Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

T HE I NK IN THE G ROOVES

Conversations on Literature and Rock n Roll

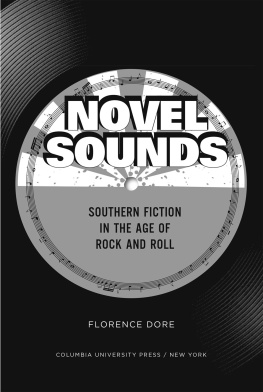

E DITED BY F LORENCE D ORE

C ORNELL U NIVERSITY P RESS

I THACA AND L ONDON

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Ink in the Grooves originated before the COVID-19 pandemic struck and just as I was getting the wheels turning again on my recording career. A world-shattering break, it turns out, will bring some changes. The Ink in the Grooves now includes an essay by John Jeremiah Sullivan, for example, on a song made famous by Canned Heat, and an essay by Dave Grohl about what it was like for him not to be playing live concerts. John Prine was on the list of artists I was hoping to include in the collection. Instead, readers of The Ink in the Grooves will find an interview with members of his band reminiscing about a legend lost.

When the first lockdown edicts were issued in March 2020, I had just finished my first tour in many years and was set to record my new album, Highways and Rocketships. As my band and I were preparing for both tour and studio, the five of us in all of our maskless oblivion crammed into a tiny practice space in Carrboro, Peter Holsapple suggested that we play Marshall Crenshaws Somewhere Down the Line as the cover for our live set. Eager to make my return with louder drums and a telecaster, I opted for Patty Griffins Silver Bells instead. When everything closed down, though, and the world began to feel like a void, I kept hearing Crenshaws gentle lyrics in my head: Somewhere down the line / Its gonna be more than fine / These days will never cross our minds / Somewhere down the line.

So we set up Wills drums in front of the television, a friend left a good vocal mike out on his screened in porch for us to grab, and Peter dropped off a mixer and some mike stands in our driveway. A few bleach-soaked paper towels and some Facetime calls later, there I was, recording Wills drums in front of the television. With Don Dixons production wizardry, as well as Jefferson Holts abiding support and visionwe managed a social-distanced version of recording and kept the musical wheels turning, each band member recording separate parts in his own home, sending tracks to Don via WeTransfer. We were off the road, but we were still moving.

What to do with this track now that violins had been added, vocal tracks had been layered, and all had been mixed? When everything shut down, I had begun scheduling a gig at the legendary Cats Cradle. As the panic and fear of those early days set in, I started worrying that there would not be a Cradle to come back to when all this was behind us. What will happen to the rock venue that make this town what it is, I wondered, and clubs like it all over the country, which fix distant locales in a sprawling rock networkthat web of inconsistent PAs and graffitied rooms into which musicians pour their hearts and souls every night? I ended up joining forces with Steve Balcom, Lane Wurster, and Shawn Nolan, all of whom have deep roots in the Chapel Hill music world, and together we created Cover Charge, a record to benefit Cats Cradle. My bands version of Somewhere Down the Line would be transmitted that way. The dBs immediately offered up an unreleased cover of Im on an Island by the Kinks; I called my former student Libby Rodenbough, and her band Mipso gave us Long-Distance Love by Little Feat. Steve, Lane, and Shawn brought in more and more acts. I wiped down my little red audio interface with a Clorox wipe and placed it in the mailbox for John Wurster, who used it to record drums for Superchunks version of the Go-Gos Cant Stop the World. Cover Charge gained momentum, revered NC bands jumping on right and left to record their covers for the Cradle. Southern Culture on the Skids covered Wilbert Harrisons Lets Work Together for the record, and I asked Sullivan to write something up to help publicize Cover Charge in our local free weekly, the INDYweek. Sullivans piece, as noted, is now gathered in The Ink in the Grooves.

This endeavor, as well as finally finishing Highways and Rocketships once recording in person became safe, made The Ink in the Grooves a different book. I came up with the idea for Ink for old personal reasons, which I discuss in the introductionand because I kept finding myself in conversation both with musicians who considered their craft as related to literature and with novelists indebted to rock. It made sense to bring these musings together. But since the pandemic, The Ink in the Grooves has become more than a conversation. The Ink in the Grooves was amplified by essays, like Sullivans, that came into existence because of the pandemic. But its essence was also touched by the irrepressible musical life force that erupted as the book evolved.

The contributors to The Ink in the Grooves, supreme purveyors of this force, deserve all my gratitude, both for allowing me to bring their moving reflections on the reciprocal links between rock and literature into one place. I owe a debt to them as well for waiting through the months while work on The Ink in the Grooves ground to a halt when musical projects consumed my life. I thank my literary agent David Dunton as well, for jumping on board before this project was fully formed, and Mahinder Kingra, my editor at Cornell University Press, for his superb editorial suggestions. I may have been driving The Ink in the Grooves, but it was Mahinder who kept the motor running. I am grateful for his monumental patience in letting the project sit while first Cover Charge and then recording Highways took priority. And speaking of time, Will and Georgie Rigbyboth so sweet to mefill mine up with love, music, and the kind of support without which nobody could accomplish anything. Will, master of pith and groove, deserves credit for coming up with the title.

Funding for this book came from two generous sources at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill: the Department of English and Comparative Literature and the Institute for the Arts and Humanities. I am deeply grateful to both, as well as to Robert Newman at the National Humanities Center, who hosted the Novel Sounds conferences in 2016 and 2017 that provided a platform for the initial conversations that sparked The Ink in the Grooves.

________________

.

I NTRODUCTION

Needles and Pens

B Y F LORENCE D ORE

Drop the record needle. Drop it on any piece of vinyl in your collection, then go crack open that novel youve been meaning to read. Can you feel the reverberations? Do the lines in the song merge with the sentences on the page? For me, when things settle just right, the world goes away, and I am suspended in a cloud of something bigger than the music or the prose alone. Guitars, sometimes strumming, sometimes screaming; snare snaps; buzzes; the muted pops of ps and ts in the vocals. Sounds blend with other sensations harder to identify: the satisfactions of recurring imagery dawning on the brain, pleasing plot turns, suspense, anticipation of what Vladimir Nabokov described as that golden peace of the story reaching resolution. I was recently visited by a version of this lovely brain fog while staring through the window of my study onto the moss covering the yard, having just immersed in A Gate at the Stairs by Lorrie Moore, the image of a broken gate in my mind, the sound of the knell in Amy Helms voice ringing behind the beat of descending pitch from snare to tom and into the final words of the first verse: Drop the record needle anywhere you please.