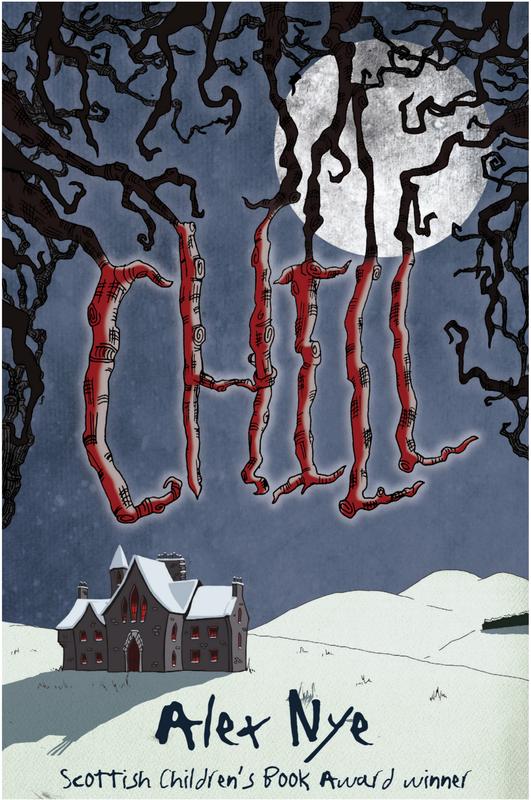

Samuel was alone in the house. Outside the moor lay silent, stretching away into endless emptiness. Dunadd was completely deserted. He liked it this way, having the place entirely to himself. He could almost pretend the house was his. There was an atmosphere of secrecy and silence, which grew more intense when there was no one else about. The others had all gone skiing it was all they could think to do on the snowbound moor. The drifts were so high that the narrow winding road, which led up to the isolated Dunadd House, had become impassable.

It was so quiet. There was nothing but the sound of the wind in the trees, and the distant murmur of the Wharry Burn, water travelling and rumbling beneath ice. The whole moor was covered with snow, an ocean of unending white, waves of it packed up against the walls of the barn and cottage the cottage where Samuel now lived.

The rooms, corridors and staircases of Dunadd House creaked all about him in the silence. Numerous empty rooms lay behind heavy oak doors.

Samuel had felt nervous as he crossed the snowy courtyard, the white tower looming above him, but he was not going to be put off. He made his way up the silent staircase to the drawing room on the first floor.

The grandfather clock ticked noisily in the hall below, a deep sombre note befitting its age, like the heartbeat of the house itself; constant, regular, marking time.

On the wide landing dark wooden doors concealed their secrets from him, but ahead of him one door stood open. He made his way towards it over the polished boards and Turkish carpets. He trod softly, afraid to disturb the peace. The colours of the rugs were beautiful, tawny-red, crimson and tan-coloured, like the flanks and hide of a red deer. The walls were panelled in dark oak, and he was conscious that above and behind him lay another narrower stone staircase, leading into the tower, a place he had never before explored.

He passed shelves of books, old thumbed paperbacks, family favourites, and pushed open the door at the end. Before him lay the drawing room on the first floor, a vast expanse filled with light from the large bay windows on either side. Old pieces of antique furniture stood about in the shadows, gathering dust.

After a week of raging blizzards the moor had at last fallen silent, and sunlight sparkled and reflected from the snow outside, and reached into the dark corners of the house. Dust motes circulated slowly.

Samuel was familiar with this room. He had been here before, most memorably on Christmas Day, just over a week ago, although he preferred not to think about that right now. It only made him nervous, and he didnt want that. He wanted to be able to explore the house, unafraid, without feeling the need to keep glancing back over his shoulder.

He advanced slowly into the centre of the room.

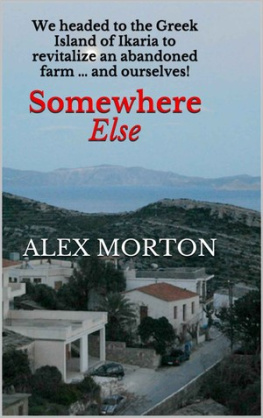

Near the door stood the grand piano, as expected, its lid open and ready to play. Family photographs of the widowed Mrs Morton and her three children stood on its polished surface. At the other end of the room was a massive stone fireplace, its hearth stacked with firewood, unlit at the moment. Mr Hughes would light it later when the family returned. Above the fireplace hung the mirror, framed in elaborate scrolling gilt. Samuel made a deliberate effort not to look into it. He repeatedly drew his eyes away on purpose, especially after what he had last seen there. He didnt want that vision to disturb his dreams again.

He wanted normality, nothing unusual to happen. Or did he? Perhaps he was seeking her out again.

He walked across the drawing room to the window seat on the far side, and sat down with his back to the room. He made himself comfortable and studied the view of the mountains. It was a breathtaking panorama. The whole moor lay beneath him.

He turned his attention to the map underneath the window, a long map of the Highland line, browned with age at the edges, fixed and preserved behind glass. This is what he was here for, ostensibly, to copy the drawing of this map, so that he could have one for his own room. His bedroom in the cottage across the courtyard shared the same view. Mrs Morton had been reluctant to leave him alone in the house at first, but at last she had agreed, and now here he was.

He placed his pens and pencils on a small occasional table and dragged this into position next to him. Then he rolled out his long piece of paper, selected specially for the purpose, and pinned it down onto the table with a weight at either end to stop it from curling inwards.

The oak panelling creaked now and then in the silence, and from a long way away, if he strained his ears, Samuel could still hear the regular, soothing beat of the clock downstairs. He began to draw, his fingers moving rapidly over the paper, his back to the mirror and whatever visions it might contain.

This is an ordinary house, he told himself. Its old and beautiful and very large, but it holds no sinister secrets. He almost believed it for a moment.

There was nothing Samuel loved more than copying maps. He liked drawings with lots of fine lines and detail. It was a gift hed always had. Even as a small child, sitting in front of the television, he had arranged his pens and pencils in neat rows and would draw away with utter contentment for hours.

As he worked he glanced over his shoulder from time to time at the empty room behind him. The mirror over the mantelpiece remained blank, nothing moved or stirred in its silvery depths.

He stopped drawing and listened. He thought hed heard a sound on the staircase. The empty house waited, no sound apart from the distant tick of the grandfather clock and Samuels own breathing. There it was again a light tread on the stair. He decided it was probably Granny Hughes doing her dusting again, despite the fact she had been ordered to rest by Mrs Morton. She often crept about like that, duster in hand, trying to be invisible in spite of her mutterings and groanings.

He turned back to his drawing, his hand poised over the paper, and began to draw a long curving line, more slowly this time, his ear cocked for any sound outside.

Behind him the door swung slowly inwards he could feel the draught of it at his back travelling across the room. Slowly he turned his head, but there was no one there.

Then he heard it.

It was the sound of a woman crying. It filled the room around him, permeating the walls and furniture. A bottled-up sound, trapped, as if echoing along a long dark corridor.

Samuel looked about him, spinning this way and that, but the drawing room was empty. Then he heard her footsteps. She passed through the room to the door of the library at the far end. He couldnt see her, but he could hear her footsteps clearly, and the sound of her weeping. Then the library door closed with a bang, and he was left with a terrible silence.

He dashed across the drawing room, stumbling against the furniture in his haste. When he got to the door of the library he rattled the handle furiously, but it was locked from the inside. He bent down and peered through the keyhole. The key was still in place. He could see nothing.

He stood up and his eye was caught by the mirror over the fireplace. It reflected back no one but himself.

I dont believe in ghosts, he whispered to himself. I dont believe in them. There had to be a logical explanation. Think with the mind, not the heart