Copyright 2007 by Monte Irvin and Phil Pepe

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher, Triumph Books, 542 South Dearborn Street, Suite 750, Chicago, Illinois 60605.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Irvin, Monte, 1919

Few and chosen : defining Negro leagues greatness / Monte Irvin with Phil Pepe.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-1-57243-855-2 (alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-57243-855-X (alk. paper)

1. Negro leaguesHistory. 2. BaseballUnited StatesHistory. 3. African American baseball playersHistory. 4. Discrimination in sportsUnited StatesHistory. I. Pepe, Phil. II. Title.

GV875.N35I79 2007

796.357408996073dc22

2006032037

This book is available in quantity at special discounts for your group or organization. For further information, contact:

Triumph Books

542 South Dearborn Street

Suite 750

Chicago, Illinois 60605

(312) 939-3330

Fax (312) 663-3557

Printed in U.S.A.

ISBN: 978-1-57243-855-2

Design by Nick Panos; page production by Patricia Frey

All photos courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York, unless otherwise indicated

Monte Irvins Hall of Fame induction speech on pages xxviixxviii is reprinted with permission of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library. Branch Rickeys remarks on pages 3638 appeared in Baseball Has Done It, copyright by Jack R. Robinson and Charles Dexter and published by J.B. Lippincott Company in 1964. Publisher has made every effort to obtain permission to reprint this piece.

This book is affectionately and gratefully dedicated to all those who blazed the trail in the Negro Leagues but never got the chance to display their enormous talents on the national stagethe major leaguesplayers like Pop Lloyd, Biz Mackey, Josh Gibson, Smokey Joe Williams, Buck Leonard, Leon Day, Willie Wells, Oscar Charleston, Cool Papa Bell, Ray Dandridge, Double Duty Radcliffe, and dozens of others.

It is also dedicated to those who had the courage and the foresight to make it finally happen

To Jackie Robinson, Branch Rickey, Clyde Sukeforth, Commissioner A.B. Happy Chandler, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, Commissioner Fay Vincent, Bob Feller, and Ted Williams, who first called for the inclusion of Negro Leagues players in the Hall of Fame during his induction speech in 1966.

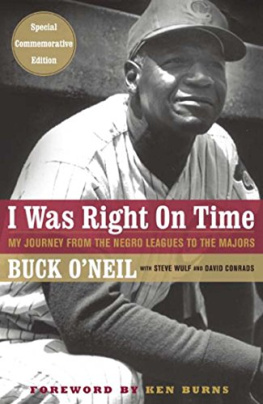

And finally, it is written in loving memory of John Jordan Buck ONeil (19112006).

Dedicated to Negro League Baseball

(Oh how)

I wish I couldve seen

My brothers play ball

With

That ole negro league

I mean

To really get down

On that coppered colored diamond

And

Pitch a no-hitter

With Flamin Satchel or Slim Jones

To see a whole crowd

Of Colored folk

A jumpin and a hollerin

Holding dey babies

With men grittin

Ivory stained cigar teeth gambling

(screaming)

Popcorn!!!

Peanuts!!!

Admission?

Boy

Dont you know its free to see

Buck ONeils watchful eye on the plate

Buggin it

Right out of the park

Or

Leon Days smile speckle sunshine

On a gray and cloudy afternoon.

Remember that?

Reckon not.

But I wish

I couldve seen

My brothers

PLAY BALL!

Stewart Lee Stone

Stewart Lee Stone of Lexington, Kentucky, a recent graduate of Berea (Kentucky) College, was born some 30 years after the Negro Leagues folded. As a youngster, he developed an interest in African American culture and became fascinated with Negro Leagues baseball after reading a childrens book on the subject.

His poem, Dedicated to Negro League Baseball, was written when he was 17 years old and earned him the prestigious 2005 Francis S. Hutchins Award from Berea College.

Contents

Index

Preface

I t had to have been a holiday. If April 10, 1947, was a Thursday and there was no school (I never would dare play hooky), it must have been the Easter recess. What I do remember is that it was three weeks past my 12th birthday, and my brother Paul, two and a half years my senior, and I took advantage of the break in school to go to a baseball game.

It was only an exhibition game, the Dodgers against their Triple A International League farm team, the Montreal Royals, but any chance to see our beloved Dodgers was a treat.

Armed with a bagful of Moms sandwiches, we made the 45-minute journey by train, walked past Prospect Park and the Botanical Garden, past the Bond Bread sign, and arrived at Ebbets Field where we purchased our customary bleacher seats, 60 each.

I have no recollection of what happened in the game, who won, or whether there were any home runs or any sensational catches.

One thing I recall is that even from as far away as the bleachers, it was apparent that the only black player on either team was a Montreal infielder named Jackie Robinson. I was not enlightened enough to comprehend the historical significance of that, or of the report in the next days newspaper that the Dodgers had purchased the contract of that same Jackie Robinson and that he would be in their starting lineup against the Boston Braves for the season opener five days later.

In the early days of the new season, I closely monitoredthrough box scores in the newspaper and by listening to games on the radiothe new mans performance. I rooted hard for Jackie Robinson to succeed, not out of any social consciousness, or because I wanted baseball to right its wrongs of the previous 50 years, or in the spirit of equality and fair play, or because I was aware of the enormous pressure he was under and the threats he endured to his physical well-being, or because of the bigoted verbal attacks he faced from opposing players and even from some of his teammates who protested his presence and threatened to boycott the team rather than play alongside him. At 12 years old, what did I know about racial injustice? My reason for rooting for Robinson was a basic and selfish one. He was a Dodger, and I wanted him to do well, to hit and field and run and help my Dodgers win their first pennant in six years.

In my neighborhood, we rarely saw a black person. There was one man who worked on a coal truck, and he came to deliver coal to the houses on my street.

In the eighth grade I had a black classmate. His name was Paul Williams, and he lived about 10 blocks away from me. We werent very close. I never invited him to my home, and I was never invited to his, but he played third base on my sandlot baseball team, and we were happy to have him because he was a good player.

The adults in my neighborhood were divided into those who were anti-Robinson and those who were pro-Robinson. Those who were Dodgers fans rooted for Robinson; those who were fans of other teams rooted against him, even one in my own household. My father wanted Robinson to fail, because my father was a Giants fan. When the Giants acquired Henry Thompson, Willie Mays, and Monte Irvin, Dad rooted hard for them. Monte Irvin was my fathers favorite player.

Next page