Table of Contents

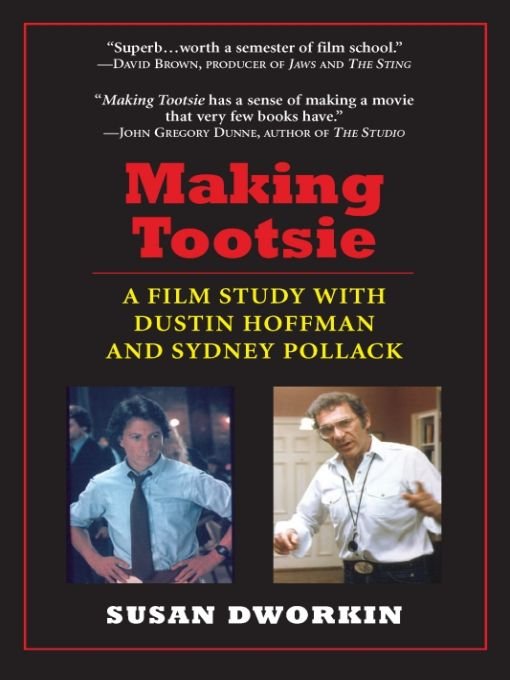

FOR MAKING TOOTSIE BY SUSAN DWORKIN

Rarely do we have that complex creative process revealed to us with such sensitivity and insight.Susan Dworkins Making Tootsie is an important study, in a class with Lillian Rosss Picture and John Gregory Dunnes The Studio. Everyone who seriously cares about movies has to read it.Digby Diehl, Los Angeles Herald Examiner

I once said that wanting to be a screenwriter was like wanting to be a co-pilot. Ms. Dworkin captures that perfectly.Making Tootsie has a sense of making a movie which very few books have.

John Gregory Dunne

A perceptive and provocative work.Dworkin cuts through the film-making process technical lingo and yet managers to maintain a respect for the dynamics that result in a successful film.

Lee Grant, Los Angeles Times

Making Tootsie goes beyond flash to detail the facts behind the project. In so doing, it offers an object lesson in moving making in general.USA Today

A stunning job of research, observation and reporting.

Larry Gelbart, co-writer of Tootsie

and writer on M*A*S*H TV series

Informative, crisply written and worthwhile an intelligent account of the production of the hit movie (and) a remarkably full portrait of Hoffman the actor.

Washington Post Book World

Superb worth a semester of film school. I recommend it to film students and filmgoers, and thats just about everybody.

David Brown, producer of Jaws and The Sting

An enlightening, entertaining study of the evolution of a film.

ALA Booklist

Tootsie has already achieved a reputation as a classic film comedy. Dworkins fluid, marvelously detailed book goes a long way toward explaining why.

People

A solid piece of journalism, compact and lean, by an author who doesnt confuse incident for action, who tells her story without padding.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

The author wishes to acknowledge with gratitude the help of her editor, Bette Alexander, and her publisher, Esther Margolis, in preparing the manuscript, as well as Lucy OBrien and Grace Kubrin who typed and retyped it. Thanks are due to all those from the company and crew of Tootsie who shared their thoughts and gave their time to this book. And a special debt is owed to Rocky Lang for his generous assistance and to Ann Guerin, for her support and wise counsel.

The whole trick with Tootsie was to get Dustin Hoffman to look like a real woman, so that the characters around him in the movie could believe he was a woman and not appear ridiculous for doing so. In Hoffmans contract, there was actually a clause stipulating that reality had to be achieved before shooting could begin.

This meant that Tootsie differed in comic intent from Some Like It Hot, the Billy Wilder classic in which Marilyn Monroe and Joe E. Brown had so engagingly been duped by two hairy girls, Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon. Hoffman would not be hairy. His muscles wouldnt show. Nor would his Adams apple. A vibrant, wiry man with burning brown eyes and the nervous energy of a prizefighter, he intended to bury himself in Tootsie, to disappear into her disguises.

Tootsie joined a cluster of gender-switch comedies that included La Cage Aux Folles I and II, Victor, Victoria and The World According to Garp, which featured John Lithgows transsexual Roberta. (When Tootsie began shooting in April 1982, Barbra Streisands Yentl was still in preparation.)

The theatre, which always has a way of being first, had begun the recent trend two years earlier with Caryl Churchills Cloud 9, directed by Tommy Tune. In this send-up of both sexism and imperialism, men played Victorian matrons, women played Victorian boys, and white men played black men as well as little girls in contemporary London. In The Singular Life of Albert Nobbs, by Simone Benmussa, Glenn Close played a woman who spent her entire adult life impersonating an Irish waiter. This play was on at the Manhattan Theatre Club uptown while Tootsie was shooting in New York, and Hoffman questioned any colleague who went to see it about the details of Closes highly realistic performance.

Although filming lasted 98 days, Hoffman, now 45, invested almost four years of his life in Tootsie, a Columbia Pictures comedy about a down-and-out actor who gets his big break by impersonating an actress. Four years is a long time for a star performer to voluntarily absent himself from the screenall the more so since Hoffmans last performance in Kramer vs. Kramer had won him an Academy Award and a secure reputation as one of our finest actors.

His willingness to devote so much time to Tootsie stemmed from his interest in taking that range of journeys which justifies the madness and hassle of the acting profession. In The Graduate, his hilarious portrayal of a young man seduced by an older woman won him an Oscar nomination. He was nominated again when he played the seedy derelict Ratzo Rizzo in Midnight Cowboy and again for his portrayal of the doomed comedian Lenny Bruce in Lenny. Range was Hoffmans passion. In Papillon he played a French counterfeiter; in All the Presidents Men, an indefatigable journalist; in Straw Dogs, an avenging intellectual. His desire to play a woman in Tootsie may have appeared political in the context of the times, but in fact, it was overwhelmingly artistic. Hoffman was not looking for the truth about women. He was looking for the woman in himself.

The man who finally directed and produced Tootsie was Sydney Pollack. Pollack had not worked with Hoffman before, nor had he ever directed an out-and-out bare-faced comedy. His forte was grown-up, rational romance. His hallmark was melancholy. There were deep creases in his face. A tall, 48 year old man with curly, greying hair and large, expressive hands, he was known in the trade as a lion-tamer, because of his excellent track record in handling big stars like Barbra Streisand (The Way We Were), Robert Redford (This Property is Condemned, Jeremiah Johnson, The Way We Were, Three Days of the Condor, The Electric Horseman), Paul Newman and Sally Field (Absence of Malice), Faye Dunaway (Three Days of the Condor), Jane Fonda (They Shoot Horses, Dont They?, The Electric Horseman) and Al Pacino (Bobby Deerfield). He was trusted by Columbia Pictures because of his extraordinary success at bringing in Absence of Malice $1 million under budget (a Hollywood rarity) and because six of his eight last movies had made money.

From the earliest make-up tests in Los Angeles, all through the arduous shoot in the dead heat of a New York summer, Sydney Pollack and Dustin Hoffman never gave Tootsie a rest. They never gave each other a rest. To keep themselves going, they ate like lab animals. Sydney stopped smoking. He went on the Pritikin diet and took a substantial segment of the company with him. Long after many others had reverted to red meat, he was still incessantly chewing celery and gum and peaches.