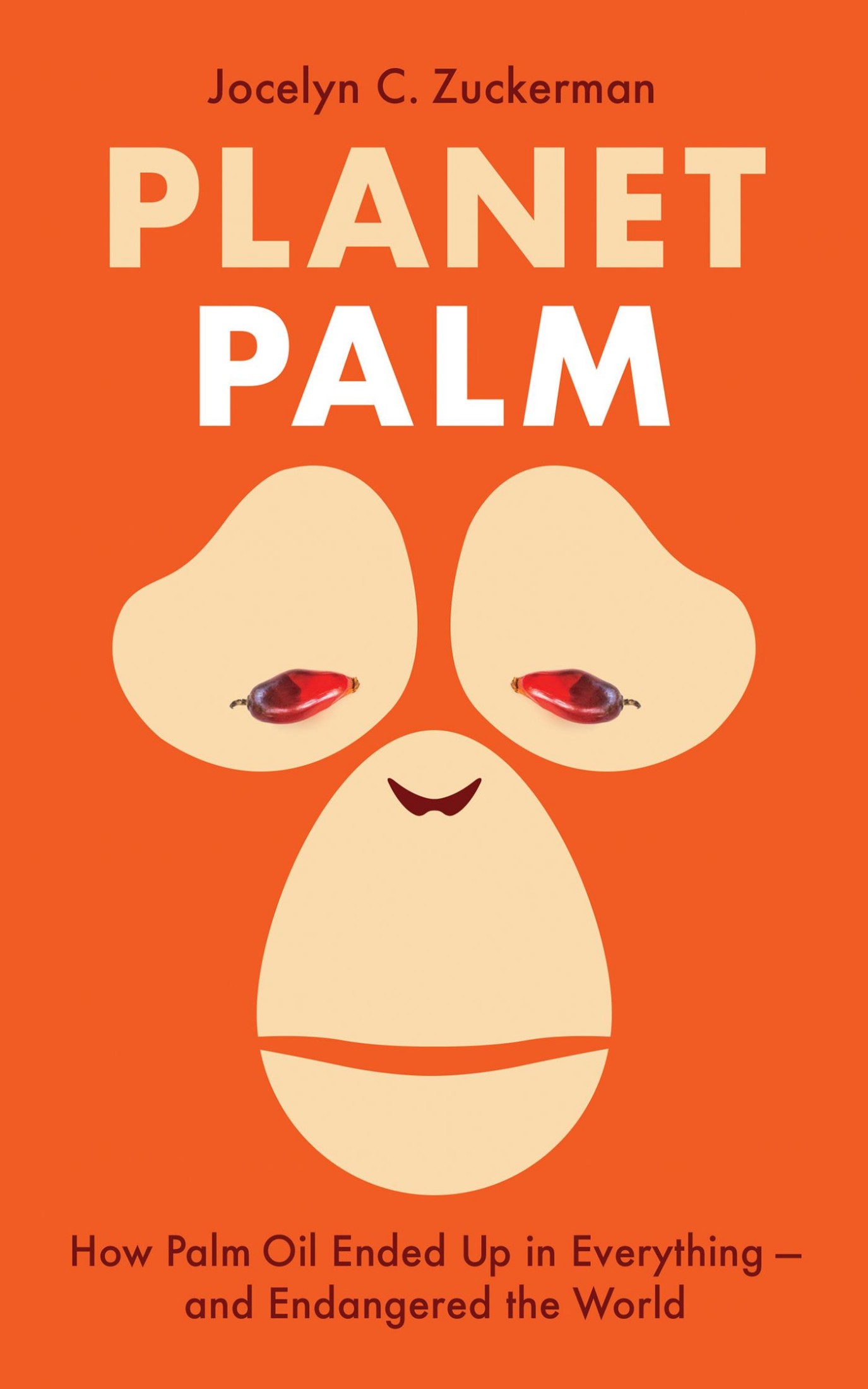

Jocelyn Zuckerman sets out in meticulous, spellbinding detail both the colonial-era historical horrors and the trail of modern-day destruction associated with the palm oil industry worldwide. This book will change not just how you shop, but how you see the world. Mark Lynas, author of Our Final Warning: Six Degrees of Climate Emergency

A carefully researched and gripping book. We cannot tell the story of todays world without that of colonialism, and we cannot tell the story of colonialism without that of palm oilthis is the story of palm oil. Joshua Virasami, author of How to Change It

Zuckerman takes us on a troubling, time-travelling adventure. Today palm oil, [with] its intrinsic links to colonization and slavery, has become ubiquitous in our consumerism culture. Sadly, its nondurable exploitation has had terrible consequences. Not the least among them are global-scale land grabbing and a rapid degradation of our planet. Pierre Thiam, New York City-based chef and cofounder of Yolele Foods

Lively and intriguing Planet Palm will make you look very differently at the items in your kitchen and bathroomand at the persistence of poverty and hunger in parts of the world that should be enjoying plenty. Adam Hochschild, author of King Leopolds Ghost and Bury the Chains

Joceyln Zuckerman has crossed the globe and looked back in time to show us how much the appetite for palm oil profit has cost us in human suffering, environmental degradation and loss of biodiversity. This extraordinary work of investigative journalism will make you cry and gnash your teeth. It will fill you with rage. Essential reading for everyone who wonders if their food choices matter. Ruth Reichl, chef, food writer and restaurant critic

MAN-eating pythons, rogue elephants, organized poachers, armed gangsters, corrupt politicians, murderous executives, modern-day slave owners: Zuckerman encounters all of them in this book, the first exhaustive investigation of the worlds most environmentally damaging productsomething most of us use every day without even knowing it. Barry Estabrook, author of Just Eat and Tomatoland

After reading Planet Palm I now understand that oil palms represent the darkest underside of late-stage capitalism. This is an ugly story, compellingly told. Marion Nestle, Professor of Nutrition, Food Studies and Public Health, Emerita, New York University, and author of Unsavory Truth

PLANET PALM

PLANET PALM

HOW PALM OIL ENDED UP IN EVERYTHINGAND ENDANGERED THE WORLD

JOCELYN C. ZUCKERMAN

Published by arrangement with The New Press, New York

First published in the United Kingdom in 2021 by

C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd.,

83 Torbay Road, London, NW6 7DT

Jocelyn C. Zuckerman, 2021

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United Kingdom

The right of Jocelyn C. Zuckerman to be identified as the author of this publication is asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

A Cataloguing-in-Publication data record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781787383784

This book is printed using paper from registered sustainable and managed sources.

www.hurstpublishers.com

Portions of appeared in different form in Mens Journal.

Book design and composition by Bookbright Media

This book was set in Janson Text

For the keepers of the forests

, the most essential value, because it is the most meaningful, is first and foremost the land: the land, which must provide bread and, naturally, dignity.

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth

CONTENTS

PLANET PALM

PROLOGUE

Oil Crisis

KURT COBAIN was shrieking in my ears. had collected rattan from the forest for building their houses and furniture. The men had returned in the evenings bearing honey, crabs, and groundhogs. Women, their infants tethered to their backs, had bent over plots of yams, melons, and beans in clearings by their huts.

All that remained of such time-honored tableaus now were the thousands of dead trees laid at intervals along the endless expanse of dirt. In the early-morning fog, they evoked fallen soldiers on a still-smoking battlefield. We drove on for miles, past a view comprising only scarred dirt and dead vegetation, punctuated by the occasional bright-yellow CAT excavator. The destruction, in both its scope and its finality, was like nothing Id ever seen. And so had come the pounding drums and sneering guitars of Nirvanas Rape Me, the grim earworm that would become the soundtrack to my trip. The more I saw, the louder the internal rage.

Id driven down to Sinoe County from the Liberian capital, Monrovia, accompanied by an Italian photographer and a couple of local researchers, to report a story about land grabs, or large-scale territorial acquisitions by outsiders. on the staff of Gourmet and written dozens of articles about the environment and agriculture, I knew next to nothing when it came to this substance.

Liberia proved a rude awakening. The violence on display there extended beyond the destruction of the landscape to the Liberians themselves. advocating for the locals lamented the community members loss of identity. The guy who was a respected farmer, he said, has now become a slave laborer.

The company responsible for the changes had been in operation in Sinoe for just thirteen months. an 865,000-acre lease good for sixty-five years, with an option for a thirty-three-year extension. In other words, it was just getting started.

I ended up not going with the Rape Me thing for the start of my articleI could picture my editors rolling their eyesbut the sick-making feeling from that trip stayed with me long after Id filed my piece. The whole experience had hit weirdly close to home. While I may have been clueless about palm oil, I do know something about life on the equator in a remote African village. , I spent two years working as a Peace Corps volunteer in western Kenya. Id taught English and math to high school students in a tiny outpost hundreds of miles from the nearest khaki-clad tourist. There was no electricity or running water in the hamlet known as Buhuyi, and back then there were no cellphones, either. I would wake with the roosters, heat a pan of water over a camp stove for a splash bath, breakfast on papaya and milky tea, and then hop on my bike for the ride down the orange-dirt road to school. In the evenings, Id compose long letters by candlelight or settle in under the mosquito net with a flashlight and a novel. It was lonely at times, and I came down with malaria twice, but in many respects those twenty-seven months were the happiest of my life. I loved the sound of the rain on my corrugated-tin roof, and the smell of the mud drying in the equatorial sun. I loved the slow rhythm of the days, the lack of pretense in my exchanges with the locals, the absence of extraneous anything.

Recently cleared land for oil-palm development in Sinoe County, Liberia.

Of course, there was also deep poverty in that village, and plenty of frustration over the dearth of opportunity and the snail-like pace of change. (Its possible I loved it so much only because I knew I had a ticket out.) But the people of Buhuyi had neat farms and close-knit families. They had rich soil, mango and jackfruit trees, maybe a cow or some chickens. The air was fresh, and the rivers ran clear. We all laughed a lot. In the aftermath of my reporting trip, I was waking from nightmares about having returned to Buhuyi to find that all my students farms had been replanted with oil palm. My village looked like that horrible corner of Liberia.