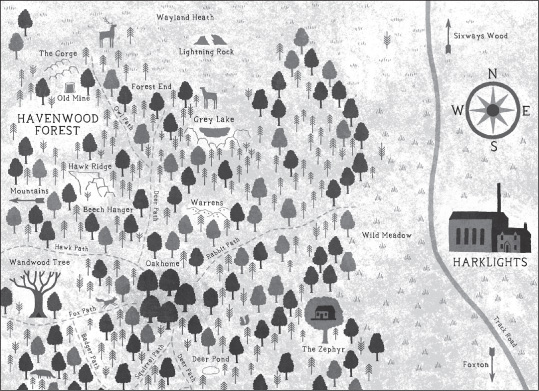

Wick has always lived in the dark and dreadful Harklights Match Factory and Orphanage, working tirelessly for greedy Old Ma Bogey. He only dreams of escaping, until one day a bird drops something impossible and magical at his feet a tiny baby in an acorn cradle

As midnight chimes, Wick is visited by the Hobs, miniature protectors of the forest. Grateful for the kindness shown to their stolen child, they offer Wick the chance of a lifetime escape from Harklights and begin a new life with them in the wild

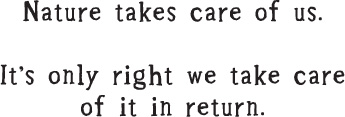

Winner of the Joan Aiken Future Classics Prize, Harklights is a magical story celebrating family, friendship and the natural world, filled with a message of hope for our times.

In memory of my father, your sunshine light lives on.

Old Ma Bogey is coming. We wait, like coiled clock-springs, for announcements. Wait to hear whos getting punishment, or if theres a new orphan. Wingnut jumps out of his seat as Old Ma Bogey marches into the dining room, wearing her usual black fitted jacket and floor-sweeping skirt. Her grey hair is pulled up in a bun at the back of her head. She carries her beating stick. A small boy follows in her wake.

I stop holding my breath and let out a sigh.

Its a new orphan.

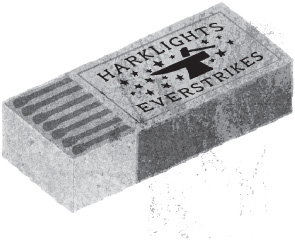

The small boy looks terrified. Hes already dressed in the grey clothes we all wear. A black-and-yellow box of Harklights Everstrikes rattles in his hand. Old Ma Bogey gives every new orphan a box of matches. She says its a gift, the first matchbox packed for you.

Most of us orphans call Miss Boggett Old Ma Bogey behind her back. We call her this because the first thing she does when a new orphan arrives is to take their name away and give them a new one.

Old Ma Bogey wears an iron thumb-guard, which looks like part of a knights gauntlet. She wears it all the time, even though its only to protect her thumb when firing her crossbow.

The matchbox rattles as the boy climbs the steps to the stage.

Old Ma Bogey strikes the stage with the tip of her beating stick and growls, Stand up straight.

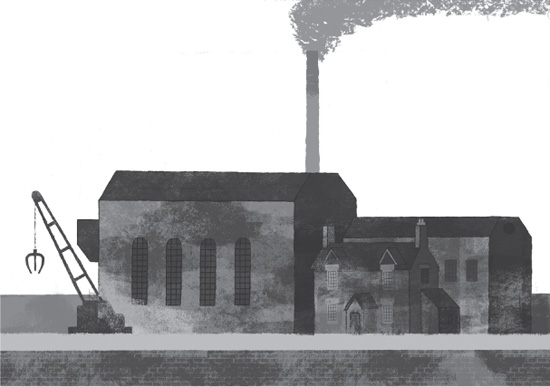

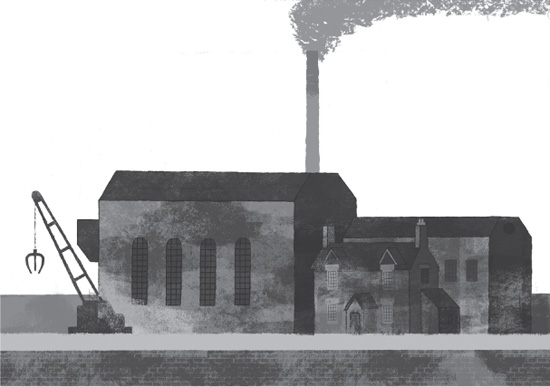

I wonder if the small boy knew his parents. I cant remember mine. Not their faces. Not whether they lived in a town house, shack or anywhere else. My earliest memories are of the factory: prison-high walls, tall iron gates and an enormous chimney, grime-blackened at its tip.

This is Bottletop. He is going to be staying with us. Old Ma Bogey jabs her beating stick at me. Wick, I want you to show him how we do things round here.

My stomach tenses. This could wind up getting me another beating. As I get up from my bench seat at one of the long tables, Petal nudges my elbow. Bet he wont last half a day.

Well see. I hope she isnt right. Otherwise thatll be three orphans in a row gone in a flash and Ill be working next to an empty seat again.

I collect Bottletop. Hes about seven or eight years old, at a guess. His skin is pale as paper it makes him look as if hes been living in a cellar or a coal shed. Hes still rattling the matchbox when I find him a place on the bench next to me.

She took all your things, didnt she? I whisper.

Bottletop nods.

She does that with everybody. Im Wick.

After a few minutes, a door from the kitchen bangs open and Padlock comes through, wheeling a trolley of empty bowls and a brass tea urn. Padlock is the oldest orphan at the factory, and works as Old Ma Bogeys assistant. His stubble is so rough he can strike matches off it. Sometimes he flicks them at us packsmiths. We hate him almost as much as we hate Old Ma Bogey.

He grabs a bowl with one of his thick hands then turns on the brass tap, letting loose a stream of lumpish bone-coloured liquid.

Bottletop gapes at the filled bowl.

Porridge, I say. We get it for every meal. Its not that bad. It doesnt taste of anything, so you can imagine any flavour you like. Make sure you eat it all up or therell be trouble. I nod towards Padlock, whos putting a drop of liquid from a brown bottle in the middle of every bowl of porridge he hands out. And thats medicine. She gives it us so we stay healthy.

Old Ma Bogey and Padlock dont have porridge. At the high table, they eat roast chicken, turkey, duck, sausages and bacon, great joints of beef and lamb, and roast potatoes with thick gravy. For pudding, theres new penny buns, apple pie with custard, sponge cake, plum cake, treacle tart and jam tart, and bread-and-butter pudding. They never share their food, or give us leftovers, even though they leave lots.

After dinner, Old Ma Bogey orders me and Bottletop to come to her office, while Padlock marches the rest of the orphans upstairs. She unlocks the door and ushers us through. Inside, the office is as it always is. Neat and ordered. The desk is empty of paperwork. The only things that sit there are the ink-blotter, oil lamp and the drawer shes taken out from the desk. Its filled with all sorts tools, machine parts, bits of old pocket watches, brass camera lenses and other odds and ends. These are the things she uses to name us.

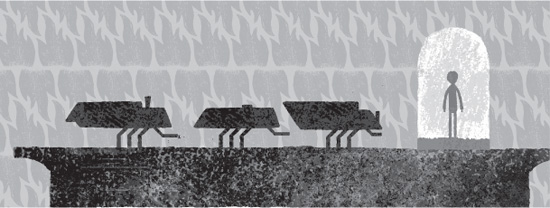

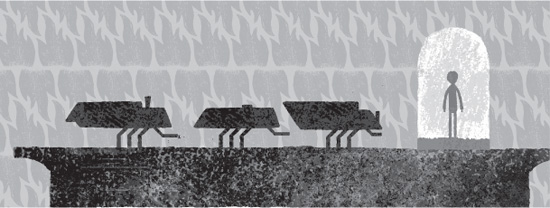

The bell jar is still there on the mantelpiece next to the mechanical beetles Old Ma Bogey likes making. The beetles are impossible things, things that should only exist in story-papers and peoples imaginations. But somehow, she makes them and they chitter and skitter around her office.

Inside the bell jar is a miniature man, no bigger than a couple of matchboxes stood on top of each other, end on end. Hes dressed in dolls clothes and rests on a bed of dried moss and leaves. His skin is thick, leathery, like a glove. His eyes are shut.

Bottletop notices him and has the same reaction as every new orphan disgust and fascination. He shifts on his feet and says nothing as Old Ma Bogey unlocks one of the low cupboards.

Here, this is yours, she barks as she hands him a thin wool blanket, the same ash-grey as her hair, the same ash-grey as our clothes. The only colour anyone sees at Harklights apart from bruises is Old Ma Bogeys blood-red lipstick.

And this, she says, handing him a stick of white chalk. You get a piece once every two weeks and Petal will give you newspaper pictures. A smile curls the corner of her mouth. Use them to remember the things you miss.

Bottletop glances at me, bewildered.

I try and give him a reassuring look.

Scratch, Old Ma Bogeys enormous black cat, skulks into the office and springs up onto the desk. Old Ma Bogey strokes him with her iron-thumbed hand. Shes the only one who can touch him without getting ripped to shreds.

Right, thats it, barks Old Ma Bogey. You can go.

As me and Bottletop climb the main stairs to bed, I stop halfway up by the framed box filled with butterflies. Next to it is a photograph of a man wearing spectacles with grey hexagonal lenses, and an unhappy-looking girl. Hes not real, you know, the little man in the bell jar. Hes made up like that fairy that sells floating soap flakes or the Drink Imp that sells lemonade.

Next page