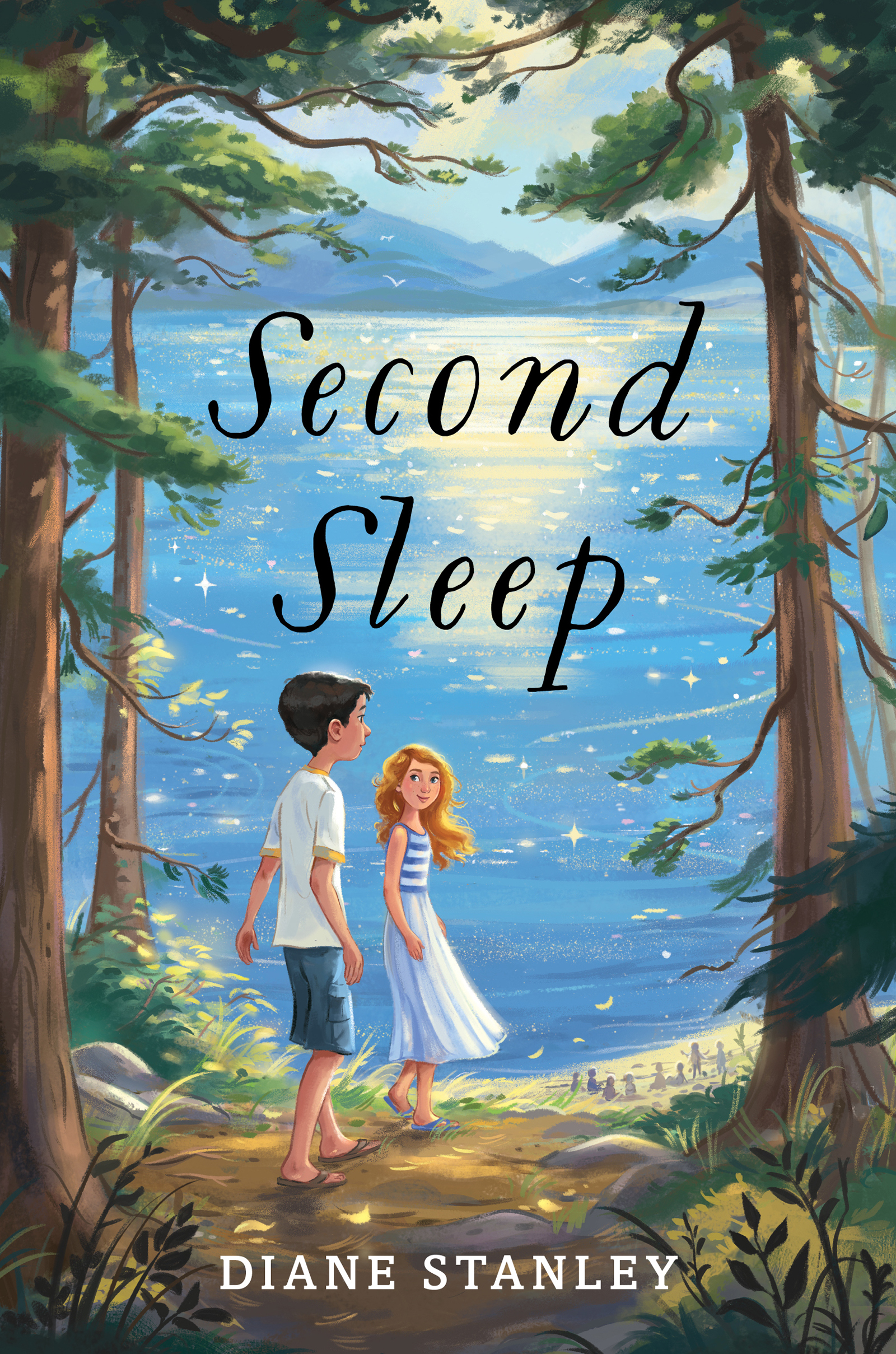

In loving memory of my mother,

Fay Grissom Stanley Shulman,

19201990

For Viola

Contents

IT WAS ONLY AFTER his mom disappeared that Max started playing the game. Hed downloaded it months before because his friend Orson wouldnt shut up about it. The game was simple, he said, something you played on your tablet, but it wasdirect quote heretruly a thing of beauty. Not your typical eye-candy flashy animation that tries to make a fantasy world look real. This game had, according to Orson, elegant graphic design. Which he knew Max would appreciate. And which Max was pretty sure he would once he got around to playing it. But at the time he was still obsessed with Muerte: The Skull.

Then the mom thing happened, and Max got desperate for something to distract him from the dark thoughts that had roosted in his brain like bats in a cave. What he needed was something easy, a game that wouldnt make him think too hard, and wouldnt stress him out any more than he already was. The beautiful and elegant part was just an added bonus.

Turned out, the game met all these requirements. It was, after all, about pruning trees.

So Max opened it and started playing. And right away he saw what Orson meant about the design. It looked like artflat graphics, stark and clean, with hard shapes in red, yellow, and black. The electronic soundtrack was soft and serene, kind of Zen, with just a hint of foreboding.

His task was to help trees grow by carefully pruning them with a swipe of his finger, guiding them, urging them to lean toward the light while protecting them from various kinds of danger. If he failed, he could always grow another one and try again. But if he got it right, the trees would burst into bloom, then the petals would fly off into a star-filled sky with a whooshing sound, like wind.

Everything about the game was gorgeous. Max found himself wishing hed designed it himself. The problem was, it didnt go on in the way it had started. With each new level, the world grew more hostile, with fire and drought, urban sprawl, and the shadows of looming factory buildings, wild winds, and dying soil.

At random times hed get this tiny blue flower, perched on a ledge somewhere, bright and cheerful, a little spark of hope. But that was just a tease because after a while he stopped seeing the flowers anymore. And the trees, no matter what he did to help them, grew gnarled and ugly.

It crept up on him a little at a time. The anxiety began to build and the tasks got harder, until the heart-stopping moment of the muffled explosion, after which the screen went dark. Then the earth was spinning through space and time, the stars whirling by overhead, until it came to rest on the final scene: a single tree, leafless and bent almost to the ground, alone in the darkness of a ruined planet.

But, no, that couldnt be the ending! Max refused to accept it. So he started pruning tenderly, with infinite care, until slowly, slowly it began to right itself, to stand straight, and to grow slowly, slowly toward the light of the stars. Which was all there was leftthe sun was gone.

But the tree never bloomed. Instead, it faded to white, or maybe it was silver, like a ghost tree, terrible and beautiful and unbearably sad.

Max was stunned by that final screen. Because the sense of loss, the hopelessness, was exactly how he was feeling just thenonly without the beautiful graphics and the Zen music.

Yet he didnt delete the game. He started over and played it again, hoping it would be like all the other games hed ever playedthat if he figured out the right tricks and was really smart, eventually he could win. But however many times he played it, the ending was always the same.

So why would he keep playing a game that would always end in tragedy? Because he was addicted to it? Because, no matter how badly things turned out, it was still beautiful? Yes to both.

But it also had something to do with Maxs inner hopefulness. Because deep down he refused to accept anything short of a happy ending. And he was determined to keep trying till he got one. In the game, and in his life.

What Max didnt yet knowthough he would, in timewas that the right trick had never been some secret key or special move. The trick was never giving up.

ITS AN ORDINARY DAY , like any other. In this case a Tuesday in early August. Max and his sister have just come home from Discovery Camp. Which isnt actually a camp, just a summer enrichment program at their school. They like it, though, and go every year.

In the past their downstairs neighbor Penelope would pick them up in the afternoonsfrom school or from campand stay with them till one of their parents got home. But Max has just turned twelve and is now considered old enough to take charge of Rosie on the subway and at home.

He has mixed feelings about this. Rosie can be a real pain. And if she has a meltdown and hes the one in charge, hell have to deal with it. On the other hand, it means a significant increase in his allowance. And its nice to be trusted.

On this particular, ordinary day Max is feeling pretty full of himself. Like hes the third adult in the family now, with all this new authority to swing around. Also, hes pumped about his art class at camp. Theyd worked on etchings that day, which was something new and totally coolscratching images onto a metal plate with a stylus, rubbing ink into the scratches, then wiping off the rest, then putting the plate through a press, where the image is transferred through pressure onto a special kind of soft paper.

He loves the feeling of the stylus in his hand, the little scratches in the metal that will become thin black lines, and the way he has to think backward, because the image will be reversed when its printed. Max feels this technique is perfectly aligned to the way his brain works. His teacher apparently thinks so too. This very day he said Max was a natural.

Their dad comes home at the usual time, around six thirty. He asks how their day went, as he always does, usually in the exact same words. They answer, as they always do, that their day was fine. Then Dad says, like its nothing special, Mom wont be home for dinner tonight.

This doesnt strike Max as unusual. He doesnt ask why she wont be home, whether she has a patient in crisis at the cancer center, or has gone to a conference, or what. He just opens the kitchen drawer where they keep the take-out menus and flips through them. Later, he wont recall what they ordered, or what he did that night. Its too routine to leave a trace in his memory.

It goes on like that for two more days, by which point, for reasons he cant quite put his finger on, Max has started to feel uneasy. He assumes his mom is doing something work-related. And his dad doesnt seem concerned. But somewhere deep in his consciousness he has the sense that something is off.

Her absence has caused a shift in their routines. Theyve retreated to their separate corners, plugged into their devices, hardly talk to each other anymore. Theyre like a table thats missing a leg. It no longer functions. Lean on it and itll tip over. His mom, Max realizes for the first time, is the essential elementthe sun to their planets.

Another day passes. Its Friday. Theyve eaten their latest take-out dinner, pretty much in silence. Now Rosie has plopped herself down in front of the TV, which Dad has chosen to ignore because hes in his bedroom messing with his computer. Max figures that if watching endless hours of TV will keep his sister from whining or acting weird, then hooray. He goes into his room to work on a preparatory drawing for his art class on Monday.