This book has been published with the assistance of the

Drs. Ben and A. Jess Shenson Professorship.

Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

2010 by Charlotte DeCroes Jacobs. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

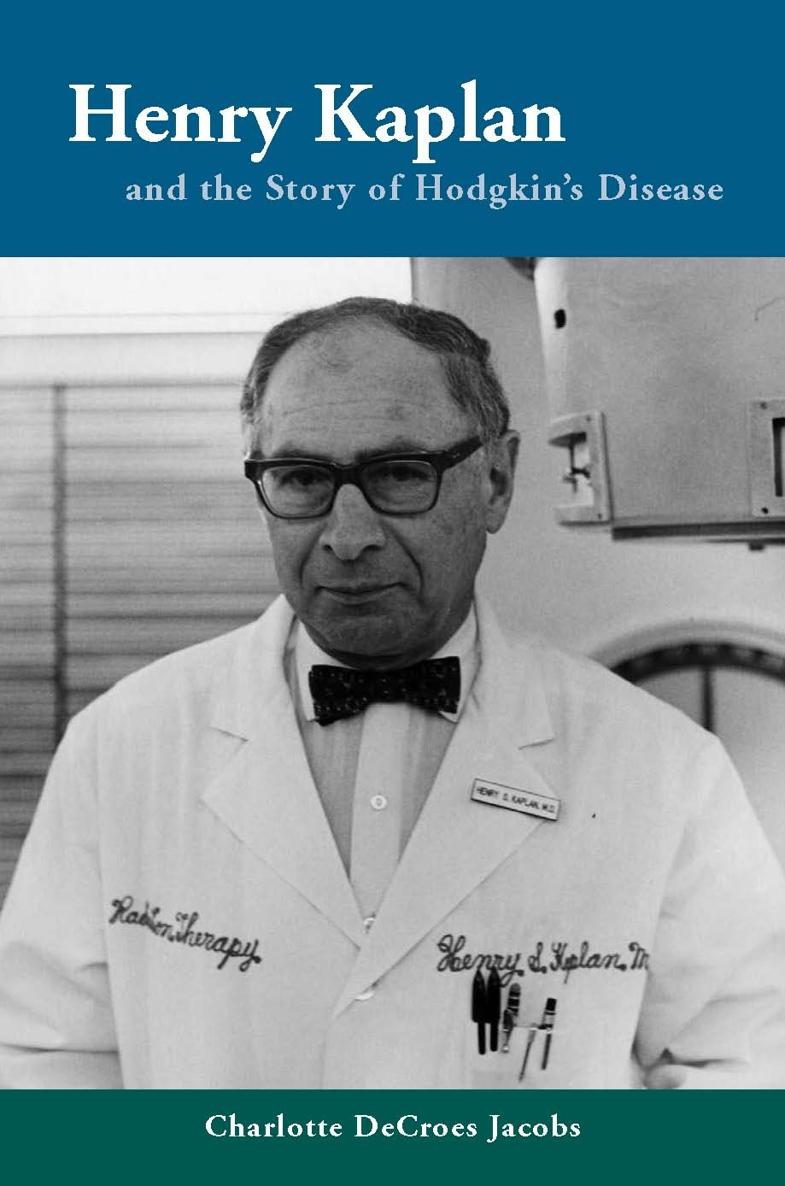

Jacobs, Charlotte DeCroes.

Henry Kaplan and the story of Hodgkins disease / Charlotte DeCroes Jacobs.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

9780804774482

1. Kaplan, Henry S., 19181984. 2. RadiologistsUnitedStatesBiography. 3. OncologistsUnited StatesBiography. 4. Hodgkins diseaseRadiotherapyUnited StatesHistory. 5. CancerTreatmentUnited StatesHistory. I. Title.

R154.K235J33 2010

362.196994460092dc22

[B]

2009040649

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper.

Typeset at Stanford University Press in 10/13 Minion.

Acknowledgments

How fortunate I have been to study writing for over a decade with a masterEhud Havazelet. He taught me the craft of and instilled into me a passion for writing, which has enriched my life. It is to him that I dedicate this book.

I am grateful to the late Leah Kaplan, who agreed to a biography of her husband, but only if I would portray the man as he was, not a saint. She spent hours with me, relating his life with honesty and humor. She opened her home, her personal files, and her heart. Paul Kaplan recounted family stories with candor and the exquisite detail of an artist. Ann Kaplan Spears, Richard Kaplan, and the rest of the Kaplan family provided thoughtful reminiscences.

When I sought my first literary agent, I started at the top, writing to Robert Lescher. Mickey Choate, formerly at Lescher & Lescher, Ltd., initially embraced my work and brought it to Roberts attention. To my amazement and delight, Robert Lescher accepted my biography with an enthusiasm that has never waned. I will be forever grateful for his wisdom, confidence, and friendship.

The late Dr. Ben Shenson and Dr. A. Jess Shenson gave me one of the greatest giftsthat of academic freedomwhen they endowed the Stanford University professorship I am privileged to hold. I appreciate how Ronald Levy, chief of Medical Oncology, never questioned the projects time or value. The Vermont Studio Center and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts provided the solitude and creative atmosphere for writing. John Feneron, Norris Pope, and the publishing team at Stanford University Press guided the book to its completion. Peter Dreyer, the copy editor, smoothed the rough edges and taught me how to use the delete button.

My thanks to all those who spent hours sharing their memories of Henry Kaplan. Each story, each letter gave me insight into this multifaceted man. I am especially appreciative of Vincent DeVita, Saul Rosenberg, Norman Coleman, and the late Vera Peters, for whom many of these memories were bittersweet. Spyros Andreopoulos kindly gave me a copy of his interview with Kaplan just prior to his death. My thanks to Todd Wasserman, who interviewed Sir David Smithers and provided photographs and encouragement. Several people read sections of the manuscript for accuracy: Jacob Haimson helped me understand the history and physics of linear accelerators, and Ron Levy examined the description of monoclonal antibodies. Margaret Wootton and my husband, Rod Young, read the entire manuscript from the lay perspective, making valuable suggestions.

I am grateful to the patients and families who welcomed me into their homes and their lives, especially Chris Jenkins and Tran Tuyet, Mary Murray Vidal, Wendy Podwalny, Douglas Eads, Christine Pendleton, and Annuziata Radicchi. And my eternal gratitude goes to the hundreds of patients with Hodgkins disease who participated in clinical trials and who, through that courageous choice, are responsible for the high cure rate today.

Many friends sustained me through the years of research and writing, including Lucy Berman, Linda Ara, and Ellen King. Writers Mary Dilg, Ruth Roach Pierson, and Emilie and John Osborn lent their moral support. And I owe special thanks to Sarah Donaldson, whose exuberance has persisted at the highest level. Finally, I turn to my family. My love and gratitude goes to my sons, Ben and Adam Elkin, who remained supportive and patient through the years. And I am blessed with a caring, selfless husband, Rod, the proverbial wind beneath my wings.

Prologue

HODGKINS DISEASE SURVIVORS GATHER AT STANFORD TO CELEBRATE GOOD HEALTH

At 38, Doug Eads is the picture of health. He is Fremonts city clerkan active, articulate man who loves to romp with his two young children, jog, ski the Sierras and race around on a racquetball court. If Eads had been born five years sooner, he wouldnt be around to enjoy all that. Hed be dead. In 1965, Eads noticed a small lump in his groin. A doctor told him it was Hodgkins disease, a cancer of the lymphatic system that would kill him in three to five years. But at the Stanford University Medical Center... scientists were trying some new treatments involving irradiation and drugs. Eads became a patient in the Stanford clinical trials.... They worked, and Eads has been free of the disease for the last 17 years. Today he and 400 other Hodgkins patients who were treatedand curedin the trials at Stanford in the last 20 years will gather at the university to celebrate their health and the success of the program. The patients meet once more with Henry S. Kaplan and Saul Rosenberg, the two doctors who directed the bold treatment and research effort.

San Jose Mercury News , May 8, 1982

The fountains in front of Stanford University Medical Center had just been switched on, and a family of ducks glided across the reflecting pool. Sunlight, filtering through the lattice trim, gave the hospital a lacy faade. Asparagus ferns dangled from hanging baskets; a medical student rode by on his bicycle. As Maureen OHara walked toward Fairchild Auditorium, she felt out of place in her silky dress and heels; it was the first time in years that she hadnt worn a nurses uniform to the hospital. Her face looked freshly scrubbed, with soft freckles scattered across her cheeks. Her loose brown hair bounced as she walked. Maureen didnt know what to expect. When she had received an invitation to Twenty Years of Research and Progress in the Treatment of Hodgkins Disease, she had thought it would be wonderful to see some of her former patients. She hadnt anticipated the scene she was about to encounter.

Over four hundred people filled the auditoriumwomen straight from their hairdressers, men and children in their Sunday best. The atmosphere felt festive. Spirited conversations were punctuated by noisy outbursts, resembling a high school reunion, a wedding, a graduation. Smiles and handshakes gave way to cheers and hugs. A woman in a cashmere sweater rushed forward and threw her arms around Maureen. It took a few seconds for Maureen to recognize her. Eight years earlier, she had lain in a hospital bed, her body limp from repeated vomiting, while Maureen held her hand. Now she hugged Maureen with great strength.