About Invisible Publishing

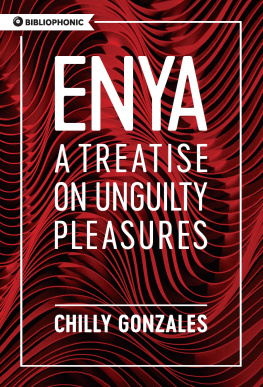

The Bibliophonic Series is a catalogue of the ongoing history of contemporary music. Each book is a time capsule, capturing artists and their work as we see them, providing a unique look at some of todays most exciting musicians.

Invisible Publishing produces fine Canadian literature for those who enjoy such things. As a not-for-profit publisher, our work includes building communities that sustain and encourage engaging, literary, and current writing.

Invisible Publishing has been in operation for over a decade. We released our first fiction titles in the spring of 2007, and our catalogue has come to include works of graphic fiction and non-fiction, pop culture biographies, experimental poetry, and prose.

We are committed to publishing diverse voices and experiences. In acknowledging historical and systemic barriers, and the limits of our existing catalogue, we strongly encourage writers from LGBTQ2SIA+ communities, Indigenous writers, and writers of colour to submit their work.

Invisible Publishing is also home to the Bibliophonic series of music books and the Throwback series of CanLit reissues.

If youd like to know more, please get in touch:

Invisible Publishing

Halifax & Prince Edward County

Copyright Information

Text copyright 2020 Jason Chilly Gonzales Beck

Originally published as Chilly Gonzales ber Enya by Verlag Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any method, without the prior written consent of the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may use brief excerpts in a review, or, in the case of photocopying in Canada, a licence from Access Copyright.

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

Bibliophonic Series editor: Del Cowie

Cover by Megan Fildes

Typeset in Laurentian & Slate by Megan Fildes

With thanks to type designer Rod McDonald

Printed and bound in Canada

Invisible Publishing

Halifax & Prince Edward County

www.invisiblepublishing.com

Published with the generous assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada.

Lullaby Voice

I dont remember my mother ever singing me a lullaby. She had many voices, just not one for lullabies. She had a squawking Jewish mother voice for storytelling, an icy almost-British accent for when she was having fights, an exaggerated Miss Piggy yell to get our attention in the basement (this was the voice she was best known for among my friends) but she didnt have a soothing voice in her repertoire. She was never natural, always performing. So, no lullabies for me.

And anyway, a lullaby isnt a performance. Its basically folk music; it serves a social purpose. The lullaby already existed before the conscious pretense of artistic musical expression. Maybe Im romanticizing, but folk music (communal storytelling through music) always seemed less selfish as compared to pop music (Lionel Richie dancing upside down). At least, my pop music felt selfish: I started making music to get attention, to live out a fantasy. I made sure that my virtuosity was proof of my talent and the worst insult I could imagine was someone telling me it reminded them of a lullaby. My motivation was so ego-driven, how was my music supposed to bind people together? I always envied musicians who made music for a social purpose: gospel musicians for God, DJs for dancing, folk musicians for community, and lullabies for soothing children.

Contra pop music, a lullaby has no backing band or beat. Usually zero accompaniment. It has to work by itself a cappella. You cant rely on a strange, unexpected harmonic twist to provide drama in the musical storytelling, like the nothing really matters chord in the opening of Bohemian Rhapsody. You cant count on a sonic surprise like the awkward stutter of muted guitar strings before the chorus of Radioheads Creep. No saxophone solos, no filter sweep, no autotune. A lullaby, in fact, is pure melody, the voice itself.

Ive always been old-fashioned when it comes to respecting melody. Melody is the surface of a song, the facade of the building. So, when someone asks you if youve heard a new song, theyll just sing the melody. You know the one that goes groove is in the hea-ar-ar-ar-art? For most people, the melody is the whole song.

Harmonythe chords that support the melodyis the invisible foundation of the building. These chords have the unglamorous power to maximize emotions in a song, but chords arent enough to be a song by themselves, and you definitely cant hum a chord. Imagine With or Without You if Bono never started singing. Harmony is melodys bitch, with no life of its own.

Hearing a melody a cappella, divorced from its harmony and expelled from its sound-world, is a kind of test. Does it still sound like music, when its sung, just like that, by a civilian (an amateur)? The ultimate test: How does it sound when sung by your mother?

If it passes this test, the melody indeed becomes the whole songmusics synecdoche. All lullabies have passed this test; theyve survived for centuries. Theyre still there after capitalism, sleeping pills, and the invention of recording, never outgrowing their original purpose.

Thats probably why we dont listen to recordings of lullabies. They dont exist as recordings the way pop songs do. A pop song is a specific moment in time captured by a specific artist; it belongs to that artist and we acknowledge their ownership, it will always sound the same. Hearing it live, or hearing a cover version of it, will still always refer us back to the original.

There is only one Take On Me and it is by a-ha, and if we hear some eighties tribute band performing it, we are comparing it to the 1981 studio performance of Take On Me. There is no imagining the song without the precise combination of cheesy drum sounds and the voice of Morten Harket (I just Googled his name). A pop song is alive only at the moment that it is bornfrom then on it is frozen like a caveman in ice. Its near-impossible to get people to hear a cover of an iconic pop song with fresh ears, as if for the first time. I know; Ive tried.

When I first switched to piano-only concerts in 2004, one of my best/worst ideas was to re-arrange eighties pop songs using jazz and classical gestures. One of the songs I devised was a faux-Baroque arrangement of Enyas Orinoco Flow (the sail away song). But my cover didnt really have a chance to be heard objectively. It could only remind people of the original version, still living rent-free in everyones collective nostalgia-mind.

Folk music doesnt have this baggage: theres no original recording of a lullaby. Its not even something we can evaluate on the basis of musical taste. It either works at its function or it fails. The baby sleeps or it doesnt (as in comedy, the crowd laughs or it doesnt). We dont know or care who composed it. It only matters who is singing it.

So, what kind of voice works when it comes to the lullaby? A soothing voice, a reassuring voice, something that takes away pain, doubt, something that makes the listener feel safe, something gentle and patienta voice you can trust as natural. An unnatural voice may fool some of the people, but authenticity is something that we just know when we hear it.

Some years ago, a friend got so excited to play me something new he had discovered. He couldnt believe I hadnt heard it yet, everyone was talking about it, I was going to love it so much, he said. I hate being told Ill love something before Ive had the chance to decide for myself. He pressed play. Guitar music, not my cup of tea. But it had enough harmonic flair, the feel of the drums was a relatively disciplined combination of modern sounds with just enough surprising moments to give it humanity, there were sonic references I recognized and some I even appreciated and then the singer came in. This singer thought he could fool me by hiding inside this respectable backing track. But his insecurity was audible to me, he was faking it. He had figured out a way to imitate the sound of letting go without letting go. An unmusical persons idea of unrestrained artistry. Barf.