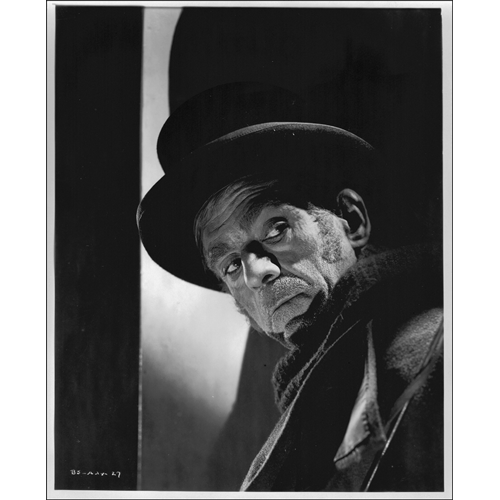

Boris Karloff as John Gray in The Body Snatcher (1945).

for

Donald Craig [Blowzer] Nance

Sing me a song of a lad that is gone,

Say, could that lad be I?

Merry of soul he sailed on a day

Over the sea to Skye.

Preface

Trailing Tusitala

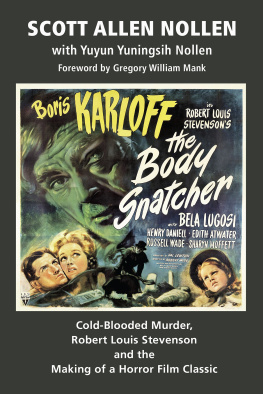

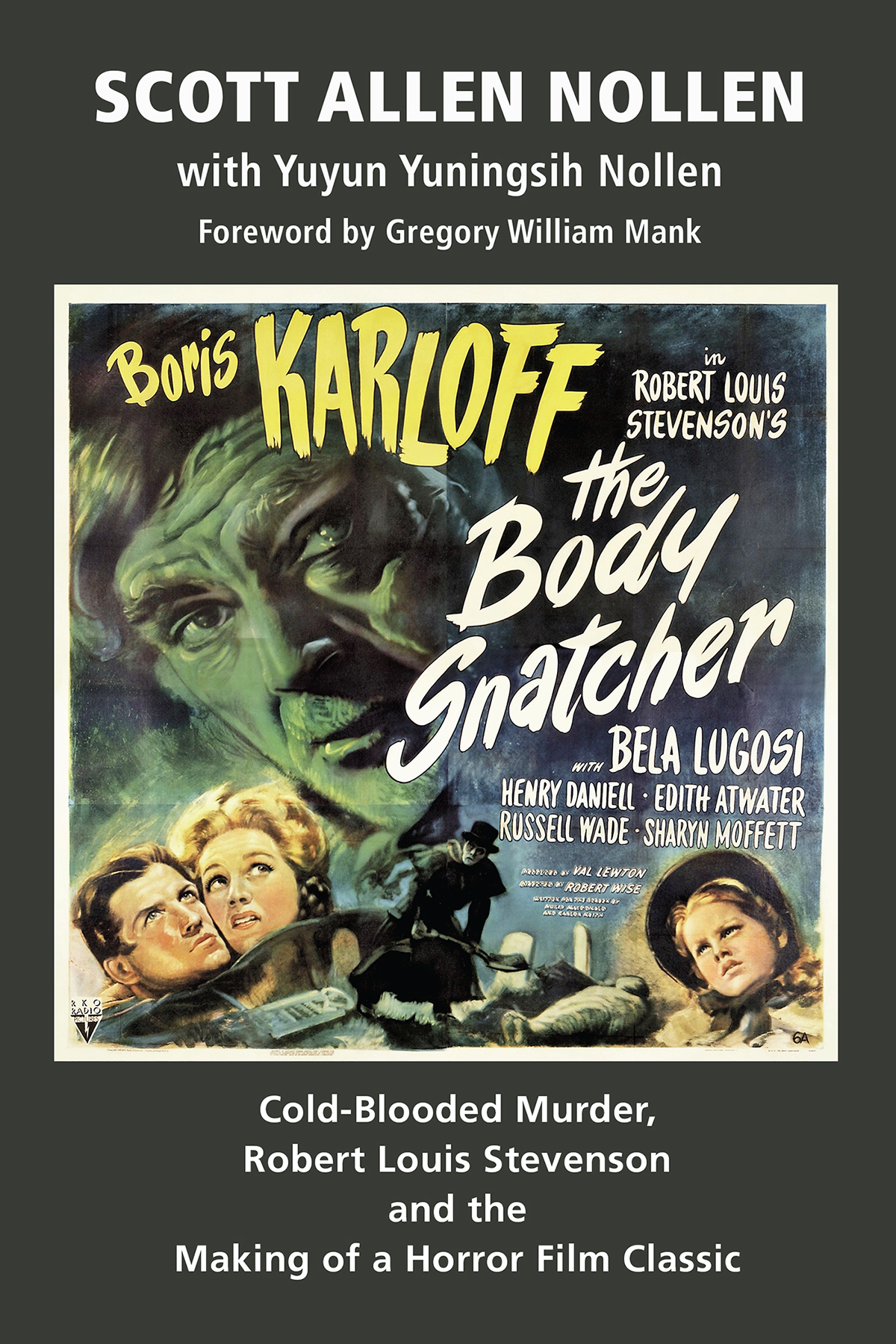

I have seen The Body Snatcher (1945) more often than any other film. After the 100th time, I stopped counting, and that was two decades ago. I also have written about it more than any other film, comprising a chapter in my 1994 book Robert Louis Stevenson: Life, Literature and the Silver Screen and sections of my three volumes on Boris Karloff, published between 1991 and 2021. A few years back, I petitioned the Library of Congress to nominate it for inclusion in the National Film Registry, a valiant but vain attempt.

The first Stevenson story I heard was Treasure Island. While still a bairn, I listened with rapt attention as my father read the novel to me during a succession of bedtime story nights. My initial experience of reading Stevensons work, after discovering a well-worn paperback of collected stories among the family books, occurred at about age nine. Prior to tackling The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, I thought that The Body-Snatcher, a short story, made more sense as an introduction. And, as much as I was intrigued by the more familiar title of the famous novella, the graverobbing designation proved irresistible to a lad who was mesmerized by Boris Karloff films such as Frankenstein and The Mummy, which, on a rare Saturday evening, would air on local commercial television.

In 1972, free from technological distractions, including video (which wouldnt arrive in my domain for six more years), reading was still the alpha and omega of entertainment, and, dare I say, enlightenment. Right and proper, Stevensons story came first, since I was unable to see the film adaptation until after receiving a videocassette copy (containing a very dark, inferior television print) at Yuletide 1980.

Until I met my wife and literary partner in crime, Yuyun Yuningsih Nollen, in 2017, three of the greatest loves of my life were Scotland, Robert Louis Stevenson and Boris Karloff. Combined, they are an all-consuming passion. At the time Robert Louis Stevenson: Life, Literature and the Silver Screen was taking shape, my dream was to, one day, travel to Samoa, where I would visit Tusitalas home, Vailima, and tomb atop Mount Vaea, where he is interred beside his wife, Fanny Osbourne Stevenson.

Though I never made it to Samoa, I ended up more far and away than that, on the South Seas island of Java, in Indonesia. After I became permanently disabled and seriously ill in 2010, I thought my days of being The Vagabond Scholar were over; but little did I know that I would subsequently make a Herculean struggle, traveling more than 100,000 miles between the Western and Eastern hemispheres to get married, therefore prolonging my existence and surviving to write several more books, including this one. Like my literary hero, inspiration and posthumous mentor, I am now in the South Seas, writing with evermore devotion, about Scotland. If it wasnt true, this would read like a Hollywood movie, which brings us to the central subject of this book.

Though I was born in the States, I am indeed a Scott. The research and writing of Robert Louis Stevenson: Life, Literature and the Silver Screen began in 1989, and was greatly inspired by a journey to Scotland in September and October 1990. While enjoying the infinite attractions of Auld Caledonia, I investigated and located many actual sites used by Stevenson in some of his most famous stories, including his superb novel Kidnapped (1886).

To absorb the atmosphere of The Body-Snatcher (written in 1881) on a first-hand basis, I trekked through the Pentland Hills, a picturesque range of braes southwest of Edinburgh, into Midlothian, to explore the kirkyards of Glencorse and Penicuik, where the Fishers Tryst pub was still providing refreshments for the local inhabitants and at least this one visitor. Thats no the stuff they import to the States, Yank, one of them announced.

In those pre-internet days, I benefited from the assistance of the kindly Mrs. P. Ciupik, keeper of a bed-and-breakfast at Polton Bank, Edinburgh, whose German Shepherd, Kate, was more than willing to wolf down the signature Scottish sausages that kept adorning my breakfast plate. Asked about the composition of said sausages, Mrs. Ciupik replied, Well, lad: beef, pork and a wee bit o sheep, tae be sure. Even if it seemed mostly (in Stateside vernacular) mystery meat to me, the high protein served me well during the daylong exploration of the locales used by Stevenson in his story geared to frighten the Very Deil Himsel.

While in Penicuik, some real snatching did occur, when an attendant at a filling station purloined the petrol cap from the rental car after he had topped it off. This necessitated plugging the intake of the tank over the weekend, until a new cap could be purchased the following Monday, at an auto parts store near Glasgow, about 55 miles to the northwest.

During my wanderings, I experienced many other Scottish locales that figure into the story of this book, related not only to Stevensons story but also the historical events that inspired it. Prominent sites in the exploits of Burke and Hare included Greyfriars Kirk and the anatomical laboratory of Dr. Robert Knox.

Several Scottish historians and Stevenson scholars contributed to Life, Literature and the Silver Screen, for which they offered many kind words after its publication. My friend, the late Dr. Ernest Mehew, of Stanmore, Middlesex, was an independent scholar with many connections to British institutions of higher learning, notably the National Library of Scotland. His investigative quest involving a rare original Stevenson letter in my possession at the time (RLS was notorious for leaving his missives undated), in which he was assisted by Robin A. Hill of Edinburgh, resulted in not only an accurate date but also important details that informed that book and, nearly 30 years later, this one.