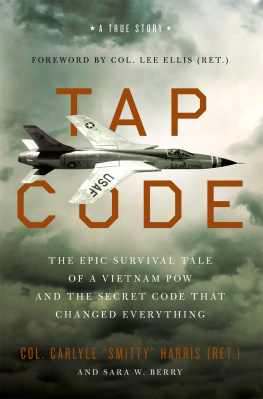

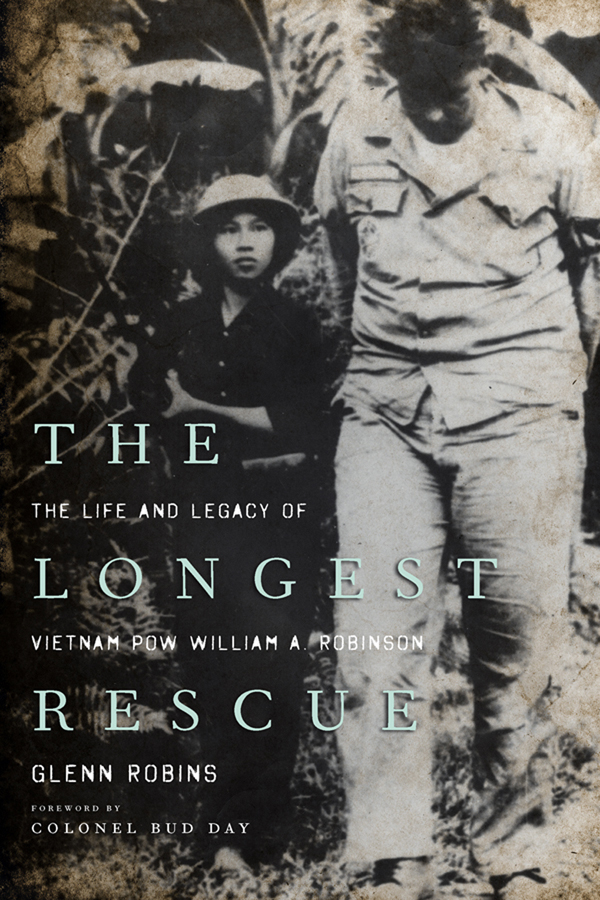

THE LONGEST RESCUE

THE LIFE AND LEGACY OF VIETNAM POW WILLIAM A. ROBINSON

GLENN ROBINS

Foreword by Colonel Bud Day

Copyright 2013 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

17 16 15 14 13 5 4 3 2 1

Maps by Dick Gilbreath, University of Kentucky Cartography Lab

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Robins, Glenn.

The longest rescue : the life and legacy of Vietnam POW William A. Robinson / Glenn Robins ; foreword by Colonel Bud Day.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8131-4323-1 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8131-4325-5 (epub) ISBN 978-0-8131-4324-8 (pdf)

1. Robinson, William A., 1943- 2. Vietnam War, 1961-1975Prisoners and prisons, North Vietnamese. 3. Prisoners of warUnited StatesBiography. 4. Prisoners of warVietnamBiography. 5. Vietnam War, 1961-1975Aerial operations, American. 6. United States. Air Force. Air Rescue ServiceBiography. 7. AirmenUnited StatesBiography. 8. United States. Air ForceNon-commissioned officersBiography. 9. Robinson, William A., 1943- TravelsVietnam. 10. Vietnam War, 1961-1975VeteransBiography. I. Robins, Glenn. II. Title. III. Title: Life and legacy of Vietnam POW William A. Robinson.

DS559.4.R57 2013

959.70437092dc23

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of American University Presses |

Vietnam

Prisoner-of-War Camp Locations

Foreword

This is a very big book about a very big man, with a big mind, and a huge, unshakable stoicism and innate common sense. These were exactly the qualities he called on to resist the brutal and inhumane conditions that he faced as a prisoner of war. As a reader, you will become a better person for having read this spectacular story and following Billy's example. I was shot down over North Vietnam on 26 august 1967. I was shootdown number 138 of those Americans who actually made it into a prison camp. More than that number had already been shot down and murdered by the North Vietnamese. Little did I expect that I would be held a POW for five years and seven months. Billy Robinson, one of the earliest POWs, had already been in captivity for more than two very hard years before my shootdown.

In Hanoi I was held briefly at the Hanoi Hilton, in the old French jail, and then the communists moved me to the Plantation (a few miles southwest of downtown Hanoi), where my multiple broken bones and gunshot wounds began to heal. In December 1967 Lieutenant Commander John S. McCain became my roommate. That was a great break for me. John was all broken up and wounded, but he absolutely refused to die, although at first I expected he would. He was filthy, emaciated, and in a massive cast from his hip to his shoulder, and he stank like a rotten egg. That was of no consequence. I enjoyed more than four months of John McCain's company, until on 30 April 1968, I was abruptly ordered to roll up my blanket and be ready to move. I was on my way to a camp called the Zoo. The political officer at the Plantation advised that I was going to a very hard camp, where [I] would have a chance to think about [my] bad conduct in the Plantation camp. As I would soon learn, the Zoo was a torture camp.

Upon arriving at the Zoo on 1 May, we were immediately put into kneeling torture, a remarkably painful punishment that consisted of kneeling bare-legged on rough concrete, while keeping one's body erect and holding one's arms straight up as if reaching for the stars. This torture was unrelenting, and after a short time I had holes in the skin over my knees and could see the bones in my leg. I wasn't the only onethe damage to my roommate's knees was severe, too. After a few days of this treatment, the brutality eased off, and we began to peek out through a crack in the door, generated by a little push from us and the poor construction work of the enemy. My roommate, Lieutenant Commander Arv Chauncey (shot down 31 May 1967), was lying on the concrete floor and describing to me what could be seen. I replaced him on the floor, pushed the door a little more, and was startled to see a huge POW about thirty feet away from our cell leaving the building next door to us. He was approximately six foot two inches tall and weighed about 210 pounds. He had a very young and unwrinkled face. He was with three other POWs and a young guard who was not much taller than the length of his rifle. I first assumed that he must be Army or Navy, as he was too large to fit in most cockpits or aircraft of that time. He dwarfed the tiny guard. It was an incongruous sight.

Just as I was whispering about what I saw through the crack, our adjoining neighbor Major Jim Kasler (shot down 8 August 1966) tapped through the wall that there were POWs in the yard. I was later moved alone across the camp to the Stable, and I subsequently only caught a glimpse of this huge man. Later roommates described the existence of three enlisted air rescuemen, of whom Billy Robinson was one. Just before I left the Zoo to go to more punishment at New Guy Village, we got a message through the wall that Billy's roommates were putting him and the other enlisted men through an officer training program. I personally endorsed the idea as a very good use of their time and hoped something of value would result from it. The idea of the training was to make them commissioned officers after the senior officer approved the idea, which he did. I did not see Billy again until after our release, when we were invited to the White House for a reception hosted by President Nixon, although we had no time for anything but a hello. The demands on our time were extremely high, but we were all exhilarated by our freedom.

A short time after our release, I received a call from General John Flynn, who had been the senior officer among the POWs in North Vietnam. John had spent his entire time in Hanoi essentially in the same cell with one other senior officer and had been totally out of touch with the comings and goings of the other POWs. John and I and Colonel Dave Winn had been moved together in the Plantation just before our release. I gave John and Dave a summary of the seven years of our collective history, much of which had been related to me by the communications officer from the Zoo, Lieutenant Commander Jack Fellowes. (For POW aficionados, the book