The Mirror

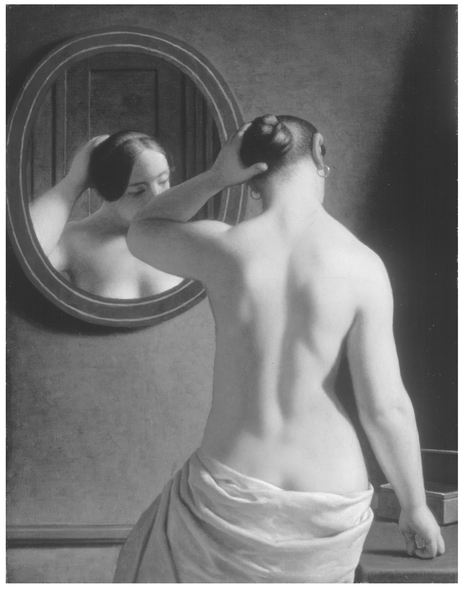

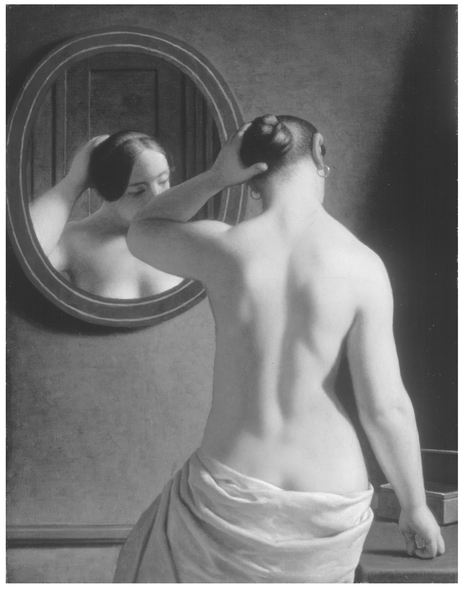

C.W. Eckersberg, Woman before a Mirror (1841). Hirschsprung Collection, Copenhagen, Denmark.

The Mirror

A History

Sabine Melchior-Bonnet

Translated by

Katharine H. Jewett

with a preface by

Jean Delumeau

The Mirror: A History was originally published in French in 1994 under the title Histoire du Miroir

1994 by ditions Imago

Assistance for the translation was provided by the French Ministry of Culture.

First published 2001 by Routledge

Published 2014

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2001 by Routledge

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Melchior-Bonnet, Sabine.

[Histoire du miroir. English]

The mirror: a history / Sabine Melchior-Bonnet; translated by Katherine H. Jewett; with a preface by Jean Delumeau.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-415-92447-2

1.MirrorsHistory. I.Title.

QC385.M4513 2000

155.9'1dc21 00-042204

ISBN-13: 978-1-315-02291-8 (ebk)

Contents

| by Katharine H. Jewett |

| by Jean Delumeau |

In French there are two words that are most often used to denote what we know in English as mirror: glace and miroir ; today they are used almost interchangeably. A miroir is a reflective, generally silvery surface of metal, stone, or glass. In earlier times, however, glace often meant glass, mirrored or not. To indicate the technical difference between glace and miroir in this text, I have translated miroir as mirror and used piece of glass, pane of glass, looking glass, and simply glass to stand for the French glace. When no technical difference is involved, I have used mirror to replace either French term.

The technical detail of Sabine Melchior-Bonnets history of mirror-making posed a challenge with regard to the French word tain , which in English can mean either tin or pewter. In consulting glassmaking manuals that have been translated from French to English, most notably, Alfred Sauzays Wonders of Glass-Making in All Ages (1870), I found that tain is translated as tin and have used that translation here.

Certain loaded terms, such as the French prcieuse , used to describe a seventeenth-century French woman who puts on airs of nobility and learnedness, appear in the original French. The same is true for the titles of the many untranslated texts cited by the author.

Madame Melchior-Bonnet also uses the term italien to refer to inhabitants of Venice in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when there was no Italian nation; the Venetian Republic was its own country. Despite the incorrectness of the term, I have translated her italien as Italian so that the English translation might be as close as possible to the original French.

In the parts of this text that deal with psychoanalysis, my initial attempts to translate the gender neutrality of reflexive French verbs in phrases like le sujet peut se dire (the subject can say to himself or herself ), proved too cumbersome in English. In the end I chose to revert to a masculine subject that represents both genders.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge the indispensable aid of Dr. Kathleen Mulkern Smail in completing this project.

Katharine H. Jewett, Ph.D.

As the reader will quickly become aware, this is a dazzling book. In it, Sabine Melchior-Bonnet marries science and art, literature and philosophy, and history and meditation with a mastery and a quality of writing that is, at times, dizzying. Many of us would like to write as she does, or better yet, to know how to find the brilliant, exact phrasing that enlightens her reader.

The very idea of a historical essay on the mirror is remarkable. How could we not have thought of it earlier? The development of this now ordinary object, once rare and expensive, has marked out the course of our civilization. To guide us in this voyage through time, Sabine Melchior-Bonnet first recalls the primitive techniques of mirror making: the initial use of metal, the slow perfecting of the process of glassmaking, the difficulties of silvering, the passage from blown glass to cast glass, and the major role in the manufacture of mirrors played first by Murano, Italy, then by the Saint-Gobain Company in France.

In the sixteenth century, both steel and glass mirrors were used. But glass triumphed in the seventeenth century, most notably at Versailles, where 306 panes gave the illusion of eighteen huge, solid mirrors. At the end of the century, two-thirds of Parisian households owned a mirror. In the eighteenth century, the object invaded household decor, encroaching on the domain of tapestries. The psych , or free-standing, full-length mirror on a pivoting frame, became popular in the early nineteenth century, a period that later witnessed the success of the mirrored armoire. Today, of course, we see mirrors everywhere without even taking notice of them.

After offering a thorough and precise history of mirror making, Sabine Melchior-Bonnet changes register (without fully departing from the domain of history) in order to examine the changing significance of the mirror in human society, including the many philosophical, psychological, and moral associations that have developed around it over time, like its relationship to good and evil, God and the devil, man and woman, the self and its reflection, the self-portrait and confession. With so many different leads to follow, the author proves a skillful navigator through fascinating terrain, not allowing us to stray offcourse.

I believe I can summarize her intent, rich as it is, by using the two categories of positive and negative, the mirror itself being in essence ambivalent. To whomever knew how to look into it, the mirror once offered an untainted image of divinity. Many painters represented Mary and the baby Jesus holding a mirror. One also said in the Middle Ages that God is the perfect mirror because he is a shining mirror unto himself. Furthermore, Plato affirmed that the soul is the reflection of the divine. Later, Saint Augustine expressed this idea more precisely, in a more tragic mode, suggesting that the man who sees himself in the mirror of the Bible sees both the splendor of God and his own wretchedness. For Drer, who represented himself as the Suffering Christ, man is the self-portrait of God, and Gods face authenticates mans. Yet another aspect of the mirrors meaning was the medieval speculum , such as the one compiled by the thirteenth-century Dominican monk Vincent de Beauvais, a vast encyclopedia attempting to catalog all knowledge. Finally, the numerous metaphorical mirrors of medieval literature, notably the mirrors of princes, constituted a moralistic genre in which readers were invited to look upon an ideal model for their behavior.