This edition is published by Papamoa Press www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books papamoapress@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1960 under the same title.

Papamoa Press 2018, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

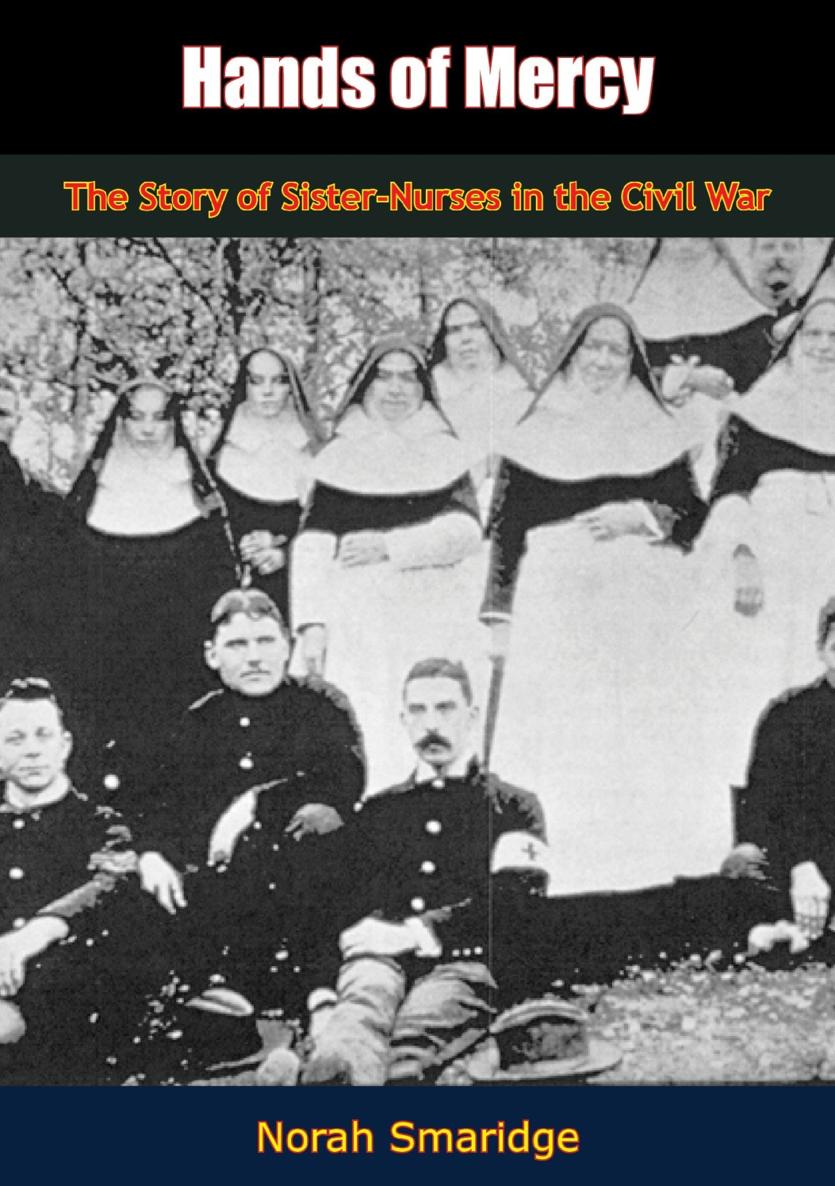

HANDS OF MERCY

THE STORY OF SISTER-NURSES IN THE CIVIL WAR

BY

NORAH SMARIDGE

Illustrated by ALBERT MICALE

Chapter ICARE OF THE SICK AND WOUNDED

WHEN THE FIRST SHOT WAS FIRED AT FORT Sumter in April, 1861, it started a civil war in which the staggering total of a million men were to die of wounds or disease. There were native Americans and foreign-born; Yankees and Johnny Rebs; white men and Negroes; seasoned fightersand brave little drummer boys.

In the beginning of the war, scant provision was made for the sick and wounded. There was no Red Cross organization at work in America; Clara Barton, the stalwart New Englander who made herself a one-woman relief agency on the battlefields of the Civil War, did not succeed in starting a branch until ten years after the end of the conflict. There were no first-aid stations, no field hospitals, and only a scattering of chaplains to minister to the dying.

Conditions in the army medical service were not much better than they had been during the Revolutionary War, eighty years earlier. There were some skilled surgeons, but trained nurses did not exist. Transportation was slow, therefore drugs and supplies were seldom at hand when needed. Anesthetics were in very short supply in both North and South, so operations were frequently performed while the patient was conscious. For the most part, these meant amputations; one surgeon, serving in a hospital on Spotsylvania field, wrote to his wife that he had operated steadily for four days and two nights, yet there are a hundred cases of amputations waiting. Poor fellows come and beg me almost on their knees for the first chance to have an arm taken off. It is a scene of horror such as I never saw.

The filth of the camps bred epidemics that ran unchecked. Even sponges and bandages carried infection, and wounds that first aid would cure today were then open invitations to death, for Joseph Lister had not yet introduced the antiseptics which have saved so many surgical patients lives.

Very early in the war, civil authorities and church officials faced the problem of caring for vast numbers of wounded and disabled soldiers. Knowing that the most pressing need was for nurses, the women of both sides rushed to help. Before the first battle was over, female volunteers from all parts of the land offered their services to the generals of the North and of the South.

The first offers came from laywomen. Wives, mothers, sisters and sweethearts of the soldiers, they were full of enthusiasm, but untrained and inexperienced. Removing the hoops from their billowing skirts, they tied on their bonnets, and simply went from their homes into the army camps.

Not all were allowed to remain. Officials sent the younger women home, and many others were unable to bear the hardships they encountered. Of the gallant, dogged women who stayed, some were rugged individualists like Mother Bickerdyke, who worked in the camps without the backing of any organization. The majority joined the Army Nursing Corps established by Dorothea Dix, or worked for one of the two great commissions, the Sanitary Commission and the Christian Commission.

Both these commissions sent their workers to camps, hospitals and transport ships all over the North. Each commission had its heroines, women like Mary Livermore and Katharine Wormeley, whose enterprise and daring filled America with admiration.

Thanks to their love of letter-writing and their habit of making lengthy entries in their diaries, these women left intimate and detailed records behind them. We know their names, and the nicknames given to them by the soldiers: Mary Safford, the little angel of Cairo; Mrs. Annie Etheredge, whom the boys called Gentle Annie; Bridget Devon, the wiry little Irish nurse known as Irish Biddyand many others.

We know even the homey details of what they ate and how they slept. Cornelia Hancock, a pretty Quakeress, wrote home: I am black as an Indian and dirty as a pig. I eat onions, cucumbers, potatoes, anything that comes along...and can go steadily from half-past six in the morning until ten oclock at night. Katharine Wormeley, a fashionable young lady from Newport, told her mother how useful she found her twin flasks of brandy and water in nursing the sick. They do good service. We wear them slung round our shoulders on a bit of ribbon, or at the end of a rope. Louisa May Alcott, later the author of Little Women , described the food which the nurses were served for dinner: beef evidently put down by the men of 76; pork, just from the street; stewed blackberries like stewed cockroaches.

No wonder that we are familiar with our heroic lay heroines of the Civil War. Their story has been told and retold for generations.

But there was another great army of women about whom far less is knownthe Catholic Sisterhoods who sent hundreds of nurses into hospitals, camps and transport vessels. The record which they left behind is a meager one. On the field, as in the convent, the Sisters practiced self-denial. Not for them the consolation of writing home. At most, the Sisters wrote impersonal reports to their Superiors. A few, under obedience, kept simple journals for the convent archives. Many of their names will never be known.

Often the Sisters went to battlefields and hospitals in answer to emergency calls from officials of the Northern or Southern armies. In the flurry of departure, their names were not entered upon the community records. While in service, they often changed from camp to camp; this, too, may account for missing names.

In carrying out their work, the Sisters were following a long tradition; their vocation was based directly upon the teaching of Christ. In pre-Christian times, there was little general understanding of the necessity of charity toward ones neighbor. Few in the great pagan world felt obliged to help their fellow man. In Sparta, for instance, frail or handicapped infants were simply abandoned, or left to be devoured by wild beasts.

In Roman homes, the sick were tended by slaves, or by the women of the household. But though the Romans did their best for their nearest and dearest, they were totally indifferent to the afflicted outside their own families. They did not even feel responsible for their slaves. When a slave fell ill, he was taken to the temple and left to the tender mercies of Aesculapius, the god of medicine.