L IFE W RITING S ERIES

In the Life Writing Series, Wilfrid Laurier University Press publishes life writing and new life-writing criticism and theory in order to promote autobiographical accounts, diaries, letters, memoirs and testimonials written and/or told by women and men whose political, literary, or philosophical purposes are central to their lives. The Series features accounts written in English, or translated into English from French or the languages of the First Nations, or any of the languages of immigration to Canada.

The audience for the series includes scholars, youth, and avid general readers both in Canada and abroad. The Series hopes to continue its work as a leading publisher of life writing of all kinds, as an imprint that aims for scholarly excellence and representing lived experience as tools for both historical and autobiographical research.

We publish original life writing which represents the widest range of experiences of lives lived with integrity. Life Writing also publishes original theoretical investigations about life writing, as long as they are not limited to one author or text.

Series Editor

Marlene Kadar

Humanities, York University

Manuscripts to be sent to

Lisa Quinn, Acquisitions Editor

Wilfrid Laurier University Press

75 University Avenue West

Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3C5, Canada

Wilfrid Laurier University Press acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities. This work was supported by the Research Support Fund.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

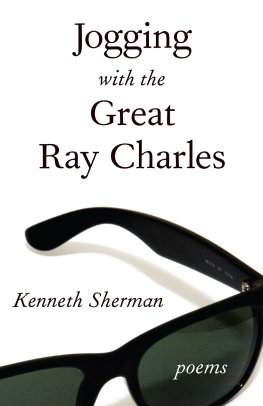

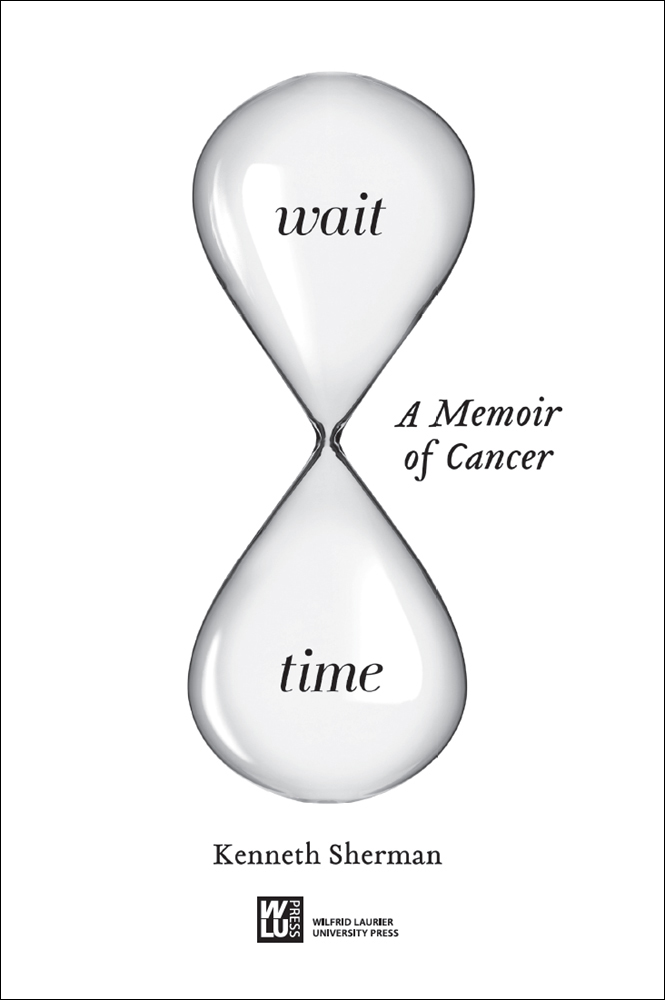

Sherman, Kenneth, 1950, author

Wait time / Kenneth Sherman.

(Life writing)

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77112-188-0 (paperback).ISBN 978-1-77112-189-7 (pdf).

ISBN 978-1-77112-190-3 (epub)

1. Sherman, Kenneth, 1950 Health. 2. CancerPatientsCanadaBiography. 3. Poets, Canadian (English)20th centuryBiography. I. Title. II. Series: Life writing series

PS8587.H3863Z53 2016 | C811.54 | C2015-905583-0 |

C2015-905584-9 |

Cover design by Sandra Friesen. Cover image by Ziviani, hourglass, iStock photo. Text design by Mike Bechthold.

2016 Wilfrid Laurier University Press

Waterloo, Ontario, Canada

www.wlupress.wlu.ca

This book is printed on FSC certified paper and is certified Ecologo. It contains post-consumer fibre, is processed chlorine free, and is manufactured using biogas energy.

Printed in Canada

Every reasonable effort has been made to acquire permission for copyright material used in this text, and to acknowledge all such indebtedness accurately. Any errors and omissions called to the publishers attention will be corrected in future printings.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit http://www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Sickness sensitizes man for observation, like a photographic plate.

Edmond and Jules de Goncourt (Journals, 1865)

There is, let us confess it (and illness is the great confessional), a childish outspokenness in illness; things are said, truths blurted out, which the cautious respectability of health conceals.

Virginia Woolf (On Being Ill, 1926)

The patient has to start by treating his illness not as a disaster, an occasion for depression or panic, but as a narrative, a story.

Anatole Broyard (Intoxicated by My Illness, 1992)

Contents

Foreword

Kenneth Sherman is a writer. But with this publication he is also a subject, a patient. As the subject, he patiently writes from the point of view of timekeeperthe person who measures time in order to call times up should the time limits be exceeded. He keeps time as he waits to find out how ill he is, which treatments he must endure, and ultimately how long he might have to live: What is the rate of OS (overall survival) in his case? What are the time limits?

Shermans endurance is measured by his method of note-taking. The book is metred by a collection of dated entries that begins with his first medical appointment and ends with a brief meditation on time and how it means differently to those whose time has come to enter the world of the healthy.

Waiting to hear from physicians about the state of ones health is both a blessing and a trial by fire. Most of the time we are told not to worry while we wait, which every good, mature human being will try to accomplish; and most of the time the news is good, or neutral, and requires no further expenditure of emotion or pain or waiting.

But sometimes the news is not good. Sometimes it is a diagnosis of cancer, the word that was once only whispered, not even spoken out loud.

Sherman does suffer getting the bad news (finally) that he has kidney cancer and that the cancer has spread to a bone, a single rib. Adjusting to such news is difficult for him, as it would be for anyone; but because Sherman is both a patient and a scholar, he is able to write, with expression and nuance, about his experience, and about the disease and the feelings that accompany it, and about numerous other wise patients who became narrators of illness. He is particularly aware of philosophers whose own diagnoses of cancer provided the fodder for their first-person narrations.

Sherman experiences a sea change of identity as soon as he learns he is a sick man. Before that moment, on March 18, 2010, he is waiting for a diagnosis; after that moment he is waiting for health, ideally to be disease-freewhich is not always possible when cells exchange normalcy for malignancy rapidly and energetically. The institution of Medicine and those who agree to uphold it and apply it are in the arduous position of keeping up with these cells as best they can without always being able to see them, measure them, target them, halt them, kill them. As Sherman says elsewhere, these cells are more vigorous and intelligent than their vanquished brother and sister cells. He refers to Siddhartha Mukherjee, the highly regarded author of The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer, who insists that cancer is a parallel species more adapted to survival than we are (6364).

A change of another sort occurs on March 18, 2010, too. Sherman that day becomes a patient with a potentially death-dealing illness and also a writer who uses his illness to fuel a creative act. Luckily for other patients and readers, Sherman embarks on an extemporization. Once the doctor tells you you are ill, you begin to eke out your existence as a patient. Your life becomes an improvisation around the theme of illness (46). For me, that improvisation is the only saving grace in what other narrators have called their cancer journeya ubiquitous and tedious phrase used to give the personal experience of a cancer a metre, a continuum respecting its development through stages and types. To improvise is to write around the event, an event that does not often have a foreseeable end, and if it is deemed a happy ending by good readers of this book, it is not as comforting as happy endings are meant to be. The ending, of course, is of necessity made up. There is a lull: we have made progress; things are much better; the side effects are nothing when compared to the disease. And yet most patients I know live in the middle of this lull where arguably the main concern is the returnthe return of the same cancer or of another canceror the appearance of a different transformed disease or a new cancer induced by the treatment.

Next page