Ralph D. Paine

Chapter I.

The World-Wide Hunt for Vanished Riches

The language has no more boldly romantic words than pirate and galleon and the dullest imagination is apt to be kindled by any plausible dream of finding their lost treasures hidden on lonely beach or tropic key, or sunk fathoms deep in salt water. In the preface of that rare and exceedingly diverting volume, "The Pirates' Own Book," the unnamed author sums up the matter with so much gusto and with so gorgeously appetizing a flavor that he is worth quoting to this extent:

"With the name of pirate is also associated ideas of rich plunder, caskets of buried jewels, chests of gold ingots, bags of outlandish coins, secreted in lonely, out of the way places, or buried about the wild shores of rivers and unexplored sea coasts, near rocks and trees bearing mysterious marks indicating where the treasure was hid. And as it is his invariable practice to secrete and bury his booty, and from the perilous life he leads, being often killed or captured, he can never revisit the spot again, therefore immense sums remain buried in those places and are irrevocably lost. Search is often made by persons who labor in anticipation of throwing up with their spade and pickaxe, gold bars, diamond crosses sparkling amongst the dirt, bags of golden doubloons and chests wedged close with moidores, ducats and pearls; but although great treasures lie hid in this way, it seldom happens that any is recovered."

In this tamed, prosaic age of ours, treasure-seeking might seem to be the peculiar province of fiction, but the fact is that expeditions are fitting out every little while, and mysterious schooners flitting from many ports, lured by grimy, tattered charts presumed to show where the hoards were hidden, or steering their courses by nothing more tangible than legend and surmise. As the Kidd tradition survives along the Atlantic coast, so on divers shores of other seas persist the same kind of wild tales, the more convincing of which are strikingly alike in that the lone survivor of the red-handed crew, having somehow escaped the hanging, shooting, or drowning that he handsomely merited, preserved a chart showing where the treasure had been hid. Unable to return to the place, he gave the parchment to some friend or shipmate, this dramatic transfer usually happening as a death-bed ceremony. The recipient, after digging in vain and heartily damning the departed pirate for his misleading landmarks and bearings, handed the chart down to the next generation.

It will be readily perceived that this is the stock motive of almost all buried treasure fiction, the trademark of a certain brand of adventure story, but it is really more entertaining to know that such charts and records exist and are made use of by the expeditions of the present day. Opportunity knocks at the door. He who would gamble in shares of such a speculation may find sun-burned, tarry gentlemen, from Seattle to Singapore, and from Capetown to New Zealand, eager to whisper curious information of charts and sailing directions, and to make sail and away.

Some of them are still seeking booty lost on Cocos Island off the coast of Costa Rica where a dozen expeditions have futilely sweated and dug; others have cast anchor in harbors of Guam and the Carolines; while as you run from Aden to Vladivostock, sailormen are never done with spinning yarns of treasure buried by the pirates of the Indian Ocean and the China Sea. Out from Callao the treasure hunters fare to Clipperton Island, or the Gallapagos group where the buccaneers with Dampier and Davis used to careen their ships, and from Valparaiso many an expedition has found its way to Juan Fernandez and Magellan Straits. The topsails of these salty argonauts have been sighted in recent years off the Salvages to the southward of Madeira where two millions of Spanish gold were buried in chests, and pick and shovel have been busy on rocky Trinidad in the South Atlantic which conceals vast stores of plate and jewels left there by pirates who looted the galleons of Lima.

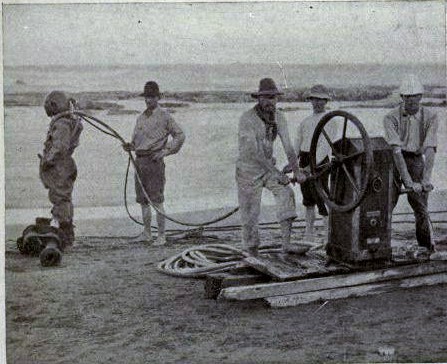

Near Cape Vidal, on the coast of Zululand, lies the wreck of the notorious sailing vessel Dorothea, in whose hold is treasure to the amount of two million dollars in gold bars concealed beneath a flooring of cement. It was believed for some time that the ill-fated Dorothea was fleeing with the fortune of Oom Paul Kruger on board when she was cast ashore. The evidence goes to show, however, that certain officials of the Transvaal Government, before the Boer War, issued permits to several lawless adventurers, allowing them to engage in buying stolen gold from the mines. This illicit traffic flourished largely, and so successful was this particular combination that a ship was bought, the Ernestine, and after being overhauled and renamed the Dorothea, she secretly shipped the treasure on board in Delagoa Bay.

It was only the other day that a party of restless young Americans sailed in the old racing yacht Mayflower bound out to seek the wreck of a treasure galleon on the coast of Jamaica. Their vessel was dismasted and abandoned at sea, and they had all the adventure they yearned for. One of them, Roger Derby of Boston, of a family famed for its deep-water mariners in the olden times, ingenuously confessed some time later, and here you have the spirit of the true treasure-seeker:

"I am afraid that there is no information accessible in documentary or printed form of the wreck that we investigated a year ago. Most of it is hearsay, and when we went down there on a second trip after losing the Mayflower, we found little to prove that a galleon had been lost, barring some old cannon, flint rock ballast, and square iron bolts. We found absolutely no gold."

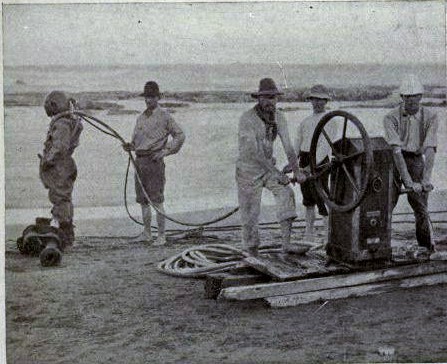

Treasure-seekers' Camp at Cape Vidal on African coast.

Divers searching wreck of Treasure ship Dorothea, Cape Vidal, Africa.

The coast of Madagascar, once haunted by free-booters who plundered the rich East Indiamen, is still ransacked by treasure seekers, and American soldiers in the Philippines indefatigably excavate the landscape of Luzon in the hope of finding the hoard of Spanish gold buried by the Chinese mandarin Chan Lu Suey in the eighteenth century. Every island of the West Indies and port of the Spanish Main abounds in legends of the mighty sea rogues whose hard fate it was to be laid by the heels before they could squander the gold that had been won with cutlass, boarding pike and carronade.

The spirit of true adventure lives in the soul of the treasure hunter. The odds may be a thousand to one that he will unearth a solitary doubloon, yet he is lured to undertake the most prodigious exertions by the keen zest of the game itself. The English novelist, George R. Sims, once expressed this state of mind very exactly. "Respectable citizens, tired of the melancholy sameness of a drab existence, cannot take to crape masks, dark lanterns, silent matches, and rope ladders, but they can all be off to a pirate island and search for treasure and return laden or empty without a stain upon their characters. I know a fine old pirate who sings a good song and has treasure islands at his fingers' ends. I think I can get together a band of adventurers, middle-aged men of established reputation in whom the public would have confidence, who would be only too glad to enjoy a year's romance."