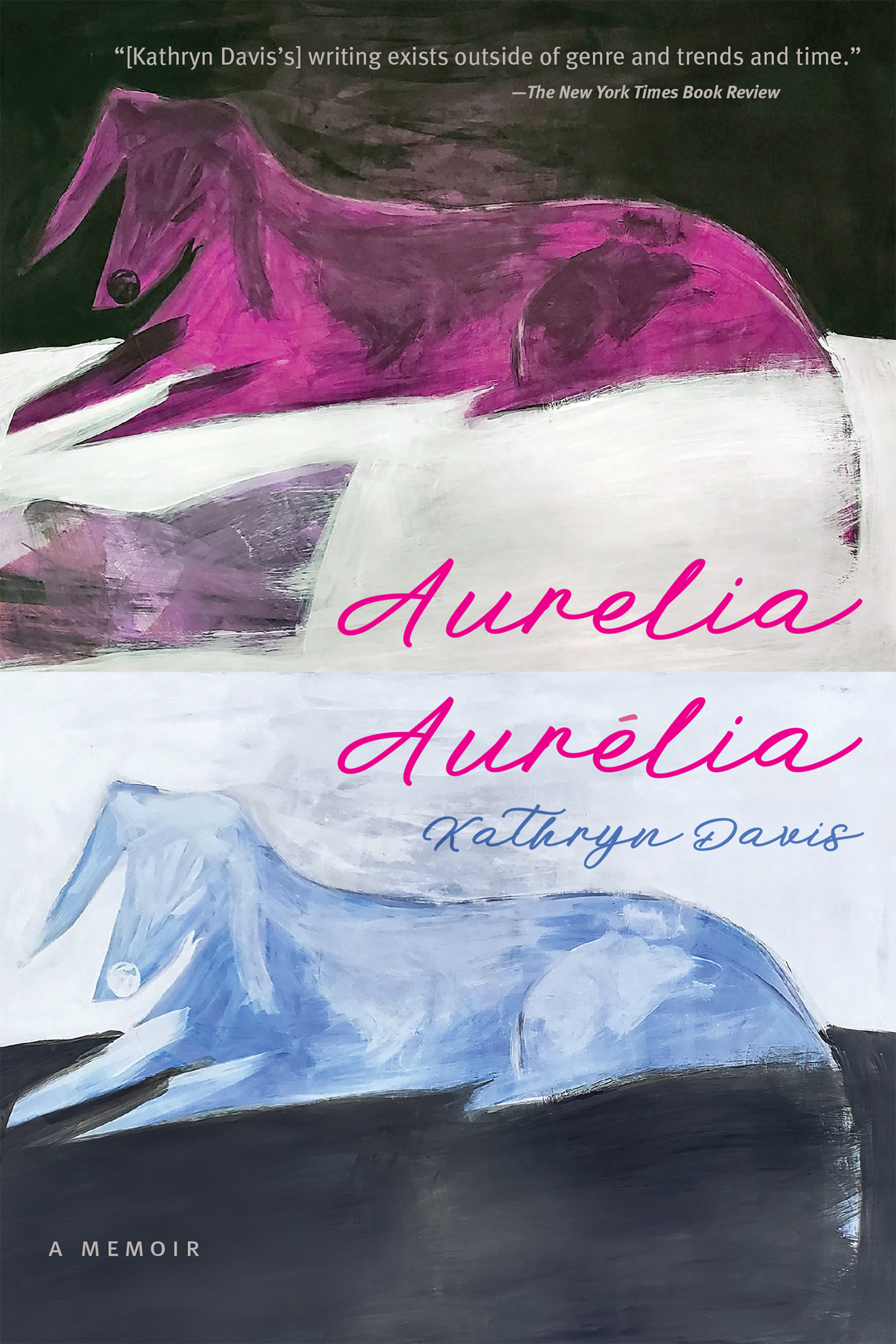

Aurelia, Aurlia

A Memoir

Kathryn Davis

Graywolf Press

Copyright 2022 by Kathryn Davis

Excerpt from The Tibetan Book of the Dead: First Complete Translation edited by Graham Coleman with Thupten Jinpa, translated by Gyurme Dorje, translation copyright 2005 by The Orient Foundation (UK) and Gyurme Dorje. Used by permission of Viking Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

The author and Graywolf Press have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify Graywolf Press at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

This publication is made possible, in part, by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund. Significant support has also been provided by Target Foundation, the McKnight Foundation, the Lannan Foundation, the Amazon Literary Partnership, and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. To these organizations and individuals we offer our heartfelt thanks.

Published by Graywolf Press

250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600

Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401

All rights reserved.

www.graywolfpress.org

Published in the United States of America

ISBN 978-1-64445-078-9

Ebook ISBN 978-1-64445-168-7

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

First Graywolf Printing, 2022

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021940575

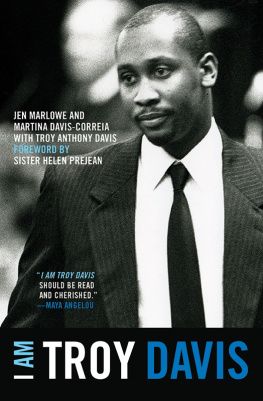

Cover design: Jeenee Lee

Cover art: Anne Davis, Kates Dog

For Louise

There is no other way to understand the procession of dachshunds that follows Kathryns disastrous recital than as a looking glass into Kathryns tempestuous soul. If we were to translate her soul into words, it would say: Look at me! No! Dont look at me! Look at those dogs instead!

Miguel Morales

As everybody knows, one never sees the sun in ones dreams.

Grard de Nerval

Aurelia, Aurlia

Time Passes

There are points in your life when you think youre about to become whatevers next. I was sixteen; I had read the entire Alexandria Quartet and I thought I was an adult. I had read sentences like Watching her thus, trapped for a moment by a rare sunbeam on the dirty window-pane, I could not help reflecting once more that in her there was nothing to control or modify the intuition which she had developed out of a nature gorged upon introspection and had understood nothing except the stupendous effect the language had on me. Empty cadences of sea-water licking its own wounds, sulking along the mouths of the delta, boiling upon those deserted beaches

The first time I inhabited Alexandria it was as a sixteen-year-old high school student living in Philadelphia, the second time, as a twenty-three-year-old married woman living on a Greek island. I was trying to teach myself demotic Greek, using a pocket dictionary and a beautiful two-volume edition of the poetry of C. P. Cavafy. The second time I felt like anything but an adult, a girl in old womans clothing, an impostor, climbing up and down the steep paths of the island every morning with the real old women, all of us dressed in black, all of us looking for kindling. The fallen wood was slick and wet; it was the worst winter anyone could remember. My husbandthe first onewas very sick, the kalva we were renting was cold and damp, and the only thing I could find to start a fire were old Playboy magazines, the paper also slick and wet. I hated my husband. I hated being married. We hated each other, the idea having been that coming to Skiathos would save us from our misery.

You will find no new lands, you will find no other seas So Cavafy wrote of Alexandria in The City. Book in hand I looked back at myself, book in hand. In between came the part of my life called Time Passes.

The first section of To the Lighthouse occupies only a single day, all of it spent delving into the psyche of each of the central characters, rolling them into a great, teeming ball of psyches like the shawl around the skull of the beast in the nursery bedroom. Its governing question is deceptively simple: Will it be possible to make a trip to the lighthouse tomorrow? Mrs. Ramsay says, Yes, of course, if its fine, and her son James is filled with an extraordinary joy until his father shows up. It wont be fine, Mr. Ramsay says, looking out the window. The day could be fine; the day could be not fine. The day could be both things at once.

When I was a girl of sixteen in Philadelphia who thought she was an adult, my first encounter with Virginia Woolf was like that day, fine and not fine. The only thing I knew about her came from the title of Edward Albees play, which some of us had considered putting on until we were told it wouldnt be appropriate. When I asked my English teacher what the title meant, he handed me a copy of To the Lighthouse . Youll like this, he said. Its difficult. She writes about difficult human relationships. Following the bilious confusion of Durrell, Virginia Woolfs languagewhich despite the complexity of her sensibility is remarkably clean and clearentered my soul (to steal her imagery) like a beak.

I didnt need a dictionary to read this book, nor did it drive me to the thesaurus. I didnt need to have experienced true love or sex or marriage or parenthood or old age or deathsubjects I continued to write about, energetically, cluelesslyto make a powerful connection with it. I think this was possible because, despite the books interest in these matters, the dark drumming heart of it, the place I remember best from when I first read it and the place I still return to with quickening breath, is the shortest and weirdest section, the section that announces itself to be, by virtue of its title and everything in it, pure transition.

I was an adult. Id read The Alexandria Quartet . Id gone to Europe on a student ship (the Aurelia the student ship everyone seems to have crossed the Atlantic on in the sixties) where each evening they showed a foreign film in the auditorium. I sat with a group of college students. I wore a paisley scarf, peasant-style and, briefly, feigned a Russian accent. The great mystery of The Seventh Seal was compounded of the film itself (unlike any movie I had seen in my life) and the fact that I couldnt understand what anyone was saying until I read the subtitles. There were Swedish words that thrilled me to the bone. Skat. Riddare. Dden. It was like the word rook in To the Lighthouse . Sound overpowered meaning, as if the word had come into existence first, the thing it defined after.

You could try on personae like dresses. I didnt just want to write like Virginia Woolf; I wanted to be Virginia Woolf. I wanted the brilliant, dogmatic father; the soulful, extroverted mother. I wanted the house on a Hebridean island. I wanted the eyelids. Hearts dearest, why do you cry? the old German professor asked rebellious Jo March, and so I married my first husband because he was German and ten years older than me. There he was, theatrically coughing and gasping for breath on a narrow, damp mattress in a Greek kalva , as meanwhile I fed olive branch after olive branch into the woodstove. My husband was dying of typhoid on the floor of a one-room hospital, the sirocco flinging sand at the window-pane. I was Paul Bowles; I was writing the whole monstrous star-filled sky turning sideways before her eyes.