The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To the Jane Does who came before me, the John Doe who came forward with me, and everyone who helps us remember we have names

This book contains discussions of sexual assault and PTSD. If you or someone you know has been sexually assaulted, please know that theres help, and theres hope.

If you dont know where to start, start with RAINN: rainn.org/resources or (800) 656-4673.

When my bisabuela first came to this country, the most valuable thing she carried with her was something only she could see. The rest was worth almost nothing. The varnished tin of her favorite necklace. The cloth full of the rose hips she seeded and then ate like hard candies. The shoes she wore nearly to dust getting to the house she would be paid to clean, and, eventually, cook in. Even her best dressmoths had eaten constellations of perfectly round holes that mirrored the desert stars they flew beneath.

Years laterwhen there had been a wedding ring, a new stove in a house of her own, a fine dressthe most valuable thing my great-grandmother ever owned was still her way of knowing what bread or sweet would leaven the heart of anyone she met. She could soothe lovesickness with polvorones de naranja, sweet as orange blossoms. She calmed frightened dreams with las nubes, sugared white as far-off stars.

It was a gift my great-grandmother had ever since she was a little girl. And when she died, she passed it to me, even though I was too small to remember her face.

I think of my bisabuela now, just for a second, because the first parking spot I find in the hospital lot is up against a rosebush, the hearty, scrub-like kind she ate rose hips off of.

Then Im back to thinking about the boy slumped in my mothers car.

I dont know his name, or where he lives, or how to get him home, or why he was even at the party tonight. I heard he was visiting from Lancaster, but I also heard Bakersfield, and Ely, Nevada, so at this point he might as well be from the surface of the moon, because no one really knows.

I could check his pockets, but Im counting on the hospital to do that for me.

Besides, nothing good ever came from a brown girl being seen taking a wallet off a white guy.

There was other talk about him at the party. Whispers not just about how hes from the middle of nowhere, but about how hes saving himself for marriage. Too bad for him, Victoria and her friends said. Hes cute, even with the acne.

Victorias compliments always come with qualifiers. She looks good, even with the slutty eyeliner. Or, hes not as ugly as he was last year. Or, the one Ive gotten more than once, shes kind of pretty, even though shes a little fat.

Victoria and her friends declaring this boy cute may be the worst luck hes ever had.

I open the back passenger door. Hes not tall, but hes taller than I am, which makes getting him out of my mothers car and into the doors of the ER even harder. His limbs are slack, like theyre each trying to go a different direction. I have to hold on to him hard enough that my right boob is squished up against him. The curve of my hip shoves up against his leg, jeans fraying against jeans.

I wish I had help with him. I wish I had found Jess before I left the party.

But telling her would have meant having to explain.

The boy from Lancaster or the moon looks so bad that his face, washed-out as printer paper, and his lolling head pull two scrub-uniformed women out from behind the glass window.

They drugged him, I say, as though anyone here will know who they means. We were at a party.

As they take himhe doesnt resist; he isnt conscious enough to resistone of the nurses tells me, The police are going to want to talk to you. Do you want to call your mom or dad?

What? I ask.

I wince at the panic in my voice.

Classic brown-girl error.

My mother says I have to stop acting so jumpy. It makes me look guilty even if I didnt do anything, she says. Its the reason that, in sixth grade, when Jamie Kappe and two girls who were always following her around draped paper towel streamers all over the bathroom, and they pointed at me, the teacher believed them. I was nervous enough to look like I did it.

Theyre just going to ask you some questions, okay? the nurse says, apparently giving me and my panic the benefit of the doubt.

I dont know who he is, I say, blurting it because some part of me thinks itll get me out from under these fluorescents.

But it must sound like a confession, because the nurse gives me a bless-her-heart look.

Youre a good girl, she says. For bringing him in.

This nurse, who looks like one of my cousins but with about half an ounce less eyebrow pencil, thinks Im some kind of buen samaritano. A good-hearted stranger rescuing strange boys from the moral cesspool that is an Astin School party.

But Im not the kind of girl she thinks I am. Im the kind of girl who will make sure Im gone before anyone can ask me anything.

If Im not, Ill have to talk not just about what happened to this boy, but what happened to me. I will have to tell them everything I know about two awful things that happened at the same time, in two different rooms. Me in one, him in the other, the walls so thin I could hear him while I pressed my eyes shut and tried to pretend I was somewhere other than in my own body.

And if someoneespecially this nurse who looks a little like my primaasks me about it, I dont know if Ill be able to stay quiet. And I need to. Because nothing good will ever come from telling the truth about tonight. I already know that. Even under the buzz of the fluorescents and the bucking of my stomach, I know that.

In the morning, this boy and his parents will be informed that there was no sign of penetration, to him or by him. The fact of the lipstick on him will hover, unspoken, in the disinfectant-tinged air. He will know what it means. They will all know what it means.

He will elect not to have a rape kit done, partly out of shame, partly because he knows how difficult it will be to prove he didnt want it.

And because he has never heard of a girl forcing a boy.

His brain is not even sure its possible, even as his body feels the violation tingeing his blood.

Right now, I dont know any of this. Latermuch laterI will. And when I do, I will imagine this boy feeling like some specimen in a jar, a rare pinned moth, thinking its his fault the pin went into him in the first place.

Maybe, if I knew all of that now, I wouldnt do what Im about to do next. Maybe I wouldnt make the decision that will ensure this boy wakes up alone. Maybe if I knew that his mother is hours away, crying at the white lines of the highway because the voice on the phone tells her that her son is in a hospital in San Juan Capistrano, but will not tell her why, I would do it differently.

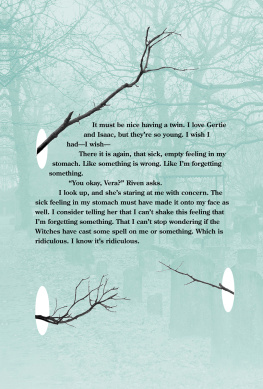

I want to think that. But I know Im wrong. Because even in this moment, as I make this decision, I can guess that when he wakes up, the air will be thick with the vague but heavy sense that something bad has happened to him. But he will not know exactly what or who did it to him or why. A little like the feeling I am already dreading waking up with tomorrow morning, the reverse of that relief you get when you realize a nightmare isnt actually true, that you can let it go now.