Copyright 1988 by Evelyn Dahl Reed

Illustrations copyright 1988 by Glen Strock

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data:

Reed, Evelyn Dahl, 1906-

Coyote tales from the Indian pueblos.

Bibliography: p.

1. Pueblo IndiansLegends. 2. Coyote (Legendary character)

3. Indians of North AmericaSouthwest.

NewLegends. I. Title.

E99.P9R27 1988 398.2'452974442 86-14544

ISBN: 0-86534-094-3 (pbk.)

ISBN: 9-78161139-973-8 (e-book)

Published by SUNSTONE PRESS

Post Office Box 2321

Santa Fe. NM 87504-2321 / USA

(505) 988-4418 / orders only (800) 243-5644

FAX (505) 988-1025

CONTENTS

THE STORY SOURCES

It is an old academic question whether or not animal stories existed as Indian oral tradition among the Pueblos before Europeans came to the Southwest. Such tales as "The Medicine Man and The Thunder Knives may be in-digenous. Others, like "The Pine Gum Baby, told to Elsie Clews Parsons at Santa Clara by a man with an adoptive mother from Taos, and The Discontented Farmer, told to Charles Lummis in 1891 by gray-haired Felipe, of Isleta, are almost certainly borrowed from the Old World. But all are entertaining in Indian dress, and that is the basis for the stories included here.

In the sequence, ancient and modern tales are intermingled. They could have been separated only at the sacrifice of readability. These tales have been adapted from the literature buried in the nether regions of museums and libraries and from firsthand tellings of men and women in the Pueblos. For the assiduous collecting of many tales, some of which are retold here, we are deeply indebted to Charles Lummis, Father Noel Dumarest, John Gunn, Elsie Parsons, Ruth Benedict, Elizabeth DeHuff, and others.

Sometimes a story may be unknown in one Pueblo and have several popular variants in another. "The Tail Race is told at Jmez of Coyote and Woodchuck. At Santo Domingo, the Quail play the trick of fastening a topknot on Coyotes head. At Isleta, the music teacher is Locust instead of Horned Toad. At Cochiti, it is the Roadrunner Girls with whom Coyote wants to grind meal. A few stories, such as "The Spotted Deer, seem to be universal. There are eight versions in print: Isleta, (Lummis), San Juan (Parsons), San Ildefonso (Espinosa), Cochiti (Benedict), Sia (Stevenson), Laguna (Parsons), Hopi (DeHuff), Apache (Opler), while the variant related here was told to me at Jmez.

Properly told, the Pueblo animal story is strictly anecdotal, with a formal opening and ending as given here. Winter is the time for storytelling. And evening is the favorite hour. Children gather around the fire, and some older person tells stories interminably, or until all the young ones have fallen asleep.

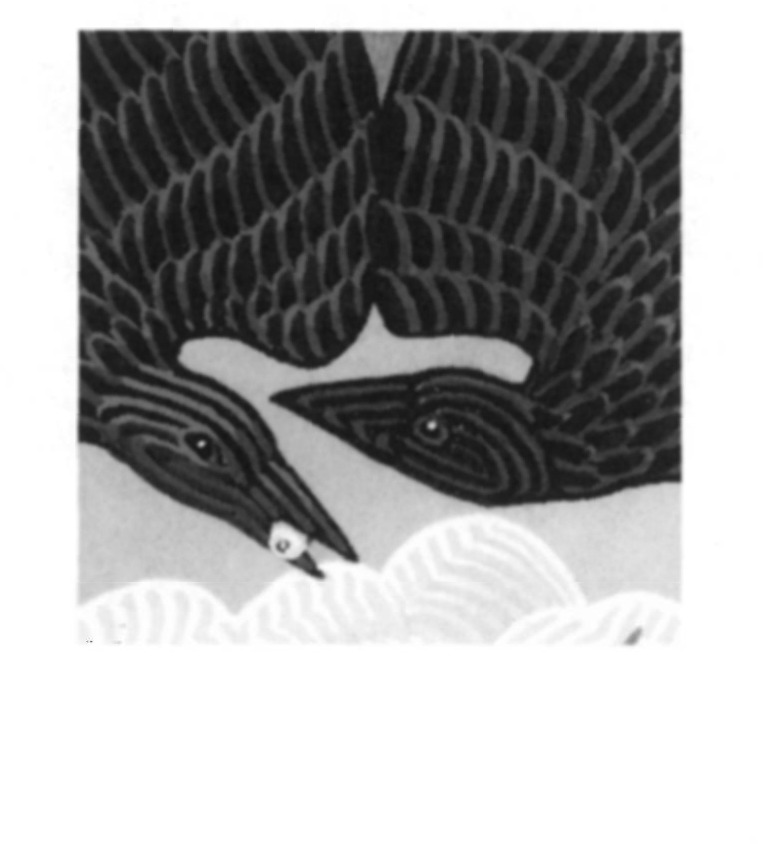

In the animal tales of the Pueblos, Coyote is the scapegoat, the meddling, cowardly, proverbially stupid fellow, not to be confused with Fox, who is very wise. Observe the costume details of the ceremonial dancers, and you will see the fox pelt as an exalted symbol in the religious hierarchy. Only the sacred clowns wear the coyote pelt.

Nevertheless, there is a favorite theme in Pueblo lore that no one is so homely or so dull as not to have some gift for the good of others. Hence, Coyotes misadventures are instructive for the young. These tales, though told for hundreds of years, have a vigor and beauty that only brightens with retelling for children everywhere.

Evelyn Reed

COYOTE THE

ENDURING SYMBOL

One of the most constant symbols of North American Indian mythology is Coyote, a figure that has not only per-sisted but successfully crossed cultural barriers. Coyote survives both as an animal and a myth in literature and art. Contemporary artists such as Harry Fonseca have made a cult of the coyote figure and perpetuated the various legends associated with him.

Coyote is a dichotomous figure. He is perceived as a trickster, a helper, teacher, a fool and a creator. In other words, he is both good and evil. It is said that he possesses every quality of mankind and like humans, he is sometimes a villain, sometimes victim; sometimes a predator, sometimes a savior. And, also like mankind, Coyote is resourceful, tough and enduring.

The trickster is a common character in folktales and Coyote is the best known of the Indian trickster figures. Often depicted as licentious, greedy and a braggart, Coyote is sometimes accompanied by an animal friend. This companion may serve as a foil or an unwitting victim of Coyotes tricks.

Coyote is also a hero figure and creator, a demi-god not unlike the Greek Gods in whom were combined divine attributes and human lust and greed. In some myths, Coyote is the one who got fire and daylight for man and taught him how to be a hunter. Coyote is also thought to have curative powers. According to Crow Indian mythology, the Sun-Coyote created the earth and made living creatures for it.

In some legends, Coyote becomes the one being tricked or the scapegoat. He is frequently bested by those who exploit his greed or turn his cunning against him. However, Coyote can not be destroyed. He has amazing powers of resurrection. Nowhere is this more clearly depicted than in the popular Coyote-Roadrunner cartoons. Althought he is drowned, crushed or falls from great heights Wily E. Coyote comes back to plot another trick.

Why have coyote stories lasted so long? Although they are entertaining one of the purposes of the legends is to point up a moral. Coyote serves as a model of what to do and what not to do. In many of the stories his anti-social behavior results in misfortune. Coyote stories also provide a relief from serious and tense concerns. Listeners or readers are able to take a vicarious delight in Coyotes irreverent attitude toward authority.

Coyote has the power to draw us all, no matter what our ethnic background, into his magic circle. In his own way, he serves to reinforce our human identity.

THE MEDICINE MAN

(Isleta)

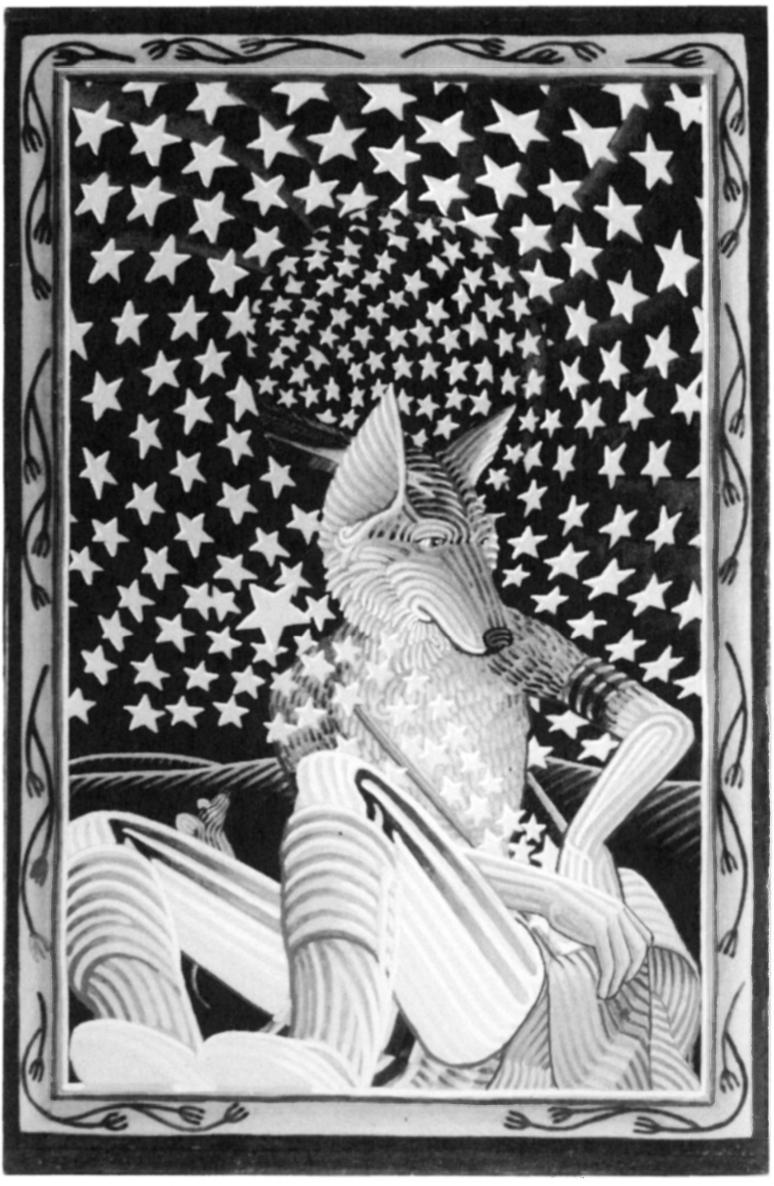

There is a telling that, in the beginning, when the animals first came up from the darkness to live above the ground, Coyote was sent ahead by Thought Woman to carry a buckskin pouch far to the south.

You must be very careful not to open the pouch, she told him, or you will be punished.

For many days, Coyote ran southward with the pouch on his back. But the world was new, and there was nothing to eat along the way, so he grew very hungry. He wondered if there might be food in the pouch. At last, he took it from his back and untied the thongs. He looked inside and saw nothing but stars. Of course, as soon as the pouch was opened, the stars all flew up into the sky, and there they are to this day.