MOJO HAND

THE LIFE AND MUSIC OF

LIGHTNIN HOPKINS

TIMOTHY J. OBRIEN AND DAVID ENSMINGER

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS PRESS

AUSTIN

Cop yright 2013 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, 2013

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to: Permissions

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

utpress.utexas.edu/about/book-permissions

Design by Lindsay Starr

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

OBrien, Timothy J. (Timothy Joseph), 19622011.

Mojo hand : the life and music of Lightnin Hopkins / by Timothy J. OBrien and David Ensminger. 1st edition.

pages cm (Brad and Michele Moore Roots Music Series)

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-292-74515-5 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Hopkins, Lightnin, 19121982. 2. Blues musiciansUnited StatesBiography. I. Ensminger, David A. II. Title.

ML420.H6357O27 2013

781.643092dc23

[B]

2012031552

doi:10.7560/745155

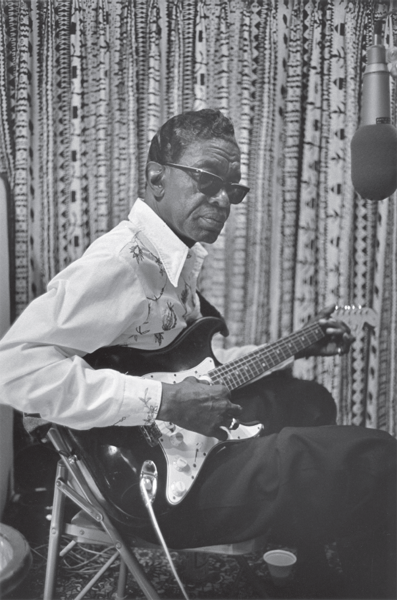

: Lightnin Hopkins, 1972. Photo by Philip Melnick.

ISBN 978-0-292-74516-2 (e-book)

ISBN 978-0-292-75302-0 (individual e-book)

Dedicated to

Kyong Mi OBrien and Yuna OBrien

C ONTENTS

Tim OBrien, Houston, Texas, April 2011. Photo by David Ensminger.

PREFACE

MAKING MOJO

How Two Hearts Can Beat As One

OVER A BOISTEROUS DECADE, Tim OBrien and I attended the same gritty rock n roll shows, wrote high-energy music reviews and previews for papers like the Houston Press, and navigated academia, where we attempted to bridge our concerns for social justice with pop culture and an intensely felt sense of living history. OBrien pursued an exemplary focus on African American Studies and the blues, while I leaned toward examining punk rock cultures democratic impulses and multiculturalism. As a tough-minded, redheaded, fiery-tempered researcher of Irish descent, he could enumerate issues with rapid-fire aplomb, stitching together elements ranging from labor history and death penalty abolition to affordable urban housing, historic preservation, and fair trade movements. I would sit on his couch, simply trying to match the rigor of his thoughts, though I admit his sheer gusto often overwhelmed me.

For decades, when not pressing his ear to the feedback-drenched gyration of garage rock bands like the Dictators and Guitar Wolf, both bands whom he had befriended, he had immersed himself in the blues, especially at clubs like Antones in Austin, Texas, and Fitzgeralds and The Continental in Houston, where he snapped eager photos of wise older players and young turks who filtered the past into their raucous sets with charm and panache, skill and fervor. He contributed articles about them to local papers and submitted entries on Sun Ra, Chuck Berry, and Art Blakey to the Encyclopedia of African American History.

He eyed Lightnin Hopkins endearingly, knowing this unparalleled bluesman had not been researched and scrutinized fully. This robust Texas legend soon became the subject of his dissertation, approved by Dr. William Ferris, professor of history at the University of North Carolina, and Dr. Douglas Henry Daniels, professor of African American history and jazz at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Upon completion, that work soon morphed into this book. OBrien was compelled, seemingly deep in his DNA, to capture Hopkinss often raw-boned, sizzling, and incantatory oeuvre. OBrien also understood that Hopkinss tunes effortlessly fused inveterate woe, fecund joy, and nuanced sociohistorical observations. And OBrien collected at length.

Mining 135 secondary sources, he combed archives with eagerness and delved into Library of Congress collections, record company files in Berkeley, California, privately held collections, census and social security records, and probate court and police records. He unearthed elusive informants deep in Houston and logged endless hours tracking down musicians on the road who were willing to share their stories, eventually conducting 130 oral interviews.

OBrien was no arcane musicologist. He wanted to create and carve out a concisely woven, close-to-the-ground, insightful, and heavily detailed social and cultural history of Hopkins. Together, we edited his dissertation, wrote query letters to publishers, and began assembling this version. We intended the book not merely to appeal to a core audience of musical enthusiasts and others piqued by the texts links to Southern, African American, and American studies, but also to include cultural history readers. We believed the text would appeal to those interested in folklore, performance, and urban studies, and to social justice audiences as well.

Other recent work has also focused on the legacy of Hopkins, such as Lightnin Hopkins: His Life and Blues by Alan Govenar. I believe OBriens primary research tends to be much more wide-ranging and inclusive, including the commentary of Grammy winner Dave Alvin and twice-Grammy-nominated Peter Case, well-admired Americana artists. Whereas Govenar might be considered more poetic and romantic, OBrien aimed for historic depth and breadth. He desired to expose the modern ripples of the subject, tracing how current artists explore the usable past of the blues to address their own artistic concerns and themes.

The book debunks several myths. For instance, Hopkins did not refuse song royalties and record only for cash payments. It also illustrates and explains his idiosyncratic business practices, such as shunning professional bookers, managers, and publicists. We discuss recording sessions at length and also elucidate his lyrics, which embody a keen sense of poetry that transforms mundane aspects of life, from beans to telephones, into vibrant tropes. His diverse song content far exceeds rudimentary blues themes; he readily grasped issues of the day, such as space exploration, the Vietnam War, and lesbianism. In addition to surveying rock n roll guitar players such as Jimi Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughan, the narrative recounts Hopkinss influence on Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Tom Waits, and Bob Dylan, who based his tune Leopard Skin Pillbox Hat on a Hopkins song.

Next page