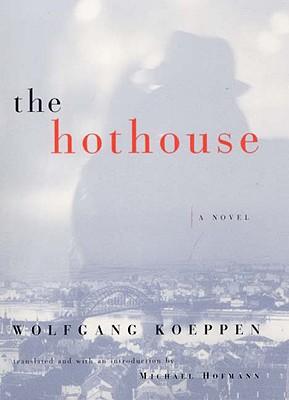

THE

HOTHOUSE

WOLFGANG KOEPPEN

Translated by Michael Hofmann

W. W. Norton & Company New York London

Copyright 1953 Scherz & Goverts Verlag, Stuttgart

Alle Rechte bei und vorbehalten durch Suhrkamp Verlag Frankfurt am Main English translation copyright 2001 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. Introduction copyright by Michael Hofmann Originally published in German as Das Treibhaus by Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main Interior photograph of Bonn courtesy Stadtarchiv Bonn The publication of this work was made possible through a subsidy from Inter Nationes, Bonn, Germany

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Koeppen, Wolfgang, 1906- [Treibhaus. English] The hothouse / Wolfgang Koeppen ; translated and with an introduction by Michael Hofmann. p. cm.

"The Hothouse is the second part of the author's trilogy ... bookended by Tauben im Gras... and Der Tod in Rom"Jkt. ISBN 0-393-04902-7 1. Hofmann, Michael, 1957 Aug. 25

Author's Note [1 9 5 5]

The novel The Hothouse draws on current events, in particular recent political events, but only as a catalyst for the imagination of the author. Personalities, places, and events that occur in the story are nowhere identical with their equivalents in reality. References to living persons are neither made nor intended in what is a purely fictional narrative. The scope of the book lies beyond any connections with individuals, organizations, and events of the present time; which is to say, the novel has its own poetic truthfulness.

God knows politics is a complicated business , and the hearts and minds of men often flutter helplessly around in it, like birds in a net. But if we are unable to feel indignant at a great injustice , we will never be able to act righteously.

H AROLD N ICOLSON

The process of history is combustion.

N OVALIS

Introduction

W OLFGANG K OEPPEN (1906-1996) HAD A VERY long life and a very strange career. Following an obscure, provincial, peripatetic youth on the Baltic coast of Germanynothing to record, no apprenticeships, no achievements, no landmarks, the only thing that characterized him a besetting love of books (asked what the crucial event in his life was, he replied: learning to read; asked another time how he would like to die, he said: in bed, with a book)he had, by the late 1920s, made his way to Berlin (all roads then led, as they do again, to Berlin). There, Koeppen had his only period of regular employment, when he worked on the cultural pages of the BerlinerBrsen-Courier for a couple of years, leaving in 1933, much as Keetenheuve does in The Hothouse, from dislike and apprehension of the Nazis. He left Germany, not for Canada and England, like Keetenheuve, but for Holland. He had, by this time, published a novel, Eine unglckliche Liebe(An Unhappy Love Affair, 1934) with the publisher Cassirer.

It was well reviewed, sold little, and the following year, there was another, DieMauer schwankt (The Tottering Wall), again with Cassirer. Soon thereafter, the newspaper closed down: Cassirer, a Jew, fled, and Koeppen, in Holland with Jewish friends, who were themselves debating where to go and what to do with themselves, decided to return, in late 1938, to Germany, rather than wait to be apprehended. Koeppen lacked the fame, the contacts, on a banal level, the aptitude for languages, and perhaps ultimately, the brute necessity required to make a go of things in exile.

In 1939, extraordinarily, he was on a plane to Berlin. He said: "It is perhaps my only boast not to have served in Hitler's armies for a single hour." What Koeppen did wasPenelope liketo work on unrealized film projects in the Berlin film industry. In 1944, fearing exposure from Nazi colleagues, he made use of the circumstance that his apartment building was destroyed in an Allied air raid, to go underground. He made his way to Munich, where he stuck for fifty years. Munich was the subject and the setting for the first of his second clutch of novels, the so-called "Trilogy" or "Postwar Trilogy" Pigeons on the Grasswhich I describe elsewhere as "set in Munich in a single day, a modernist jigsaw in 110 pieces and showing 30 figures"was published in 1951, closely followed by The Hothouse (1953) and Death in Rome (1954). Then and later (and, for that matter, earlier: Hermann Hesse had praised his second book for a Swedish newspaper), Koeppen was not short of influential supporters among fellow writers, critics, and publishers. Gnter Grass referred to him in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech; Max Frisch and Hans Magnus Enzensberger have praised him in superlatives; Germany's most powerful literary critic, Marcel Reich-Ranicki, has filled a short book with his encomia on Koeppen; Siegfried Unseld, the head of Suhrkamp, first acquired, then promoted and kept faith with and bankrolled his author for over thirty years. And yet, in spite of that, both within Germany and internationally, Koeppen has remained a marginal figure, one for the few, a writers' writer. Why is this?

In the first place, the idea of a literary career assumes a more or less even and continuous output, under more or less stable external conditions. And Koeppen's novelshe wrote no others in his remaining forty years, but more of that later were written and published quickly, spasmodically, over very few years, but in two widely spaced periods. What good to him were his early books, published by a Jewish publisher in the Third Reichboth things that (it was part of his point) the good folks of the fifties were at pains to forget? Karl Korn, the outstanding critic who reviewed both Pigeons on the Grass and The Hothouse in the FrankfurterAllgemeine Zeitung, began by remarking unhappily that Koeppen's name was unknown to all but a couple of dozen people. Looked at in one way, he was a debutant; and in another, he was an experienced writer in mid-career, albeit ending a sixteen-year silence! No wonder people didn't know what to make of him!

And then there was the nature of the books themselves. Reich-Ranicki dubbed The Hothouse "a provocative elegy" and Death in Rome "an alarming provocation"but that was years later. At the time, critics and readers merely felt themselves goaded beyond endurance. The reaction to Koeppen's poetically charged, scathing, rhythmic prose on the part of the morbidly sensitive, anxious, and protective media of the new Federal Republic can only be compared to that of some Soviet bloc country to certain works of samizdat literature with the difference that the work of the censors blue pencil and the secret police was carried out by scribblers in the newspapers and an indifferent public. One review, in a leading German Sunday paper, was headed: "Not to be touched with a barge-pole," another ended: "The public will say 'Crucify him!' He won't care." Another, more "thinky" piece in a monthly magazine was actually followed, many years later, by a "recantation"and how often does that happen in the literary world!? A bookshop in Bonn scheduled a reading from The Hothouse followed by a public discussion with politicians; this was canceled at short notice when the police said they would be unable to guarantee his safety! (They are very different writers, but in his ability to take on his own country, Koeppen reminds me of Tadeusz Konwicki, the great author of The Polish Complex and A Minor Apocalypse.)

The upshot of so much vilification and repression was to repress Koeppen as a novelist. He wrote no more novels. In another one of his characteristic little bursts of activity, he published a series of three travel books on Russia, America, and France, in 1958, 1959, and 1961. The tone taken toward him was transformed: there was, one observer reports, not a single adverse review to any of these! In 1962as a reward for good behavior, the cynic might sayhe was tossed the Bchner Prize. Thereafter, there were many sightings and promisings of further novelsnot least after Koeppen moved to Suhrkampsome of them even fully equipped with titles and settings and plots, but nothing ever appeared. The commodity that Koeppen traded in became silence. Journalists lined up to question Koeppen about his silenceas they did in the United States with the octogenarian Henry Roth, who had been silent for sixty yearsand courteously, helplessly, evasively, he received them. A distressing book of these encounters was published (

Next page