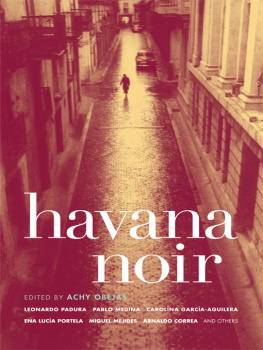

This collection is comprised of works of fiction. All names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the authors imaginations. Any resemblance to real events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Published by Akashic Books

2007 Akashic Books

Series concept by Tim McLoughlin and Johnny Temple

Havana map by Sohrab Habibion

Editorial assistance by Sarah Frank

ePub ISBN-13: 978-1-936070-23-7

ISBN-13: 978-1-933354-38-5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2007926097

All rights reserved

Abik by Yohamna Depestre first appeared, in Spanish, in D-21 (Pinos Nuevos/Letras Cubanas, Havana, Cuba, 2004); Nowhere Man by Miguel Mejides first appeared, in Spanish, in Las Ciudades Imperiales (Editorial Letras Cubanas, Havana, 2006); The Last Passenger by Ena Luca Portela first appeared, in Spanish, in Crtica, No. 119, JanuaryFebruary 2007, the cultural magazine of the Universidad Autnoma in Puebla, Mexico; Staring at the Sun by Leonardo Padura first appeared, in Spanish, in La Puerta de Alcal y Otras Caceras (Ediciones Callejn, Olalla, Spain, 1997).

Akashic Books

PO Box 1456

New York, NY 10009

info@akashicbooks.com

www.akashicbooks.com

ALSO IN THE AKASHIC NOIR SERIES:

Baltimore Noir, edited by Laura Lippman

Bronx Noir, edited by S.J. Rozan

Brooklyn Noir, edited by Tim McLoughlin

Brooklyn Noir 2: The Classics, edited by Tim McLoughlin

Chicago Noir, edited by Neal Pollack

D.C. Noir, edited by George Pelecanos

Detroit Noir, edited by E.J. Olsen & John C. Hocking

Dublin Noir (Ireland), edited by Ken Bruen

London Noir (England), edited by Cathi Unsworth

Los Angeles Noir, edited by Denise Hamilton

Manhattan Noir, edited by Lawrence Block

Miami Noir, edited by Les Standiford

New Orleans Noir, edited by Julie Smith

San Francisco Noir, edited by Peter Maravelis

Twin Cities Noir, edited by Julie Schaper & Steven Horwitz

Wall Street Noir, edited by Peter Spiegelman

FORTHCOMING:

Brooklyn Noir 3, edited by Tim McLoughlin & Thomas Adcock

D.C. Noir 2: The Classics, edited by George Pelecanos

Delhi Noir (India), edited by Hirsh Sawhney

Istanbul Noir (Turkey), edited by Mustafa Ziyalan & Amy Spangler

Lagos Noir (Nigeria), edited by Chris Abani

Las Vegas Noir, edited by Jarret Keene & Todd James Pierce

Paris Noir (France), edited by Aurlien Masson

Queens Noir, edited by Robert Knightly

Rome Noir (Italy), edited by Chiara Stangalino & Maxim Jakubowski

San Francisco Noir 2: The Classics, edited by Peter Maravelis

Toronto Noir (Canada), edited by Janine Armin & Nathaniel G. Moore

For Eva, for so much patience

Many thanks on this project to Arturo Arango, Hayde Arango, Tania Bruguera, Kalisha Buckhanon, Norberto Codina, Arnaldo Correa, David Driscoll, Esther Figueroa, Ambrosio Fornet, Gisela Gonzlez Lpez, Casey Ishitani, Elise Johnson, Caridad Lpez del Pozo, Bayo Ojikutu, Oscar Luis Rodrguez Ramos, Patrick Reichard, Juan Manuel Salvat, Lawrence Schimel, and the inimitable Yoss.

I am especially grateful to Sarah Frank, whose assistance was invaluable throughout the project, and to Johnny Temple, for the opportunity and the faith.

Yo no quito nada I dont take anything away

yo no pongo nada I dont add a thing

Yo no invento I dont make stuff up

Solo cuento lo que veo I just tell it like it is

EL CURI, SOLO CUENTO LO QUE VEO

A FERAL HEART

T o most outsiders, Havana is a tropical wreckage of sin, sex, and noise, a parallel world familiar but exoticand embargoed enough to serve as a release valve for whatever pulse has been repressed or denied.

Long before the Cuban Revolution in 1959 and the United States economic blockade (in place since 1962), Havana was the destination of choice for foreigners who wanted to indulge in what was otherwise forbidden to them: mojitos and mnages, miscegenation and revolution. A photo taken in Havana has always authenticated its subject as a rebel and renegade.

Havana has frequently existed only as myth: a garden of delights, a vortex of tarantism, but alsoperverselythe capital site of a social experiment in which humans somehow deny the worst of our natures. In this novel narrative, Cuba is mystical: without hatred, ism-free, brave and pure, a stranger to greed and murder.

But Havananot the tourists pleasure dome or the Marxist dream-state, but the Havana where Cubans actually liveis a city of ironic and often agonizing contradiction. Its name means site of the waters in the original indigenous tongue, yet there are no beaches. Its legendary for its defiance, but penury and propaganda have made sycophants of many of its citizens before both local authority and foreign opportunity. Its poverty is crushing, but the ingenuity of its people makes it appear resilient and bountiful.

In the real Havanathe aphotic Havana that never appears in the postcards, tourist guides, or testimonies of either the political left or rightthe concept of sin has been banished by the urgency of need. And need inevitably turns the human heart feral. In this Havana, crime and violence, though officially vanquished by revolutionary decree, are wistfully quotidian and vicious.

In the stories of Havana Noir, current and former residents of the citysome internationally known, like Leonardo Padura, others undiscovered and startling, like Yohamna Depestrerelate tales of ambiguous moralities, misologistic brutality, collective cruelty, and the damage inured by self-preservation at all costs.

The noir, it seems, may be particularly apt for Havana: Descriptive rather than prescriptive, noirs explore the symptoms of an ailing society but rarely suggest remedies. They are frequently contestaire in their unblinking portraits but unnervingly apolitical. Their protagonists are alienated and at risk, caught in ethical quandaries outside of their control, and driven to the very edge.

Perhaps surprisingly, these storiesthough fresh and originalhave precedent in Cuban literature. And I dont just mean Paduras morally conflicted detective fiction of the 90s, nor the recent novels of Daniel Chavarra and Arnaldo Correa (whos included here with Olo).

Crime stories, especially those with detective protagonists, try to find order, to right things; noirs wearily revel in the vacuum of values, give in to conflict not as a puzzle to be solved but as a cul-de-sac. Noirs explore and expose but refuse to solve.

As such, the stories in this volume may have more in common with the nihilistic prose of Carlos Montenegros 1938 novel Hombres Sin Mujer (Men Without Women), Lino Novs Calvos 1942 psych-thriller La Noche de Ramn Yenda (Ramn Yendas Night), or even Virgilio Pieras hellish 1943 poem about national identity, La Isla en Peso (Island Burden)all secured within the canon of mainstream Cuban literaturethan with what might pass as normative crime fiction, or even the usual noir.

Actually, when a master like Alejo Carpentier produces a suspense story like 1956s El Acoso (The Chase), and Eliseo Diego opens his 1946 book of blasters, Divertimentos, with a wicked murder story like Las Hermanas (The Sisters), its clear that noir is so bold a streak in Cuban literature that it barely contrasts enough with the mainstream to be recognized as such. And did Reinaldo Arenas ever write anything in which the protagonistnearly always an alter-egowasnt vehemently alienated and at risk?

In all of

Next page