Contents

Landmarks

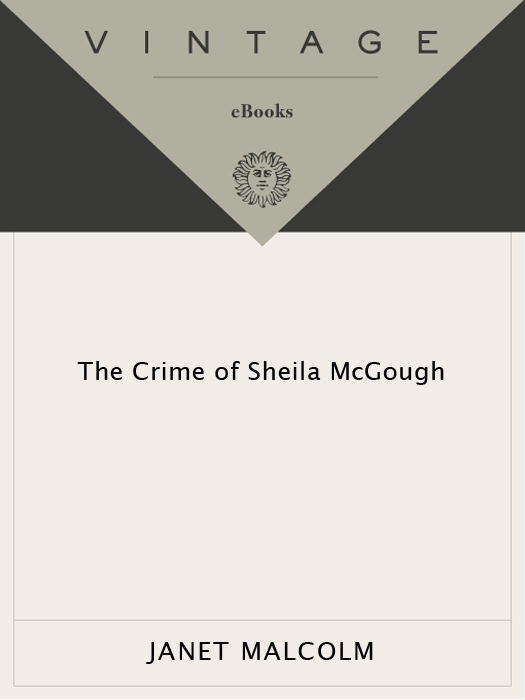

Copyright1999 by Janet Malcolm

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, in 1999.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition as follows:

Malcolm, Janet.

The crime of Sheila McGough / by Janet Malcolm.

p. cm.

1. McGough, SheilaTrials, litigation, etc. 2. Trials (Fraud)Virginia

Alexandria. 3. Criminal justice, Administration of.

I. Title.

KF224.M357M35 1999

345.730263dc21 98-48635

eISBN: 978-0-307-83057-9

www.vintagebooks.com

rh_3.1_c0_r3

Contents

Acclaim for JANET MALCOLM s

THE CRIME OF

SHEILA

McGOUGH

It is wonderful to see Malcolm turn her full attention to a criminal proceeding. [N]o other writer tells better stories about the perpetual, the unwinnable, battle between narrative and truth.

The New York Times Book Review

[A] curious and disturbing tale an intensely personal and critical examination of law in contemporary America. [Malcolm] has the passion of a natural reformer, a messianic zeal strangely, yet often brilliantly, channeled into language.

Joyce Carol Oates, The New York Review of Books

A beautifully written and tautly argued meditation-provocation on the law.

The New York Observer

Uncommonly interesting. This intriguing book is not entirely McGoughs story it is just as much the story of Malcolms pursuit of the story, and it makes for exceptionally good reading.

Chicago Tribune

Stunning. [A] rumination on the conflict between truth and narrative injected with a dry, biting wit.

New York Post

[An] unconventional, unforgettable book about the netherworld of the U.S. judicial system.

The Denver Post

[A] fascinating tale, and Malcolm, with her clear thinking and constant self-questioning, combs neatly through the tangled strands, ruminating here and there on the intricacies and obfuscations of the law.

Salon

Malcolm capitalizes on the journalists freedom and the rules of evidence to draw the reader irresistibly into the story of an attorney who became a felon.

The Womens Review of Books

Malcolms penetrating books derive their power not only from her great command of language and fascination with the tricky stories she shrewdly explicates but also from her unceasing inquiry into the morality and drama of journalism itself.

Booklist

JANET MALCOLM

THE CRIME OF

SHEILA

McGOUGH

Janet Malcolms previous books are Diana and Nikon: Essays on Photography; Psychoanalysis: The Impossible Profession; In the Freud Archives; The Journalist and the Murderer; The Purloined Clinic: Selected Writings; and The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes. She died in 2021.

ALSO BY JANET MALCOLM

Diana and Nikon: Essays on Photography

Psychoanalysis: The Impossible Profession

In the Freud Archives

The Journalist and the Murderer

The Purloined Clinic

The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes

To Gardner

He didnt answer. He rather said: It is possible to think this: without a reference point there is meaninglessness. But I wish youd understand that without a reference point youre in the real.

S HARON C AMERON,

Beautiful Work: A Meditation

on Pain |

PART I

T HE TRANSCRIPTS of trials at laweven of routine criminal prosecutions and tiresome civil disputesare exciting to read. They record contests of wit and will that have the stylized structure and dire aura of duels before dawn. The reader feels as if he has been brought to the clearing and can smell the wet grass; at the end, as the sky begins to show more light and the doctor is stanching a wound, he takes away a sense of having attended a momentous, if brutal and inconclusive, occasion.

Trial transcripts have no author, but they read as if someone wrote them. Their plot revolves around two struggles. One struggle is between two competing narratives for the prize of the jurys vote. The other is the struggle of narrative itself against the constraints of the rules of evidence, which seek to arrest its flow and blunt its force. The word objection appears in the transcript perhaps more frequently than any other, and betokens the story-spoiling function of the law. The law is the guardian of the ideal of unmediated truth, truth stripped bare of the ornament of narration; the judge, its representative, adjudicates between each lawyers attempt to use the rules of evidence to dismantle the story of the other, while preserving the integrity of his own. The story that can best withstand the attrition of the rules of evidence is the story that wins.

The laws demand that witnesses speak nothing but the truth is a demand no witness can fulfill, of course, even with Gods help. It runs counter to the law of language, which proscribes unregulated truth-telling and requires that our utterances tell coherent, and thus never merely true, stories. This lawwith its servants ellipsis, condensation, presupposition, syllogismmakes human communication possible. It also provides trial lawyers with endless opportunities for discrediting opposing witnesses. In the discourse of real lifelife outside the courtroomthe line between narration and lying is a pretty clear one. As we talk to each other, we constantly make little adjustments to the cut of the truth in order to comply with our listeners expectation that we will guide them to the point of what we are saying. If we spoke the whole truth, which has no pointwhich is, in fact, shiningly innocent of a pointwe would quickly lose our listeners attention. The person who insists on speaking the whole truth, who painfully spells out every last detail of an action and interrupts his wife to say it was Tuesday, not Wednesday, and the gunman was wearing a Borsalino, not a fedora, is not honored for his honesty but is shunned for his tiresomeness. In a courtroom, however, he would be one of the few people who could withstand cross-examination, who would not be caught in the web of one or another of the small untruths most of us mechanically tell in order that human communication be a swift, clear river rather than a sluggish, obstructed stream.

As I was rereading the transcript of a criminal trial held in federal court in Alexandria, Virginia, in the fall of 1990, my attention was caught by an example of one such narrativizing untruth uttered by a prosecution witness named Frank Manfredi, as he was being questioned by the prosecutor, Mark J. Hulkower. Hulkower was eliciting from Manfredi the history of a business transaction that lay at the heart of his case against the defendant, a forty-eight-year-old lawyer named Sheila McGough. The exchange between Hulkower and Manfredi went as follows:

Q: Directing your attention to May 1986, did you have occasion at that time to become involved in a transaction for the purchase of insurance companies?