To my daughters, Tilly and Una

Contents

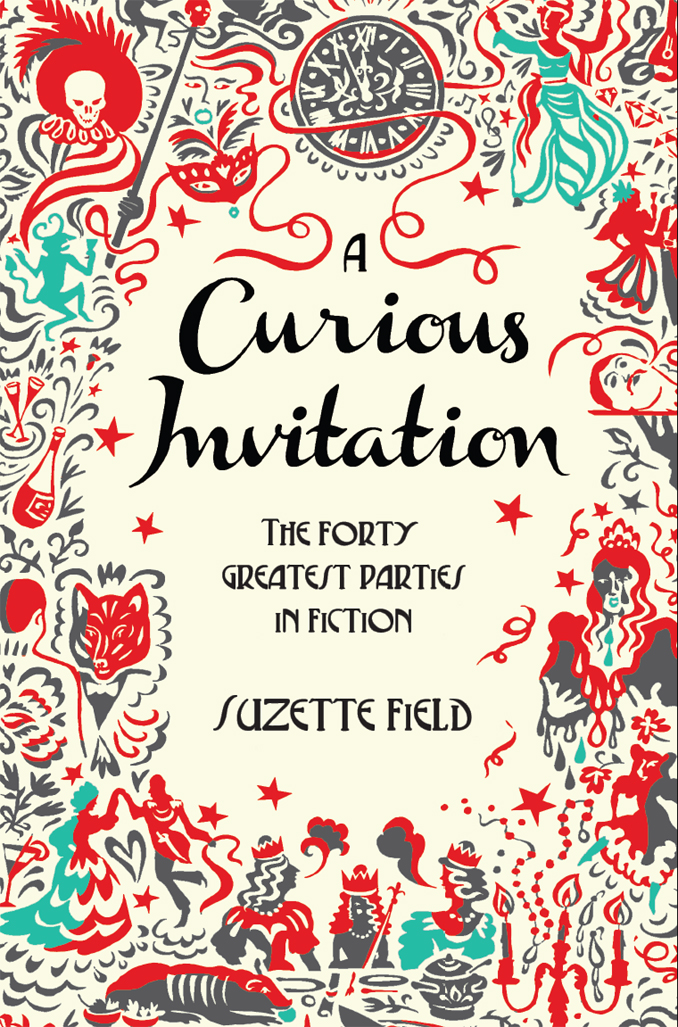

It was Ptah-Hotep, an Egyptian official of the 24th century BC , who first expressed the sentiment All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy and it has been used as an excuse for throwing a party ever since. From ancient times human beings have come together for social purposes. Men and women, hunters and gatherers, shared food and lodgings as a natural consequence of tribal living. All major events in the life of a community and its members births, marriages, deaths, victories, harvests were marked with a ritual or festivity. These would have included eating, drinking, dancing, singing, perhaps the odd virgin sacrifice most of the elements we recognize of a successful party today.

It was only towards the mid-eighteenth century that the word party, meaning a group of people gathered together for a common purpose (e.g. a political party, a hunting party etc.), began to acquire its modern sense of a group of people gathered together for the common purpose of drinking, talking, flirting and networking. As the Industrial Revolution took hold and human beings started to move away from small communities and became increasingly urbanized and isolated in their lives the traditional structures began to change, yet the psychological need for festive gatherings remained. As public festivals declined private parties began to grow in importance.

Unfortunately, there are very few records of these events. The food consumed at parties occasionally survives via menus or tradesmens invoices and guest lists sometimes appeared in the society pages of newspapers, but for the most part we have little knowledge of what these gatherings were like. We can find accounts in the diaries of individuals of the time, but Samuel Pepys, for example, only went to a handful of parties in the whole nine years he kept his journal. Maybe the problem is that the sort of people who would have time to sit down in the evening and write up a diary were those who by definition didnt have much of a social life.

This is where literature comes in. As Aristotle said, art takes nature as its model, and the creative works of an age can offer a valuable insight into what form contemporary celebrations would have taken.

Some of the parties that feature in literature are drawn directly from reality: the Duchess of Richmonds Ball, which appears in works by Byron and Thackeray, was an actual party hosted on the eve of the Battle of Quatre Bras in the Napoleonic War. Agathons dinner party, immortalized in Platos Symposium , really took place with the philosopher Socrates and the playwright Aristophanes on the guest list.

Other literary parties are thinly disguised fictionalizations of occasions which the author attended: Satans Rout in The Master and Margarita is based on a lavish Spring Ball given at the American Embassy in Moscow in 1935 and the Society of Artists Fancy Dress Ball in Steppenwolf was inspired by a Dadaist party in Zurich.

That is not to say that writers dont sometimes just make the whole thing up. Douglas Adams clearly never went to a Flying Party hovering over the surface of an alien planet, and one wonders if the notoriously reclusive Thomas Pynchon ever actually attended an orgy like the one he so graphically describes in Gravitys Rainbow .

In writing about parties authors are doing more than just giving us a glimpse of the mores of their time. A social gathering is a useful dramatic tool, providing a location where characters can interact. A party can be the scene for a meeting, a snub, a seduction, or a murder. It can be an opportunity for social advancement (Roxana, Oskar Matzerath, Alice) or failure (Charles Pooter, Sherman McCoy, Ross Conti). A character can experience triumph (Jim Dixon, Pooh Bear, Rafal de Valentin) or humiliation (Mrs de Winter, Carrie White, Lord Simon Balcairn).

An encounter at a party can be the instant where characters fates are determined: Augustin Meaulnes falls in love with Yvonne de Galais at the Strange Fte, Ivan Ivanovich and Ivan Nikiforovich fall out for ever at the Chief of Polices Reception; or the occasion can supply the backdrop for dramatic events: Dmitri Karamazovs arrest for murder, the destruction of Thomas Ewen High School.

People have always pointed out that there is nothing new under the sun (the expression comes from the Book of Ecclesiastes) and this is never truer than when applied to parties. Dress codes and etiquette may have varied over the ages but social behaviour has remained remarkably consistent. The conversation at Trimalchios dinner party (which is set during the reign of the Emperor Nero) revolves around sport, the cost of living, the weather and how young people have no respect for their elders.

It has been a common complaint over recent decades that our culture is in moral decline, but, as we can see from the above, this belief was equally prevalent in Roman days. Society today is no more decadent (and possibly even less so) than in previous centuries. Alan Hollinghurst writes about gay sex, but so did Plato and Petronius (the latter rather more raunchily). Perhaps decadence goes in waves and we, living in the supposedly permissive society that began in the 1960s, are just starting to get up to speed again after the extreme puritanism of the Victorian age. Or maybe our definition of what constitutes decadence varies. The Satyricon and The Bonfire of the Vanities show the contrasting forms that excess can take. Roman banquets were all about how much you could eat and 1980s Manhattan dinner parties about how little. Both were essentially ways of bragging about how much money you had.

Parties, being occasions where people are at their most ostentatious, provide writers with the perfect vehicle for a spot of social satire: the pretentiousness and vulgarity of nouveau riche hosts (Trimalchio, Mrs Leo Hunter, the Bavardages); the boorishness of guests (the bankers at the Wonderland Banquet, the hobbits at Bilbo Bagginss birthday, the hoolivans at Finnegans Wake); the faux sophistication of food (lobster mayonnaise comes in for a lot of stick) and truly terrible musical entertainment (Dickenss something-ean folk ensemble, Mrs Apes Angels in Vile Bodies , Ric and Phils disco show in Hollywood Wives ).

In addition to these historical and satirical functions parties are a good embodiment of another precept from the Bible: Eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die. For some party hosts and guests the bit about dying can come true rather too literally: Belshazzar, Lord Simon Balcairn, most of the seniors at the prom at Thomas Ewen High and absolutely everyone at the Masque of the Red Death fail to make it through to the hangover stage the next morning.

Merry-making and mortality are routinely linked in literature. Trimalchio stages his own funeral at his dinner party in a mawkish illustration of the biblical maxim. The warriors taking part in Valhallas permanent bacchanalia frequently die, but are handily restored to life the next day to continue feasting. Tim Finnegan manages to come back from the dead during his wake. The guests at Satans Rout are already long dead, but this doesnt seem to diminish their appetite for good living.

Luckily for the purposes of this book, literary heroes and heroines have a lot of spare time to go to parties. This is because very few of them have anything resembling a job. And on the odd occasion when the central protagonist of a book does hold down some form of proper employment it is usually just an excuse for the author to poke fun at them (Mr Hokosawa is a workaholic, Mr Pooter a drudge, Sherman McCoy a Yuppie, etc).

So art, as we have seen, imitates life, but it can also be the other way round. Oscar Wilde stated that the self-conscious aim of Life is to find expression, and that Art offers it certain beautiful forms through which it may realise that energy. Following this principle, literary parties can serve as the inspiration for real life parties.