and Night

S. J. Rozan

ST. MARTIN'S MINOTAUR

New York

www.ebookyes.com

WINTER AND NIGHT. Copyright 2002 by S. J. Rozan. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address St. Martin's Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

www.minotaurbooks.com

ISBN 0-312-70434-8

Also by S. J. Rozan

China Trade

Concourse

Mandarin Plaid

No Colder Place

A Bitter Feast

Stone Quarry

Reflecting the Sky

acknowledgments

Three cheers for:

Steve Axelrod, my agent

Keith Kahla, my editor

MVPs

Steve Blier, Hillary Brown, Monty Freeman, Max Rudin,

Jim Russell, and Amy Schatz

All-stars

Betsy Harding, Royal Huber, Barbara Martin,

Jamie Scott, and Keith Snyder

Coaches

Kim Dougherty, Corey Doviak, Pat Picciarelli,

and the team at Manhattan Sports Medicine

Trainers

NeverTooLate Basketball and the SKW Laser Beams

Teammates

David Dubal

for continuing education

Carl Stein

the car guy

Deborah Peters and Nancy Ennis

the home team

Helen Hester

traded to New Orleans

Peter Quijano

for the circus catch

and DL and GP

for raising the bar

Then come home my children

The Sun has gone down

The dews of evening arise.

Your spring and your day

Are wasted in play

Your winter and night in disguise.

William Blake, Songs of Experience

One

When the phone rang I was asleep, and I was dreaming.

Alone in the shadowed corridors of an unfamiliar place, I heard, ahead, boisterous shouts, cheering. In the light, in the distance, figures moved with a fluid, purposeful grace. Cold fear followed me, something from the dark. I tried to call to the crowd ahead: my voice was weak, almost silent, but they stopped at the sound of it. Then, because the language I was speaking wasn't theirs, they turned their backs, took up their game again. The floor began to slant uphill, and my legs were leaden. I struggled to reach the others, called again, this time with no sound at all. A door swung shut in front of me, and I was trapped, longing before, fear behind, in the dark, alone.

* * *

The ringing tore through the dream; it went on awhile and I grabbed up the phone before I was fully awake. "Smith," I said, and my heart pounded because my voice was weak and I thought they couldn't hear me.

But there was an answer. "Bill Smith? Private investigator, Forty-seven Laight Street?"

I rubbed my eyes, looked at the clock. Nearly two-thirty. I coughed, said, "Yeah. Who the hell are you?" I groped by the bed for my cigarettes.

"Sorry about the hour. Detective Bert Hagstrom, Midtown South. You awake?"

I got a match to a cigarette, took in smoke, coughed again. My head cleared. "Yeah. Yeah, okay. What's up?"

"I got a kid here. Fourteen, maybe fifteen. Says he knows you."

"Who is he?"

"Won't say. No ID. Rolled a drunk on Thirty-third Street just up the block from two uniformed officers in a patrol car."

"Sounds pretty stupid."

"Green, I'd say. Young and big. I told him what happens to kids like him if we send them to Rikers."

"If he's fourteen, he's too young for Rikers."

"He doesn't know that. He's been stonewalling since they brought him in. Two hours I been shoveling it on about Rikers, finally he gives up your name. How about coming down here and giving us some help?"

Smoke twisted from the red tip of my cigarette, lost itself in the empty darkness. A November chill had invaded the room while I slept.

"Yeah," I said, throwing off the blanket. "Sure. Just put it in my file, I got out of bed at two in the morning as a favor to the NYPD."

"I've seen your file," Hagstrom said. "It won't help."

* * *

Fragments of stories I would never know appeared out of the night, receded again as the cab took me north. Two streetwalkers, one white, one black, both tall and thin, laughing uproariously together; a dented truck, no markings at all, rolling silently downtown; a basement door that opened and closed with no one going in or out. I sipped burnt coffee from a paper cup, watched fallen leaves and discarded scraps jump in the gutters as we drove by. The cab driver was African and his radio kept up a soft, unbroken stream of talk, words I couldn't understand. A few times he chuckled, so whatever was going on must have been funny. He let me out at the chipped stone steps of Midtown South. I overtipped him; I was thinking what it must be like to grow up in a sun-scorched African village and find yourself driving a cab through the night streets of New York.

Inside, the desk sergeant directed me through the glaring fluorescent lights and across the scuffed vinyl tile to the second floor, the detective squad room. Two men sat at steel desks, one on the phone, the other typing. A third man, at the room's far end, punched buttons on an unresponsive microwave.

"Ah, fuck this thing," the button-puncher said without rancor, trying another combination. "It's fucked."

"You break it again?" The typist, a bald-headed black man, spoke without looking up.

"Hagstrom?" I asked from the doorway.

The guy at the microwave turned, said, "Me. You're Smith?"

I nodded. He was a big, sloppy man in a pretty bad suit. He didn't have a lot of hair but what he had needed a trim. "You know how to work these things?" he asked me.

"Try fast forward."

The typist snorted.

"Screw it," Hagstrom said, abandoning the microwave, crossing the room with a long, loose-jointed stride. "Doctor says I should lay off the burritos anyway. Come with me."

I followed him into the corridor, around a corner, into a small, stale-smelling room. It was empty and dim. The only light came from the one-way mirror between this room and the next, where a big kid rested his head on his arms at a scarred and battered table. Two Coke cans, an empty Fritos bag, and a Ring Ding wrapper littered the tabletop.

Hagstrom flicked a switch, activated the speaker. "Sit up," he said.

The kid's head jerked up and he looked around, blinking. His dark hair was short; he wore jeans, sneakers, a maroon-and-white varsity jacket with lettering I couldn't make out on the back. They were all filthy. He rubbed a grubby hand down his face, squinted at the glass. That glass is carefully made: It will show you your own reflection, tell you what's behind you; it hides everything else.

Hagstrom switched the speaker off again. "Know him?"

"Yeah."

Hagstrom waited. "And?"

"Gary Russell," I said. "He's fifteen. Last I heard he lived in Sarasota, but that was a couple of years ago. What's he doing here?"

"You tell me."

"I don't know."

"What's he to you?"

I watched Gary shift uncomfortably in the folding chair they had him on. The knuckles on his left hand were skinned; his jacket had a rip in the sleeve. The dirt on his face didn't hide the bags under his eyes or the exhausted pallor of his skin. As he moved, his hand brushed the Fritos bag, knocked it to the floor. Conscientiously, automatically, he picked it up. I wondered how long it had been since he'd had real food.

"He's my sister's son," I said.

This small room was too close, too warm, nothing like the crisp fall night the cab had driven through. I unzipped my jacket, took out a cigarette. Hagstrom didn't stop me.

"Your sister's son, but you're not sure where he lives?" Hagstrom's eyes were on me. Mine were on Gary.

"We don't talk much."

Hagstrom held his stare a moment longer. "You want to talk to him?"

I nodded. He stepped into the corridor, pointed to a door a few feet away. He backed off, so that I was the only thing Gary saw when I opened the door.

Next page