Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Fred P. Stashower (19021994) and David L. Stashower (19292018).

Something to fill that untidy gap on the second shelf.

For about three years, beginning in 1936, Eliot Ness kept tabs on my grandfather Fred P. Stashower. According to information in Nesss possession, Fred P. Stashower was an old egg-tossing vandal. This, I admit, was news to me.

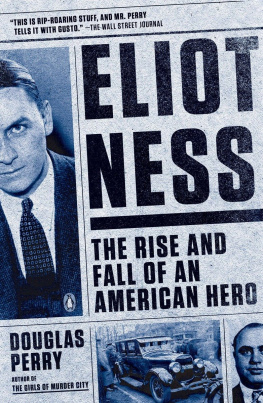

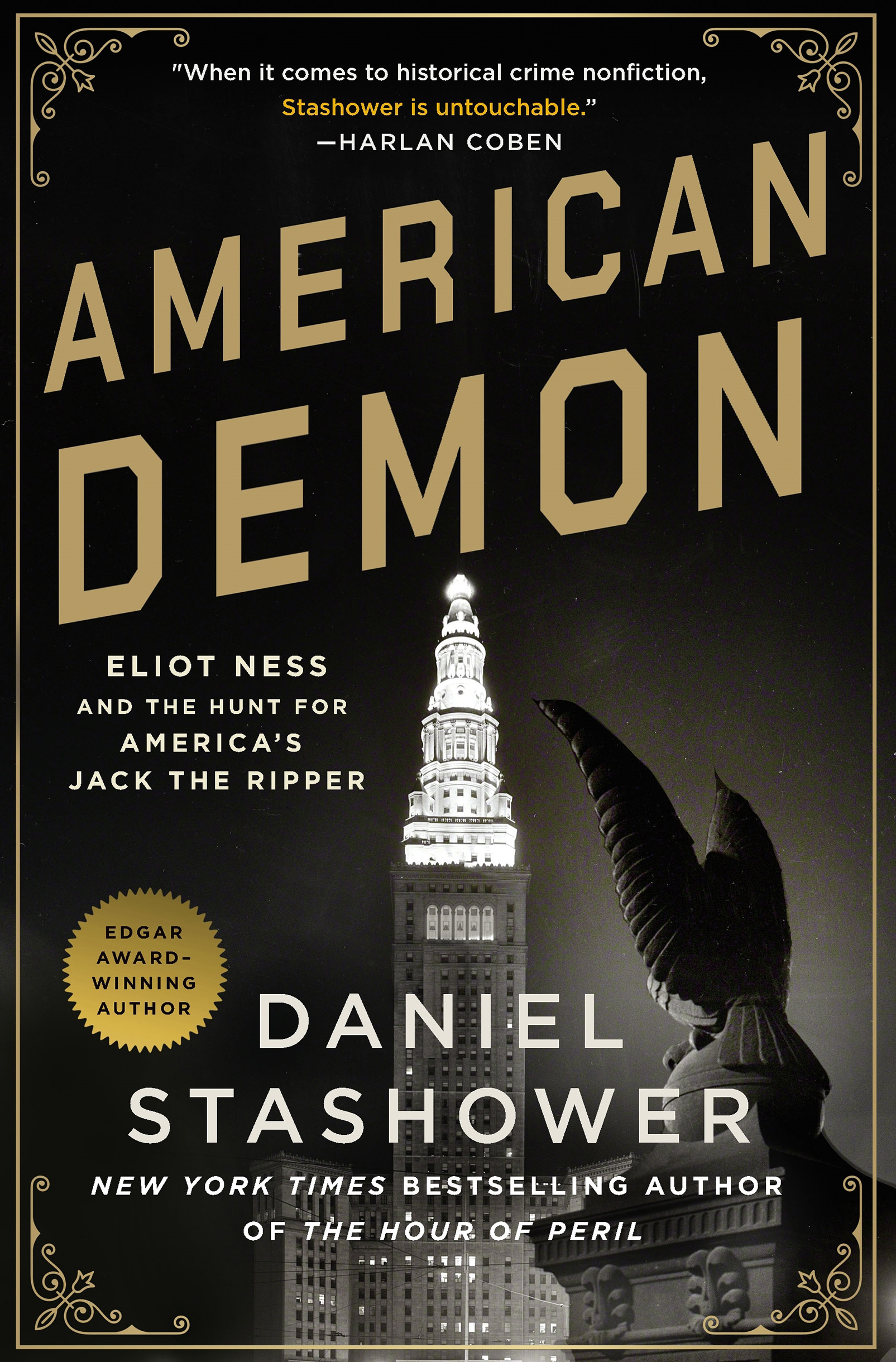

Eliot Ness, who rose to fame during the Prohibition era as the man who got Al Capone, kept tabs on a lot of people. His private papers, now preserved at Clevelands Western Reserve Historical Society, feature a rogues gallery of bootleggers, rumrunners, racketeers, and gangsters of all stripes. Scrapbooks from his Chicago days chronicle his storied career as the leader of the Untouchables, the legendary team of Prohibition agents who smashed up Al Capones illicit breweries. Eight Agents Caught Capone, reads one clipping. Eliot Ness, On the Spot, Escaped Death. There are also images of their famous battering-ram truck, rigged up with a heavy steel prow to crash through the doors of the alky kitchens that fueled Capones multimillion-dollar empire. Theres even a newspaper artists rendering of an enraged Capone swinging a baseball bat over his head, preparing to crack open the skull of a mob turncoat.

Still, as I flipped ahead in the scrapbooks, it became clear that the Untouchables formed a surprisingly narrow slice of Nesss career. Were often told that there are no second acts in American lives, but Ness, whose career in Chicago ended at the age of twenty-eight, badly needed one. He found it, after a couple of years in the wilderness, as director of public safety in Cleveland, a position that placed him in charge of the police, fire, and building departments of Americas seventh largest city. Most of the veteran policemen were cynical and didnt believe Ness was for real, one local reporter would recall. The politicians of both parties were sure he was an overpublicized tyro, a Boy Scout built up by the newspapers, who would soon fall on his face.

There was reason to think so. Ness was the youngest safety director in the history of any large city, and he arrived in Cleveland at a particularly turbulent moment. The city had been an industrial powerhouse in the 1920s, but all progress halted as the effects of the Great Depression took hold. Cleveland coasted downhill at dizzying speed, a city historian would note.

Worse yet, the Depression created a vacuum in which the underworld thrived. During the Prohibition years, Cleveland became a major hub of bootleg liquor and its sinister offshoots, including high-stakes gambling, prostitution, and racketeering. This, in turn, gave rise to a web of graft that ran through every level of the citys government and police force. Things got so bad, according to Clayton Fritchey of the Cleveland Press, that policemen were expected to tip their hats when they passed a gangster on the streets.

From his first day on the job, Clevelands new top cop chipped away at an entrenched system of bribes and payoffs. Ness took an aggressive, hands-on approach, insisting that he would not be a remote director, chained to a desk at city hall. I am going to be out, he said, and Ill cover this town pretty well. Not only that, he promised, I will do undercover work to obtain my own evidence and acquaint myself personally with conditions.

In truth, the odds of Ness going undercover were slim. His face appeared on the front pages of the citys newspapers almost daily, making him easily one of the most recognizable figures in town. In case anyone missed the photos, reporters were quick to embellish, often dwelling on his boyish good looks. He is about 5 feet 11 inches tall, weighs 172 pounds, has a mop of unruly brown hair which he futilely attempts to keep parted, the Press observed. His eyes are blue and keen and his complexion ruddy. He is trim and athletic. He looks more like a collegian than an expert criminologist.

His looks were deceiving. Day after day, for months at a time, Clevelanders awoke to read of some fresh feat of derring-do from their young safety director. Ness had kicked open the doors of an after-hours gambling parlor while the city slept, or cracked down on an extortion racket, or rousted a crooked precinct captain. There was never anybody like him, said one admirer. He really captured the imagination of the public in his early years, and he was given a heros worship.

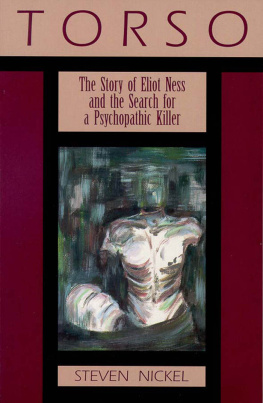

But there was one stubborn blot on his otherwise flawless record. Beginning in 1934, and continuing on Nesss watch, a string of brutal murders staggered the city. The killings were utterly without precedentso grisly and shocking that they came to be called a real-life Murders in the Rue Morgue. Though Cleveland had seen more than its share of violent crime, being nearly as mobbed up as Chicago and New York, these murders were chillingly exceptional. Each of the victims had been beheadedsome, it appeared, while still alive. The remains, in most cases, were painstakingly dismembered and scattered across the city.

The horror took many forms. A pair of schoolboys would stumble over a headless torso, or a hacked-off section of an arm or a leg would be spotted floating down the Cuyahoga River, or a severed head would appear in a city dump. Each atrocity touched off a fresh cycle of fear, outrage, and calls for action, with thunderous headlines such as The Mad Butcher Strikes Again and Who Is This Mad Torso Killer? Fifty years earlier, the entire world had recoiled as a series of horrific crimes unfolded in Londons Whitechapel district. Now, it seemed, an unnervingly similar note of terror had been struck in America. Clevelands Torso Killer, read one national headline, Slays in Same Manner as Jack the Ripper.

There were many parallels, certainly, but also troubling inconsistencies that posed a challenge to investigators. No pattern could be seen in the tally of the deadthere were men and women, blacks and whites, straights and gays. The victims, when they could be identified at all, were found to be indigents, drifters, or prostitutespeople who would not be missed. Some were known to have been living rough in the hobo jungles of Kingsbury Run, a dried-up riverbed that cut across the citys southeast side. This gloomy no-mans-landa patchwork of trash heaps, cooking fires, and pools of industrial sludgeserved as the killers hunting grounds.

Clevelands detective bureau launched a massive effort, putting in hundreds of hours of overtime. When conventional methods failed to bring results, they pushed themselves to devise fresh ones. A veteran detective named Peter Merylo even set himself out as bait, disguised in hobo gear, but the killer remained elusive. Many hoped that the investigation had reached a turning point when Eliot Ness took personal charge in September of 1936, but the scientifically-trained investigator appeared just as flummoxed as the army of detectives under his command.

Ten times in Cleveland a mad headsman has killedand 10 times he has dissected with consummate skill the body of his victim, wrote a