The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

1987 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 1987

Printed in the United States of America

Paperback edition 1989

19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 11 12 13 14

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stoller, Paul.

In sorcerys shadow.

1. Songhai (African people) 2. WitchcraftNiger. 3. Ethnology Niger Field work. 4. Stoller, Paul. I. Olkes, Cheryl. II. Title.

DT547.45.S65S76 1987 306'.08996 87-10746

ISBN 0-226-77543-7 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-226-09829-6 (e-book)

The paper used in this publication meet the minimum requiredments of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

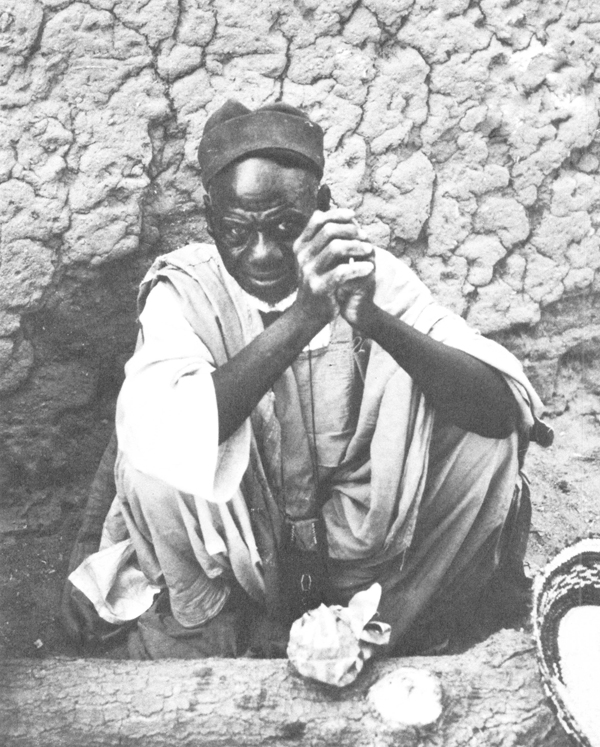

PROLOGUE

From 1976 to 1984 I was the apprentice to Songhay sorcerers living in the villages of Mehanna and Tillaberi in the Republic of Niger. The Songhay, inhabitants of the region since the eighth century, were once the fierce rulers of an extensive, powerful empire; now they are subsistence millet and rice farmers. My apprenticeship, which was spread over five field stays, took me also to Wanzerbe, which is situated in the far northwestern corner of Niger. The inhabitants of Wanzerbe, most of whom are descendants of Sonni Ali Ber, the Magic King of the Songhay Empire (146391), are feared and respected for their feats of sorcery.

As an apprentice I memorized magical incantations, ate the special foods of initiation, and participated indirectly in an attack of sorcery that resulted in the temporary facial paralysis of the sister of the intended victim. As I traveled further into the world of Songhay sorcery, practitioners attacked me, causing on one occasion temporary paralysis in my legs. After that experience in 1979 I learned to eat the powders and wear the objects that would protect me from the will to power of antagonistic sorcerers, and I felt secure enough to return to Niger for subsequent lessons. After Cheryl Olkes and I visited Niger in the summer of 1984, I could no longer pursue my personal quest for comprehension and power; the world in which I had walked was too much with me.

The Representation of Sorcery

My experiences as an apprentice are by no means unique in the community of anthropologists. It is altogether likely that sorcerers have attacked other anthropologists in other societies. And yet, those anthropologists who have observed or experienced something beyond the edge of rationality tend to discuss it almost exclusively in informal settingsover lunch, dinner, or a drink. Serious anthropological discussion of the extraordinary, in fact, transcends the bar or restaurant only on rare occasions (e.g., in Jeanne Favret-Saadas Deadly Words: Witchcraft and Sorcery in the Bocage; or Larry Peters Ecstasy and Healing in Nepal). In formal settings anthropologists are supposed to be dispassionate analysts; because our confrontations with the extraordinary are unscientific, we are not supposed to include them in our discourse. It is simply not appropriate to expose to our colleagues the texture of our hearts or the uncertainties of our gaze.

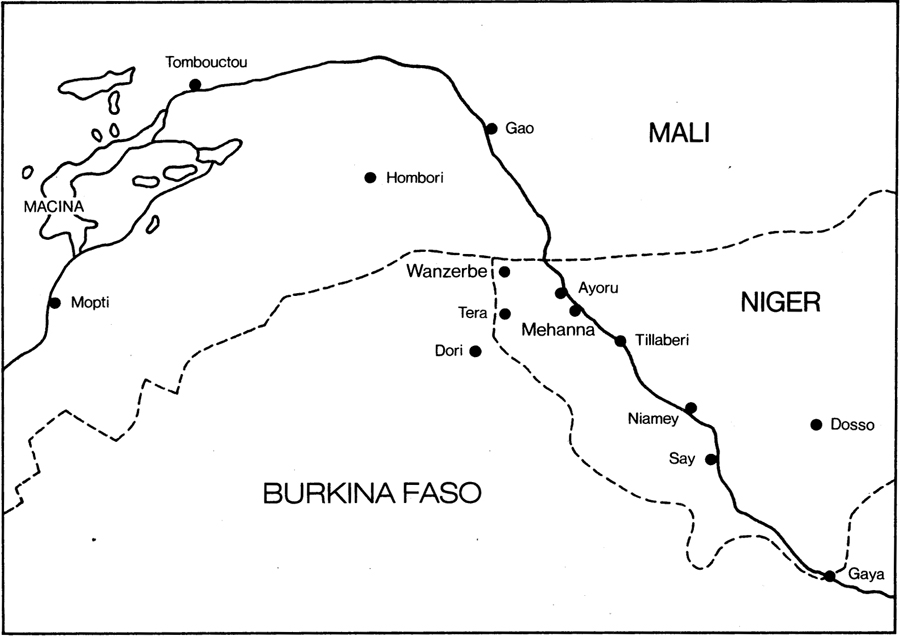

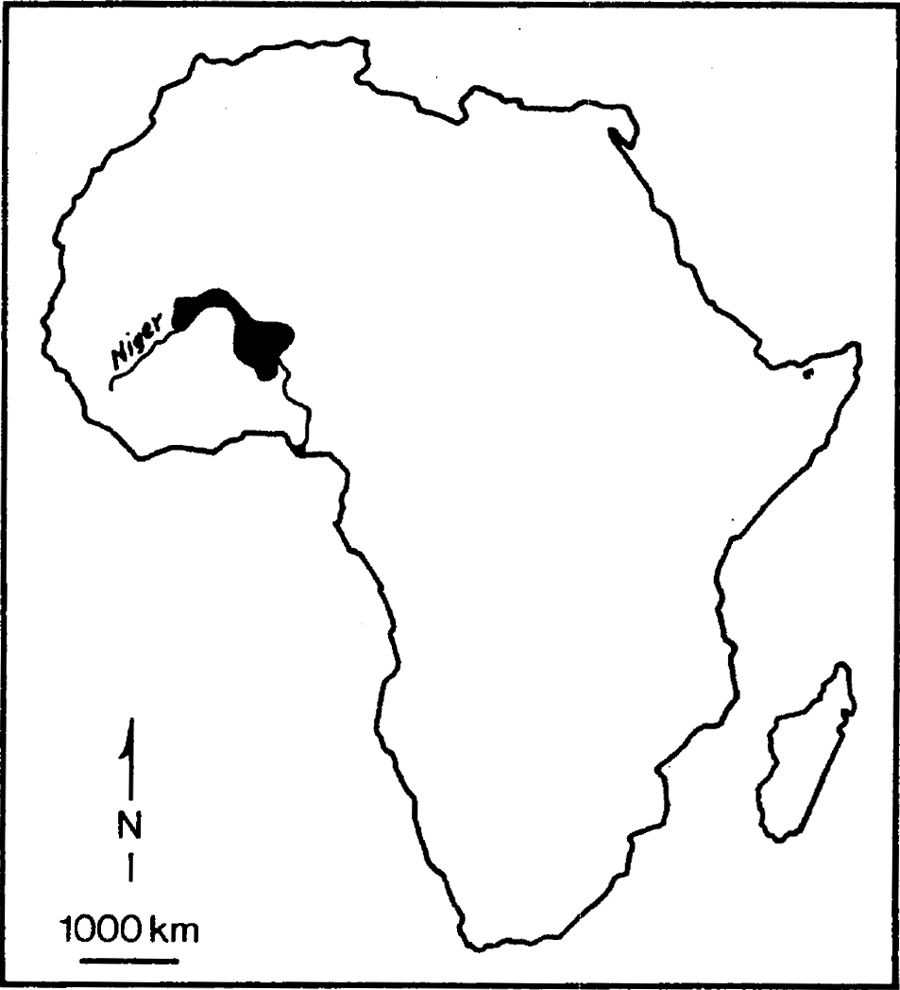

Principal Villages in Songhay Country

Songhay Country

Should I write about being paralyzed in Wanzerbe? Should I describe how a priestess sent spirits to attack me? Is it appropriate to include in ethnographic discourse personal and bizarre accounts? In 1979 my first inclination was to answer these questions with an emphatic No! Indeed, in my first article on Songhay sorcery, I scrupulously avoided mentioning the fact that I had learned much about Songhay sorcery as an initiated apprentice. In that text the only mention of my involvement was relegated to a footnote in which I described how a sorcerer in the village of Mehanna came to accept me as his student-apprentice. Why did I edit myself out of that account? The answer is that we do not usually write what we want to write. In my case I had conformed to one of the conventions of ethnographic realism, according to which the author should be unintrusive in an ethnographic text. There are many other conventions of ethnographic representation to which ethnographers tacitly adhere. Writers like Rabinow, Favret-Saada, Crapanzano, Dumont, and Riesman, among a few others, have tampered with some of these conventions in their works.

In Tales of the Yanomami Jacques Lizot has suggested a relationship between the length of fieldwork and the form of ethnography. Lizot spent six generally uninterrupted years among the Yanomami Indians. The result is an ethnography in the form of stories about life, death, hunting, love, jealousy. These stories involve explicit dialogue and vivid descriptiontechniques that sweep the reader into the Yanomami world.

Like Tales of the Yanomami, this book is the result of a long and intense association with one people, the Songhay in the Republic of Niger. For personal reasons Lizot refused to include himself as a character in his Yanomami stories even though in his books preface he acknowledges his central presence in the ethnographic situations he describes. In this book I am a character in the text; it is an account of my experiences in the Songhay world.

Every ethnographer is a character in the story of his or her fieldwork. In some stories, the best narrative strategy is to distance the narrator from the text; in other stories the presence of the narrator is a source of narrative strength. Michel Leiris is present in the text of his monumental Afrique Fantme, a personal journal that is also an ethnography. The same might be said of Favret-Saada and Contreras Corps Pour Corps or Reads High Valley, Agees Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, or even Lvi-Strauss Tristes Tropiques.

In Sorcerys Shadow is a memoir fashioned from the textures and voices of ethnographic situations. This book is not a standard ethnography; it is a memoir. There are no Songhay informants in this storythere are individuals who behave in very particular ways. Woven throughout the text is the theme of confrontationthe clash of two worlds of reckoning. How far can we go in the quest to understand other peoples? Is it ethical for ethnographers to become apprentice sorcerers in their attempt to learn about sorcery? And what are our motives as ethnographers? Are we seekers of knowledge? Self-actualization? Power? In Sorcerys Shadow attempts to explore these questions.

The Nature of the Book

The book follows the chronological sequence of my apprenticeship among Songhay sorcerers and is divided into five parts, describing events in 197677, 197980, 1981, 198283, and 1984. A key feature of the book is dialogue. Longer narratives like those of Adamu Jenitongo were tape-recorded and translated. Other scenes in the book involving dialogue are reconstructed from my fieldnotes. Generally,

The paper used in this publication meet the minimum requiredments of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meet the minimum requiredments of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.