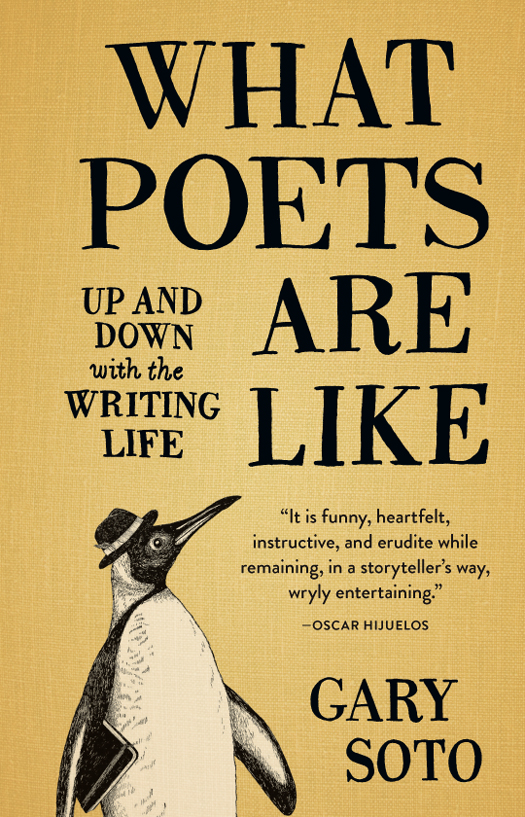

Copyright 2013 by Gary Soto

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by Sasquatch Books

Editor: Gary Luke

Project editor: Michelle Hope Anderson

Design: Anna Goldstein

Cover illustration: Frida Clements

Copy editor: Michael Townley

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication

Data is available.

eISBN: 978-1-57061-875-8

Sasquatch Books

1904 Third Avenue, Suite 710

Seattle, WA 98101

(206) 467-4300

www.sasquatchbooks.com

v3.1

To Loving Carolyn

Who Has Seen It All

Contents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

SEVERAL OF THESE PIECES appeared in the literary magazines Huizache, the Threepenny Review, and Zyzzyva.

Though We Started Out New, Dont Do It, and Fable of the Lost Poets were published as the chapbook The Three of Us by Aureole Press at the University of Toledo. The fine-press printer was Tim Geiger.

The Wind Sends Small Creatures and At Rest, Laborers Lean on Me appeared in The Word Exchange: Anglo-Saxon Poems in Translation (W. W. Norton & Company, 2011), edited by Greg Delanty and Michael Matto.

The poet greatly appreciates Peter Fong, Gary Luke, and Carolyn Soto for editorial suggestions.

PREFACE

AGING POETS ARE LIKE cartons of milk just days away from expiration, when they become the curdled contents ready to be poured down the drain. This is what a poet friend of mine reflected at the end of the school year. I argued, No, old verbal prankster, not every poetIm a slender quart of skim milk while you, Im afraid, are a squat carton of half-and-half. We love this kind of banter though we remain best of friends. Still, he might be right on one score: age does tend to make one sour. He occasionally goes off on this train of thought with a proper drink in his paw, reminiscing Oh, those poems, those publications, those nearly grasped pearly prizes and honors, those bookstore readings, those fellowships that allowed us to travel. Those bookstore readings? I recall more empty chairs than occupants, and some in those chairs were just resting before they shoved off to the magazine section.

That theres more hair circling our ears than on top of our heads is a concern. A headier worry is that many of our best poems have already been written and now lay in the past. What poems do we have left in us? I have thirteen books of poetry for adults along with seven for young readers. I began writing poetry at age twenty while a junior college student, with a vague notion of what a poem was and what a poem should do emotionally. How did I start? By discovering Edward Fields poem Unwanted, in which a meek man desperately seeks recognition, even if it means hanging his photo on a bulletin board in the post office. As a teen, the speaker in the poem had been bullied and ignored. He suffered slursdumbbell, good-for-nothing, jewboy sissy. Now in his mid-thirties, his once curly hair is fuzzy. He has no physique. His eyesight has diminished. In short, he is the archetype of a pushover. But he has one meaningful attribute: he responds to love. If you call him, he, like a happy dog, will come. How I leaked a tear or two and said in my heart, Mr. Field, you are recognized.

Though I discovered poetry in 1972, I had the emotional stirrings of a poet earlier onmuch earlier, at age four, when I had sympathy for a bean plant that had to live with its tiny arms outstretched, as if being punished, like Jesus on the cross. I didnt have much in the way of toys, so pinto beans served as my army men. They worked nicely as I moved them across the sandy ground of our house on Braly Street. One morning I discovered that a bean plant suddenly had emerged, unraveling to its full height. I was awed by its appearance and then bewildered when within days the arms of the plant began to lower, dehydrated. Then another bean plant appeared, and then others, all of them first lifting their arms and then lowering them, their lung-shaped leaves wilting under the Fresno heat. At age four I grasped the circle of life.

These prose pieces have the mystery of poetrybrief, imagistic, true, reflective, and individually mine. I write about like-minded souls, seventeenth-century diarist Samuel Pepys, for instance, and offer light moments such as the time I rubbed shoulders with Hayley Mills, child star of the early 1960s. I write about London and Fresno, and Berkeley, where I have lived for thirty-five years. Im a scoundrel on some pages and a noble on others. I write about poet friendsChristopher Buckley, Jon Veinberg, Gary Youngand another amigo, David Ruenzel. My wife of thirty-eight years is with me in these pages. My arms that once lifted skyward are now at my side, exhausted.

Im a poet, though possibly better dressed than most of them, as readers will discover in The Winning Crowd. Im greedy, generous, jealous, occasionally drunk, educated in a quirky way, overlooked, witty, and team member not. I live by my five senses, particularly tasteGod, I love that winecan I get it for under ten bucks?

Ive been writing poetry for forty yearsthis is what I do. I pulled Fames longish hair and discovered her wearing a wigthe locks came off in my hand. Im troubled, then not troubled. I believe in the greatness of Pablo Neruda. I believe in ignored artists, such as DeLoss McGraw. I appreciate gardens, literary history, and novels that I can read in three days. My favorite color is yellow, though for years I thought it was blue. I support California Rural Legal Assistance. My heroes are members of the Lincoln Brigade. The 442nd Regimental Combat Team also means something to me. Cesar Chavez is a flag in my heart. My daughter Mariko is smarter than I. I love my wife. My cat adores me from any distance.

Im a poet who feels like all the othersmostly ignored. I work best in the morning. My mail arrives in late afternoon. Dogs appear frequently in my poems. I respond to love. If you call me, I will get up from my chair, a little slower now that Im a senior, and come to you.

AGING POET

I CANCELLED MY LOVE FOR THE DOG when he yawned while I was reciting a poem. He yawned a second time before I got to the really good part, rose stiffly from his rug, and squeezed his bulk through the cat door. This departure demonstrated his dislike of poetry. Or was it only my poetry? Was I losing it? Still, I wasnt about to give up on poetryor on the white-haired muse who, after my thirty-seven-year career, no longer appears to have much bite. (I can imagine her depositing her teeth in a jar, just before sleep.) At the fruit bowl, I lifted a fig, pierced it with my fingers, then ate it with my eyes closed. It was the best sex Id had in months. I was enjoying a second, drier fig when a tomcat slinked by the window, feathers from a hot meal still in his mouth. I know this cat. The furry beast has deflowered many a young cat and fathered many a kitten. He eats birds with a toothy fervor, until only the heads and feet are left.

The late afternoon fell, another inky thumbprint at the edge of my poem. The dog returned through the cat door. It was my fault. Id had him neutered when he was a lollygagging pup. Now old, he holds a tennis ball in his mouth, waiting for someone to play with.