T he Education of a Radical

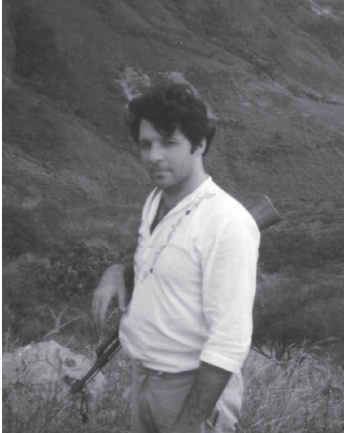

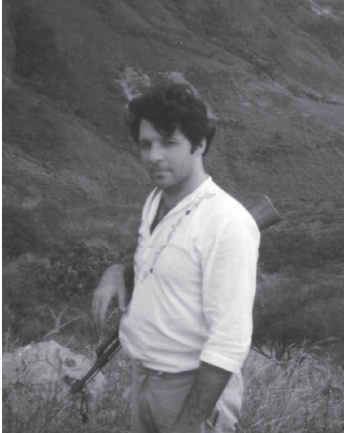

The author in Nicaragua in 1983.

Michael Johns

THE EDUCATION OF A RADICAL

An American Revolutionary in Sandinista Nicaragua

University of Texas Press  Austin

Austin

Copyright 2012 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, 2012

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

www.utexas.edu/utpress/about/bpermission.html

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Johns, Michael

The education of a radical : an American revolutionary in Sandinista Nicaragua / by Michael Johns. 1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-292-73788-4 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-292-74386-1 (paper : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-292-73789-1 (e-book) ISBN 9780292737891 (individual e-book)

1. Johns, Michael, 1958 2. NicaraguaHistory19791990Biography. 3. NicaraguaHistoryRevolution, 1979Participation, American. 4. NicaraguaMilitiaBiography. 5. Frente Sandinista de Liberacin Nacional. 6. Civil warNicaraguaHistory20th century. 7. SocialismNicaraguaHistory20th century. 8. AmericansNicaraguaBiography. 9. RevolutionariesNicaraguaBiography. 10. IntellectualsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

F1528.22.J64A3 2012

972.8505'3dc23 2011041455

For my dear friend Pat and my nephew Josh

CONTENTS

PREFACE

For ten months in 1983 and 1984 I was a would-be revolutionary in Nicaragua. The experience taught me a lesson. As the American writer Bernard DeVoto says, Realism is the most painful, most difficult, and slowest of human faculties.

After leaving Nicaragua with vague but creeping doubts about the Sandinista revolution, it took me several years to see the revolution for what it was. It took me another twenty years to see myself for who I was: to see why I went to Nicaragua and what happened to me while I was there.

Realism came slowly for Sandinistas, too. Sergio Ramrez was one of the revolutions top political leaders and its chief intellectual. In 1991 he wrote an essay for Granta magazine explaining why his Sandinistas had just lost the national elections. After admitting that the Sandinistas plans for collectivized farming seriously undermined all possibilities of winning the allegiance of the peasantswho wanted plots of their ownRamrez blamed the ruinous plans on his noble desire to keep the land from ever falling back into the greediest hands. He conceded that Nicaraguas counterrevolution had become a civil war in the countryside, but he explained it by saying that the peasantrys fears had proved stronger than our promises and thereby split Nicaraguans into those who understood the revolution, and those who could not be reached by it. The revolutions main failing, he seemed to be saying, was its poor sales job. Even after confessing that he and other Sandinista leaders had been arrogant and had lost sight of important elements of political reality, Ramrez buried the revolutions internal problems beneath his dominant story line: the mauling of a heroic little revolution in Central America by the big bad imperialist beast of the north. Less than a year after losing power, Ramrez was still too close to his revolution to see it realistically.

In fact, it took him several years to gain the distance he needed to see the revolution on its own terms and in its full complexity. It took him several years, in other words, to see that the revolutions compassion often took the form of paternalism, that its lofty goals were supported by dubious reasoning, that its good intentions excused bad policies, that its concentration of power jeopardized its democratic ideals, that its absolute faith in the goodness of its aim justified a number of heavy-handed means to bring it about. In the end, Ramrez broke with what remained of the Sandinistas. He called his memoir of the revolution Adis muchachos (So long, boys).

Gioconda Bellis memoir is called The Country under My Skin. Beginning as early as 1984, says the former Sandinista, the Revolution slowly lost its steam, its spark, its positive energy, to be replaced by an unprincipled, manipulative, and populist mentality... we were feeling more and more like spectators to a process that continued to live off its heroic, idealistic image even though, in practice, it was being gutted and turned into an amorphous, arbitrary mess. Belli might have been feeling like a spectator to a wayward revolution, but she did not quite know it: she remained a revolutionary until the Sandinistas were voted out of office.

While Ramrez and Belli tell brave and searching stories from deep inside the revolution, neither tells the story that I want to tell: how the ideal of socialisma political ideal that requires almost complete moral and intellectual certaintybreaks down under the pressure of realism. It is a story, in other words, about how much truth one can see of a socialist revolution and still believe in it.

Im no Voltaire, but as a twenty-four-year-old in Nicaragua I was something like Voltaires Candidein the sense that I too was a young metaphysician entirely unschooled in the ways of the world. And like Candide, I needed many countervailing experiences before finally tempering my enthusiasm for Marxs version of Panglosss theory that every effect has a direct cause in a chain of necessity leading to the best of ends. A grand theory makes life clear and simple. It provides a sense of control and purpose. It gives you an identity. It even charts your course of action. So its very hard to give up.

And the difficulty with describing how I did give it up is that, like Candide, I had only the faintest idea that I was losing my faith. I fought a fierce mental battle in Nicaragua about the Sandinista revolution, but I fought it almost entirely in the back of my mind. So I describe the battle through a series of incidents that, without my quite knowing it, were chipping away at my political certainty while eroding my self-image as an American revolutionary working for socialism in Nicaragua.

Realism does not mean seeing things as they really are. Truth is elusive, especially in politics. Realism means thinking realistically. At its simplest, thinking realistically means allowing yourself to see what George Orwell called uncomfortable factsuncomfortable because they confound your view of the world and your place in it. That is why DeVoto said realism is painful, difficult, and slow. And it is why someone as smart as Charles Darwin had to force himself to follow what he called, in his autobiography, a golden rule, namely, that whenever a published fact, a new observation or thought came across me, which was opposed to my general results, to make a memorandum of it without fail and at once; for I had found by experience that such facts and thoughts were far more apt to escape from the memory than favourable ones.

While in Nicaragua, I had none of Orwells capacity to stare down uncomfortable facts. Nor was I wise or honest enough to follow Darwins rule of writing down everything that ran counter to my ideas. But I did manage to see, if unwittingly, just enough of the Sandinista revolution to get my first lesson in realism.

T he Education of a Radical

On October 25, 1983, I woke up in Managua to the news that the United States was invading Grenada, a tiny Caribbean island whose socialist government was friendly with Cuba, Nicaragua, and the USSR. Like everyone else who heard the news that morning in Nicaragua, I could not help wondering if we were next.

Next page

Austin

Austin